Sommaire

Introduction

An M&A deal is often decided on an element that is mistakenly viewed as “technical” until the documentation is scrutinized: the trademark. Where ownership is clear, registers are properly updated and use is consistent, the trademark supports a significant portion of the valuation, reduces legal uncertainty and facilitates post-acquisition implementation.

Conversely, an unclear chain of title, rights scattered across territories, or a trademark that is challenged or vulnerable (cancellation or revocation) may lead to price renegotiation, reinforced protections, or even the termination of the transaction.

Why trademarks are a decisive asset in M&A?

A trademark is not merely a graphic sign: it is an enforceable right…or a fragile advantage

A trademark is an asset because it grants an exclusive right to use a sign for designated goods and services. It enables the owner to prevent confusing uses, structure a distribution policy, support international expansion and protect marketing investment. However, its value depends on verifiable facts: who owns the trademark, in which territories, for which goods/services, and subject to which contractual constraints?

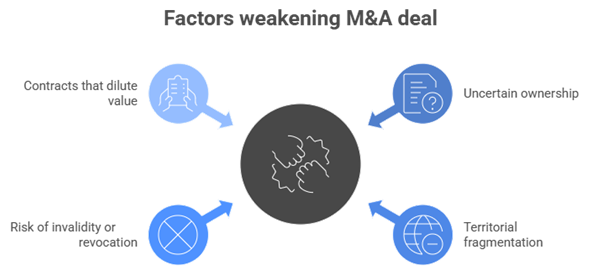

Common situations in which trademarks weaken the transaction

• Uncertain ownership: the seller uses the sign but is not (or is no longer) the recorded proprietor. This undermines enforcement against third parties and complicates transfer. Under French law, recording transfers and changes is a key condition for opposability.

• Territorial fragmentation: the same sign is owned by different entities depending on the country, complicating a global strategy (communications, social media, distribution, parallel imports). This is common in older portfolios or those built through successive acquisitions.

• Risk of invalidity or revocation: descriptive trademark, serious prior rights, insufficient use for certain classes, overly broad specifications disconnected from actual activity, a portfolio that is “theoretical” rather than defensible.

• Contracts that dilute value: exclusive licenses, imbalanced coexistence agreements, security interests, non-challenge commitments, transfer restrictions or change-of-control clauses.

Trademark audit: the checks that protect price and completion

1) Start from the business strategy

First, identify the portfolio’s strategic marks: the main trademark, sub-trademarks, slogans, logos, country-specific marks, flagship product names, and their role in the company’s growth (line extensions, new markets, new channels). The goal is not merely to take stock, but to confirm that the portfolio truly supports the post-acquisition plan (roll-out, expansion, diversification, internationalisation).

2) Secure the chain of title and opposability

Next, the asset must be regularised before being transferred. In France, INPI sets out the recording of events affecting a trademark’s life (assignment, change of name, merger, etc.), which contributes to publicity and opposability.

Key points of attention: in France and in the European Union, an up-to-date register is a condition for a transfer that is fully opposable and practically usable; for international trademarks, changes of ownership are handled through WIPO procedures.

3) Verify the validity of the sign

A portfolio can be extensive and yet fragile. It is therefore necessary to assess the likelihood that a third party could obtain invalidation of the trademark in contentious proceedings, by examining distinctiveness, relevant prior rights and the market context. This assessment is decisive: it determines the ability to defend the trademark, to invest, and to expand the commercial strategy without paralysing disputes.

4) Verify use and the administrative regularity of the titles

A trademark must remain “alive”. This requires checking renewals, the consistency of recorded data (owner, address, goods/services) and the existence of strong evidence of use (packaging, invoices, campaigns, dated screenshots, commercial documents). Portfolios that have undergone multiple restructurings can become difficult to operate if evidence and documentation have not been centralised.

5) Review the contracts

The buyer acquires a right to use and exploit. Change-of-control provisions, exclusivity clauses, territorial limits, quality-approval obligations, or sub-licensing restrictions can reduce value, constrain strategy or trigger renegotiation. A licence misaligned with the post-acquisition strategy may, in practice, neutralise a portion of the valuation.

6) Integrate the digital perimeter

A trademark’s digital footprint is inseparable from the trademark: domain names, marketplaces, social media, content and accounts. On certain platforms, access to trademark-protection tools requires proof of ownership and consistency between the recorded proprietor and the operating entity. Any inconsistency in the register can delay critical actions (content removal, seller blocking, internal trademark-protection processes).

7) Do not overlook data

Where valuation relies on customer relationships, marketing performance and customer files, compliance becomes an economic parameter. CNIL recalls the rules applicable to the sale/transfer of customer databases (information, rights, proportionality, security, etc.).

From the audit report to transaction clauses: securing the transaction without unnecessary over-negotiation

Match each identified risk with an appropriate measure

A weakness in title or a latent dispute does not automatically require abandoning the transaction. However, it must be translated into a clear mechanism: price adjustment, price holdback, escrow, capped indemnity, or a targeted condition precedent (recording an assignment, releasing a security interest, contractual regularisation). The logic is straightforward: a specific risk calls for a specific, proportionate and verifiable response.

Organise pre- and post-completion regularisation while protecting the timetable

Regularisation takes time: recordals, multi-territory signatures, supporting documents and historical corrections. For sellers, putting IP assets “in order” ahead of time reduces negotiation fatigue and strengthens the file’s credibility. For buyers, the audit should be approached as a structuring decision: what must be resolved before completion and what can be treated afterwards, with appropriate protections and a controlled timetable.

Conclusion

In M&A, trademarks can make or break the transaction: they concentrate value, but also potentially decisive weaknesses (opposability, territorial scope, use, contracts, disputes, digital issues). A structured audit and rigorous contractual implementation turn trademarks into a tool for security and negotiation, rather than a late-stage source of uncertainty.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Dreyfus & Associés works in partnership with a global network of attorneys specializing in Intellectual Property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

Q&A

1) What does a trademark audit cover in an M&A transaction?

It involves reviewing ownership, validity, use, contracts and disputes relating to trademarks in order to secure price and completion.

2) What documents should the seller prepare to avoid delays?Up-to-date certificates and register extracts, assignment deeds and evidence of recordal, renewal schedules, evidence of use (invoices, catalogues, packaging, campaigns), contracts (licences, distribution, coexistence, security interests) and any litigation history.

3) What are the most frequent chain-of-title issues?

Trademarks filed in a founder’s name and used by the company without recorded transfer; intra-group transfers not recorded after restructuring; errors in corporate name or address; partially executed assignments; assignments unclear as to scope (territories/classes).

4) How should a trademark owned by different entities across territories be handled?

Through a rights map and a strategy combining additional filings, coexistence agreements, licences, intra-group reorganisation, or a trademark adjustment aligned with commercial priorities.

5) What if the audit reveals a missing recordal or a missing deed?

Implement a regularisation plan (reconstituted deeds, signatures, recordals), typically through a condition precedent or a specific covenant, supplemented where necessary by a holdback or escrow.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance to the public and to highlight certain issues. It is not intended to apply to specific circumstances or to constitute legal advice.