Sommaire

Introduction

In the field of artificial intelligence (AI), trained models represent a major technological advancement derived from extensive training datasets. Unlike the raw data forming the original datasets, an AI model captures the relationships and patterns learned during the training process. Once trained, it becomes an autonomous intangible asset, embodying technical knowledge extracted from the underlying data.

The legal protection of such models has therefore become an increasingly significant issue. While the question of protection of AI-generated works, authorship, and liability for infringement have already been extensively analyzed, the legal qualification and protection regime applicable to the trained model itself raise distinct and specific challenges requiring separate examination.

The sui generis database right: an ill-suited regime for AI models

The training of an AI system relies on a database serving as an informational reservoir. However, the resulting model is not equivalent to the original database. Unlike a mere aggregation of structured data, an AI model incorporates relationships, weightings, and patterns learned during the training process. It constitutes an abstract representation enabling prediction, classification, or analysis of new data.

This specificity raises a qualification issue. The sui generis database right, established by Directive 96/9/EC and transposed into Article L.341-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code, protects substantial investment in the acquisition, verification, or presentation of systematically organized data. By contrast, an AI model does not consist of individually accessible structured data, but rather a dynamic configuration resulting from algorithmic learning. It does not reproduce the original database, nor does it allow extraction of the initial data as such.

Accordingly, although it relies on a potentially protected training dataset, the AI model itself generally falls outside the scope of the sui generis database right. Its algorithmic and relational nature fundamentally differs from the static and organizational logic inherent in databases.

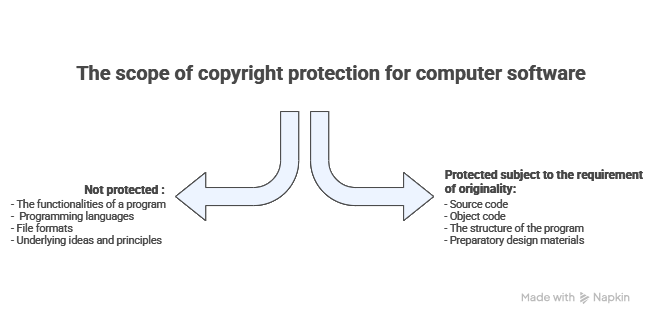

Copyright: partial protection focused on code expression

In theory, copyright protection may apply to certain elements of an AI model if they reflect free and creative choices constituting the author’s own intellectual creation, as established in the Pachot decision (French Court of Cassation, Plenary Assembly, March 7, 1986, No. 83-10.477).

In practice, such protection primarily concerns the source code or software architecture implementing the model, insofar as these fall within the legal regime applicable to software (Article L.112-2, 13° of the French Intellectual Property Code). To date, however, no judicial decision has recognized autonomous copyright protection for a trained AI model as such.

In case SAS Institute (CJEU, May 2, 2012, C-406/10), the Court held that while a software is protected by copyright, its functionalities and the ideas and principles underlying it are not. Transposed to AI models, this reasoning requires distinguishing between the code implementing the model, which may be protected, and its functionalities (text generation, classification, prediction) as well as its underlying statistical or architectural principles, which remain unprotectable ideas.

The most complex issue concerns the weights and parameters of a trained neural network: can they be regarded as “expression” for copyright purposes? The restrictive approach adopted in the SAS Institute case excludes ideas, principles, and underlying mathematical methods from protection. The qualification of weights and parameters, materializing the outcome of algorithmic learning, remains uncertain in the absence of specific case law.

Patent law: the requirement of a further technical effect

Patent law does not permit protection of an AI model as an abstract mathematical construct. Algorithms, mathematical methods, and computer programs are excluded from patentability “as such” pursuant to Article L.611-10 of the French Intellectual Property Code.

However, an invention implementing an AI model may be patentable if it provides a technical solution to a technical problem and produces a further technical effect, as clarified by the EPO Technical Board of Appeal (T 1173/97 – Computer program product, July 1, 1998).

In other words, it is not the model itself that may be protected, but its integration into a concrete technical application, such as improving computer performance, optimizing an industrial process, processing technical signals or images, or managing a physical device.

Patentability therefore requires that the model effectively contributes to the technical character of the invention beyond the mere execution of calculations or statistical learning. In practice, direct protection of an isolated AI model appears unlikely; only its incorporation into a system or process producing an identifiable technical effect may justify patent protection.

Trade secrets: a pragmatic protection for trained parameters

In practice, trade secret protection constitutes the most appropriate mechanism for safeguarding trained AI models. Under Articles L.151-1 et seq. of the French Commercial Code, information is protected where it is not generally known or readily accessible, has commercial value because of its secrecy, and is subject to reasonable protective measures.

The weights, parameters, and internal configurations of an AI model frequently satisfy these criteria: they are non-public, result from substantial investments in data and computation, and confer a decisive competitive advantage. Protection requires an effective security policy, including technical access controls, contractual confidentiality limitations, and appropriate organizational measures.

From this perspective, trade secret law appears to be the most coherent legal tool for preserving the economic value of proprietary AI models.

Conclusion

A trained AI model does not fully fit within any traditional intellectual property regime. It is neither a database within the meaning of the sui generis right, nor a work protected as such under copyright, nor an independently patentable invention absent a further technical effect.

Its protection therefore relies on a combined approach: copyright for the code, patent protection for certain technical applications, and, above all, trade secret protection to safeguard trained weights and parameters. Rather than a single exclusive right, it is a coherent and anticipatory legal strategy that ensures effective protection of this strategic intangible asset.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1. Are models derived from an open-source model legally independent?

It depends on the applicable license terms. Certain licenses impose obligations to share modifications or derivative works.

2. Are non-compete clauses relevant for protecting a model?

They may complement contractual protection strategies, particularly to prevent the reuse of equivalent know-how by employees or partners.

3. Can training a model on protected data legally contaminate the model?

In principle, no, since the model does not reproduce the data. However, if protected data remain identifiable or retrievable, infringement risks may arise.

4. Does the protection of AI models require legislative reform?

The doctrinal debate is ongoing. Some advocate for a sui generis protection regime for AI systems, but no specific reform has yet been planned.

5. Can an AI model constitute a strategic asset for valuation or investment purposes?

Yes. It may be subject to specific due diligence in M&A transactions or fundraising operations.

The purpose of this publication is to provide general guidance to the public and to highlight certain issues. It is not intended to apply to particular situations or to constitute legal advice.