Sommaire

- 1 Introduction

- 2 RDRS: what it is (and what it is not)

- 3 What ICANN’s 30 October 2025 resolution changes in practice?

- 4 What ICANN84 in Dublin revealed: the real friction points

- 5 RDRS vs SSAD: why the distinction matters for strategy and compliance

- 6 European data protection: how GDPR logic shapes disclosure decisions

- 7 Operational implications by stakeholder type

- 8 Conclusion

- 9 Q&A

Introduction

ICANN’s Board decision of 30 October 2025 keeps the Registration Data Request Service (RDRS) running until December 2027, while the community debates whether RDRS should evolve into a long-term, standardised access model (such as SSAD or a successor). The practical consequence is immediate: for the next two years, stakeholders must operate in a “hybrid” environment where disclosure requests are increasingly standardised in format, but still uneven in coverage, timelines, and authentication.

RDRS: what it is (and what it is not)

The Registration Data Request Service (RDRS) is a pilot service launched on 28 November 2023 to standardise the submission format of requests to obtain non-public gTLD registration data from ICANN-accredited registrars. It is intentionally not a final policy framework: it is a “real-world instrument” to measure demand, collect operational metrics, and identify policy gaps, so the community can decide what a durable system (e.g., SSAD) should look like.

What this means concretely: RDRS standardises the front door, not the outcome. Each registrar still applies its own legal assessment and decision-making, within applicable law and ICANN policy.

What ICANN’s 30 October 2025 resolution changes in practice?

ICANN’s Board confirmed that RDRS will continue operating for up to two years beyond the pilot, i.e., until December 2027, while the community works through next steps and policy alignment.

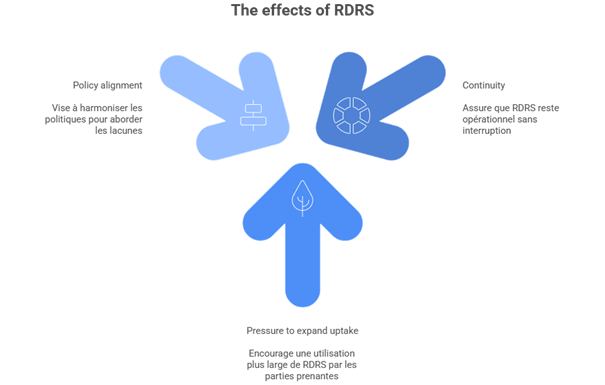

From an operational perspective, three points matter most:

• Continuity: rights-holders and investigators can keep using RDRS as a live channel rather than losing it at the end of the pilot.

• Pressure to expand uptake: the Board explicitly encouraged comprehensive usage by requestors and registrars, without (yet) converting it into a mandatory regime.

• Policy alignment is now the battlefield: ICANN opened a public comment process on the “RDRS Policy Alignment Analysis”, positioning it as the roadmap for addressing gaps (privacy/proxy underlying data, urgent timelines, authentication, etc.).

What ICANN84 in Dublin revealed: the real friction points

ICANN84 (Dublin, 25–30 October 2025) made one reality unavoidable: RDRS is useful, but incomplete, and its weakest points sit exactly where brand protection and law enforcement most need predictability.

Voluntary participation creates structural blind spots

A recurring concern is that participation is not universal. The Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC) highlighted that optional registrar participation translated into about 60% of gTLD domains under management being reachable via RDRS, which inevitably depresses requestor adoption and undermines “single-channel” expectations.

Authentication (especially for law enforcement) is a gating item

Community discussions repeatedly return to one practical question: who is the requestor, and can the registrar rely on that identity fast enough for urgent cases? ICANN’s own communications refer to ongoing work on an authentication protocol for law enforcement users during the extension period.

Integration and workflow efficiency are decisive

Registrars with mature disclosure processes are reluctant to “duplicate” work. The direction of travel is therefore technical: API-based integration that lets registrars map RDRS inputs into their internal tooling, reduce manual handling, and improve turnaround consistency, without forcing a single UI on everyone.

RDRS vs SSAD: why the distinction matters for strategy and compliance

SSAD (System for Standardised Access/Disclosure) is not a synonym for RDRS. SSAD is a policy construct developed through the EPDP Phase 2 process, with 18 interdependent recommendations covering accreditation, request criteria, response requirements, logging, auditing, and service levels.

ICANN’s Operational Design Assessment work illustrates why SSAD has remained complex and resource-intensive to implement, and why the community is now testing what can be improved incrementally via RDRS while policy deliberations continue.

Practical takeaway: RDRS is the operational “bridge” through 2027; SSAD (or a successor) is the potential “highway.” Planning must therefore assume evolution, not stability.

