Sommaire

Introduction

Determining the ownership of a design and model is one of the most sensitive issues in industrial creation law. In practice, disputes rarely focus on the validity of the design or model itself but rather on the identity of the person authorized to exploit, oppose, or transfer the rights. Employment, subcontracting, collective creation, lack of a contract, or poorly anticipated registration are all sources of risk. In this article, we analyze how the ownership of a design and model is obtained and proven, under both French and European law.

Principle and criteria of ownership in design and model

Criteria for ownership of designs and models

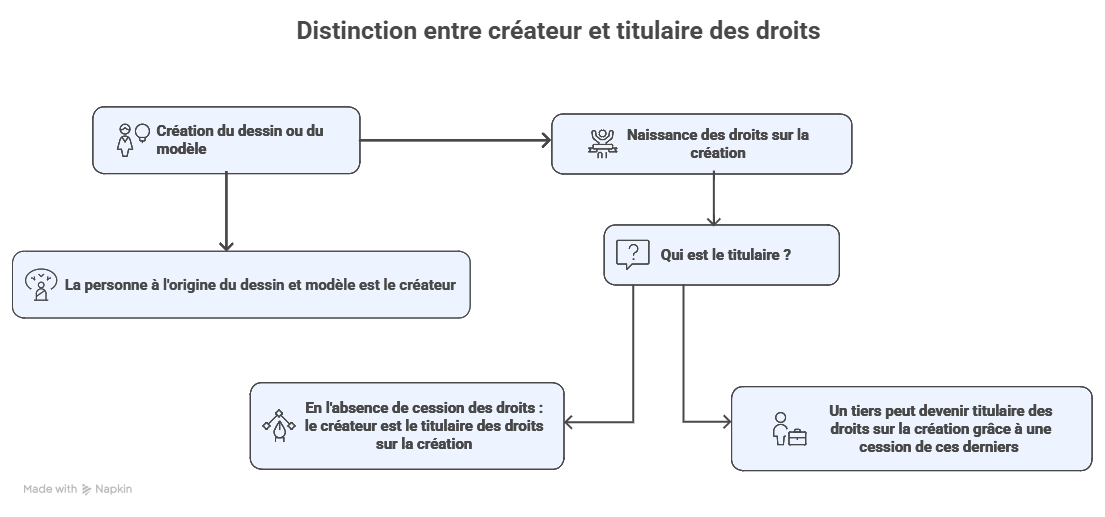

A design and model protect the appearance of a product or a part of a product, independently of its technical function. Ownership must be distinguished from material creation. The creator must be a natural person, while the holder may be a legal entity.

Under both French and European law, the logic is pragmatic: ownership is attributed to the person legally entitled to exploit the design, taking into account the context of its creation. The law sets out a principle, with presumptions and corrective mechanisms.

Principle of ownership: the central role of the creator

As a general rule, the design and model belong to its creator. This rule applies whether or not the design is registered. Creation confers an original right, provided that the design is new and has an individualized form.

In the event of a dispute, the courts examine the concrete elements proving the creative contribution: sketches, prototypes, digital files, email exchanges, annotated specifications. A mere idea or aesthetic directive is insufficient. Ownership is based on a personal creative contribution identifiable in the final form of the product.

Ownership disputes

1. Designs and models created by employees

The creation of a design by an employee in the performance of his duties is not regulated by law. In fact, the case law uses a slightly different reasoning than that used in copyright. Indeed, if copyright is inextricably personalist, the right of designs and models responds to a more economic logic. Thus, when the design is created by an employee in the performance of his duties or according to his employer’s instructions, the law provides a presumption of ownership in favour of the employer when the latter is at the origin of the application for registration. This rule aims to secure the economic exploitation of creations made in an organized and remunerated framework.

However, this presumption is not irrebuttable and assumes that the creation is indeed part of the tasks entrusted to the employee. If the design was designed outside the functions, without any link with the company’s activity, the ownership thus remains attached to the employee.

