Sommaire

Introduction

Since the launch of ICANN’s New gTLD Program in 2012, the domain name landscape has undergone a profound transformation. This initiative has enabled the introduction of hundreds of new thematic, geographic, and sector-specific extensions (.shop, .paris, .app, .law, etc.), offering businesses enhanced opportunities for online positioning. However, this diversification has also brought increased risks of cybersquatting and brand infringement, compelling rights holders to adapt their protection strategies.

The Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) remains the central, globally recognised mechanism for resolving disputes over domain names registered in bad faith, whether they involve legacy extensions (.com, .net) or the new gTLDs. Today, the UDRP must address a rising volume of disputes and increasingly varied contexts, requiring more tailored approaches.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of developments since the landmark Canyon.bike case in 2014, examines recent trends in UDRP disputes involving new extensions, and outlines strategic recommendations for trademark owners in 2025.

Context and scope of the UDRP for new extensions

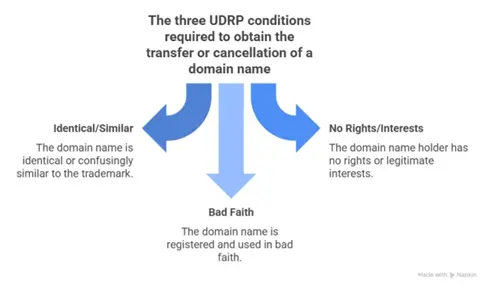

Adopted by ICANN in 1999, the UDRP applies to all generic top-level domains (gTLDs), whether they are legacy extensions or part of the New gTLD Program. It allows a trademark owner to obtain the transfer or cancellation of a domain name where three cumulative conditions are met:

- The domain name is identical or confusingly similar to the trademark;

- The domain name holder has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name;

- The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

This framework applies to all new extensions, thereby ensuring legal consistency on a global scale.

Evolution of new extensions since 2014

Growth and diversification of gTLDs

Since 2014, the number of available extensions has increased dramatically, now exceeding 1,200 delegated gTLDs. These fall into several categories:

- Thematic extensions (.shop, .tech, .app) targeting specific industries;

- Geographic extensions (.paris, .london) highlighting local presence;

- Community or specialised extensions (.law, .bank), often subject to strict eligibility requirements.

Trends and most-used extensions

Some new extensions have quickly gained prominence due to their universal appeal and marketing potential, such as .xyz, .online, and .shop. These have also become prime targets for cybersquatters, necessitating enhanced monitoring measures.

Case law and landmark decisions

The Canyon.bike case (2014)

This decision remains the first known UDRP case involving a new extension. It confirmed that the extension itself does not influence the assessment of similarity between the trademark and the domain name: the decisive element is the string to the left of the dot.

Recent jurisprudential developments

Since 2014, numerous cases have involved new extensions. UDRP panels apply the same criteria to recent gTLDs as to legacy ones, while considering the specific context of certain extensions, particularly when the extension reinforces the association with the trademark’s industry sector. Decisions also show heightened vigilance toward multiple registrations across different extensions targeting the same brand.

Issues and strategies for trademark owners

Monitoring and anticipation

The proliferation of extensions makes it essential to implement automated and targeted monitoring of trademark terms across all relevant extensions.

Selecting the appropriate procedures

Depending on the case, several options are available:

- UDRP: to obtain permanent transfer or cancellation;

- URS (Uniform Rapid Suspension): for clear-cut cases of cybersquatting, enabling swift suspension;

- Local procedures: such as Syreli for .fr, when the domain name falls under a ccTLD.

Building strong cases

The success of a complaint hinges on demonstrating all three UDRP criteria with clear, tangible evidence of the trademark’s reputation and the respondent’s bad faith (e.g., multiple registrations, deceptive use, redirection to competitor websites).

Conclusion

New extensions offer businesses unprecedented opportunities for online visibility but also open new fronts for rights infringements. The UDRP remains as relevant and effective as ever, provided it is integrated into a comprehensive strategy combining monitoring, rapid action, and careful selection of dispute resolution procedures.

Dreyfus & Associés assists clients in protecting and defending their rights across all extensions, in partnership with a global network of intellectual property law specialists.

Nathalie Dreyfus, with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

What is a new gTLD?

A generic top-level domain introduced after 2012, such as .shop, .paris, or .app, expanding the range of available domain name choices.

Does the UDRP apply to new extensions?

Yes. It covers all ICANN-approved gTLDs, whether legacy or new.

Should all extensions be monitored?

It is advisable to target the extensions most relevant to your sector and market to optimise monitoring costs and effectiveness.

Can multiple domain names be challenged in a single procedure?

Yes, if they are registered to the same holder and circumstances justify joint action.

How can a respondent’s bad faith be proven?

Through evidence such as the trademark’s reputation, redirection to a competitor’s site, or offering the domain for sale at an excessive price.