European data protection: how GDPR logic shapes disclosure decisions

For European stakeholders, the disclosure decision is rarely “policy-only.” It is a legal risk assessment structured around GDPR principles: lawful basis, necessity, proportionality, transparency, minimisation, retention, and accountability.

Lawful basis and the “legitimate interest” test

In most rights-holder scenarios, disclosure requests are framed around legitimate interest (Article 6(1)(f) GDPR logic), which requires (i) a legitimate interest, (ii) necessity, and (iii) balancing against the data subject’s rights and reasonable expectations. The CNIL and French legal materials frequently reflect this three-step logic.

Cross-border reality: one DNS, many legal regimes

A single domain name can involve a registrar in one jurisdiction, a registrant in another, and harm occurring across markets. RDRS helps standardise inputs, but it does not harmonise legal thresholds. As a result, outcomes will continue to vary unless and until enforceable service standards and authentication mechanisms mature.

A useful comparison point for France: AFNIC’s disclosure logic

While RDRS targets gTLDs, French operators and rights-holders are already familiar with structured disclosure models at the ccTLD level. AFNIC, for example, provides a formal route to request disclosure (lift of anonymisation) for .fr-type namespaces, illustrating that “structured request + evidence + legitimate interest” is operationally feasible, yet still fact-dependent.

Operational implications by stakeholder type

Registrars and registries: prepare for “standardisation pressure”

• If you are not participating, you risk being operationally and reputationally out of step with ICANN’s “comprehensive usage” direction, even before any mandatory shift occurs.

• If you are participating, the competitive differentiator becomes process maturity: intake quality, documented decision criteria, escalation paths for urgent cases, and technical integration capacity.

For further reading, we invite you to consult our analysis of ICANN registration data policy measures and their impacts.

Rights-holders and investigators: treat RDRS as one channel in a layered toolkit

RDRS remains a valuable path, but not a complete one. We recommend positioning it as:

• a first-line standardised intake for gTLD non-public data; and

• a case-building instrument that strengthens follow-on actions (takedown, registrar escalation, UDRP/URS, court measures) when disclosure is denied or delayed.

For further reading, we invite you to consult our complete guide to UDRP, Syreli, and international alternatives.

Privacy/proxy services: expect policy alignment to narrow discretion

One of the most sensitive gaps concerns access to underlying data behind privacy/proxy services, and how such requests should be handled in a standardised architecture. The policy alignment track explicitly connects RDRS evolution with privacy/proxy workstreams.

Corporate stakeholders: anticipate governance questions, not only “legal” questions

Large organisations operating globally should expect internal questions such as:

• Who is authorised to submit RDRS requests?

• What evidence threshold is required (fraud indicators, brand rights, consumer harm, phishing signals)?

• How do we log, retain, and audit outgoing requests and incoming data to meet internal compliance expectations?

Conclusion

The Registration Data Request Service (RDRS) is no longer a short experiment: with operations maintained through December 2027, it becomes the reference bridge for non-public gTLD registration-data requests, while the community debates whether to harden it into mandatory, authenticated, SLA-driven infrastructure. For European organisations, success will depend on combining high-quality evidence, disciplined disclosure theories, and well-sequenced enforcement paths that remain robust even when disclosure is refused.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Dreyfus & Associés works in partnership with a global network of attorneys specializing in Intellectual Property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

Q&A

1) Does RDRS replace WHOIS/RDDS?

No. WHOIS/RDDS remains the system for accessing registration data (often partially redacted), while RDRS is a separate channel for submitting disclosure requests.

2) Does RDRS provide automatic access to non-public WHOIS data?

No. There is no automatic disclosure: each request is assessed by the registrar on a case-by-case basis, based on the applicable legal framework and the supporting evidence provided.

3) What is SSAD and how is it different from RDRS?

SSAD is the policy framework proposed by the EPDP Phase 2 process, including recommendations on accreditation, request criteria, response requirements, auditing, and SLAs. RDRS is a pilot operational service collecting data and experience while those policy questions remain unresolved.

4) Why is “law enforcement authentication” such a central issue?

Because urgent, cross-border cases require reliable requestor identity verification. ICANN has identified authentication work as a priority improvement track during the extension period.

5) How should EU rights-holders frame RDRS requests under GDPR constraints?

Requests should be tightly scoped, evidence-driven, and aligned with lawful-basis logic (often legitimate interest), necessity, proportionality, and documented balancing, consistent with CNILstyle reasoning around Article 6(1)(f).

6) If RDRS fails, what are the fastest alternatives to stop abuse?

Depending on the facts: registrar/hosting takedown routes, platform abuse channels, and, when transfer or suspension is needed, UDRP/URS or ccTLD-specific procedures.

This publication is intended for general public guidance and to highlight issues. It is not intended to apply to specific circumstances or to constitute legal advice.