In fact, the absence of a precise contractual clause constitutes a major source of litigation. It is recommended that employment contracts should systematically include explicit clauses relating to the creation of designs and models, covering both ownership and operating terms.

2. Designs and models created by independent contractors or partners

The situation is radically different when dealing with an independent contractor, freelance designer, or industrial partner. Unlike employment, no legal presumption favors the client.

In the absence of a contract specifying the assignment or transfer of ownership, the contractor retains ownership of the rights, even if the creation was fully financed by the client. This situation is common in industries such as luxury, product design, or fashion, and constitutes a major legal risk.

The transfer of ownership must be explicit, written, and clearly defined, especially regarding territorial scope, duration, and modes of exploitation. A simple invoice or mention of “custom work” is legally insufficient.

Ownership presumptions and the value of registration

The registration of a design and model, whether national or European, creates a simple presumption of ownership in favor of the registrant. This presumption facilitates actions for infringement and defense of rights, but it can be overturned by contrary evidence.

Thus, a registrant may lose their ownership status if it is demonstrated that the registration was made without rights, particularly by a former employee, contractor, or partner acting in bad faith. European courts are particularly attentive to the circumstances of creation and prior contractual relationships.

The registration should, therefore, be viewed as a tool for securing rights, not as an absolute guarantee.

Securing ownership: best practices and legal strategies

To avoid future disputes, several levers should be combined:

• First, systematically contractually secure ownership at the outset of creative projects.

• Then, maintain dated evidence of creation and the design process.

• Finally, align the registration strategy with the legal reality of creation.

For example, an industrial company that registers a model created by an external studio without a written transfer may lose its rights during a nullity action. In contrast, a prior contractual audit would have secured the chain of rights at a lower cost.

Conclusion

Knowing how to determine the ownership of a design and model is essential for effectively protecting a strategic asset. Ownership is not presumed solely from funding or registration. It relies on a thorough analysis of the creation context, contractual relationships, and available evidence. Rigorous legal foresight remains the best safeguard against disputes.

Dreyfus & Associates assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

Q&A

1) What is the difference between creator and holder?

The creator is the material author of the design; the owner is the one who legally holds the exploitation rights. In some cases, the creator and the owner may be the same person, particularly when the creator retains all rights over his work.

2) Can ownership of a design or model be transferred without a written contract?

In principle, no. The transfer of ownership must be explicit, written, and recorded. The law requires that any transfer of rights (including ownership) be clearly documented to avoid disputes. In practice, this means that a simple invoice or verbal agreement is insufficient. A detailed contract defining the scope of the transferred rights (territory, duration, exclusivity, etc.) is always preferable.

3) What is the procedure to recover a design or model if a contractor refuses to transfer the rights?

In this case, it is recommended to act quickly by asserting ownership of the design or model based on contractual elements. If no transfer contract was signed, jurisprudence may, however, consider tacit agreement or contextual elements showing the intention to transfer ownership, which can be crucial.

4) What evidence can be used to challenge the ownership of a registered design in Europe?

In order to challenge the ownership of a registered design, relevant evidence may be :

• Communications

• Original sketches

• Testimony about prior discussions

• Proof of prior authorship

• A preliminary version of the design

• Exchanges between the creator and the company

• Proof of funding, may also be essential to contest a design registration.

Additionally, the question of bad faith during registration may be decisive.

5) Does a creation carried out during a notice period or a period of suspension of the employment contract belong to the employer?

Not necessarily. The period of notice or suspension (leave without pay, sick leave, layoff) does not automatically eliminate the contractual relationship, nor does it imply an automatic devolution of rights.

The analysis will focus on the concrete circumstances of creation, the use of the company’s resources, the link with previous missions and the possible existence of a transfer clause. In practice, these situations are particularly conducive to subsequent disputes.

The purpose of this publication is to provide general guidance to the public and to highlight certain issues. It is not intended to apply to particular situations or to constitute legal advice.