How does the French Digital Republic Act regulate the operation of online platforms?

Introduction

The French Digital Republic Act of October 7, 2016 laid the foundation for a structured regulatory framework governing online platforms in France. It introduced transparency, fairness and accountability obligations designed to rebalance the relationship between platforms, professionals and users.

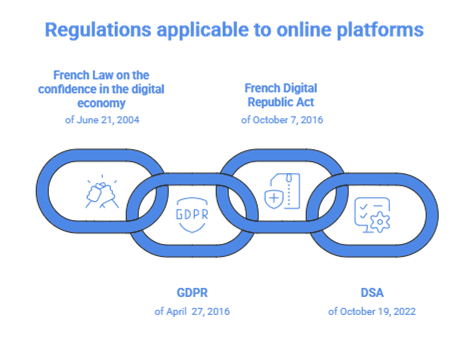

In an ecosystem now largely shaped by the GDPR and the Digital Services Act (DSA), these obligations must be reassessed and updated. In this article, we offer a comprehensive analysis of the actual scope of the statutory provisions: first, what the law truly provides for, and then how those provisions fit into a legal landscape that has been profoundly reshaped since 2016.

Core obligations imposed on online platforms

Legal definition of online platforms

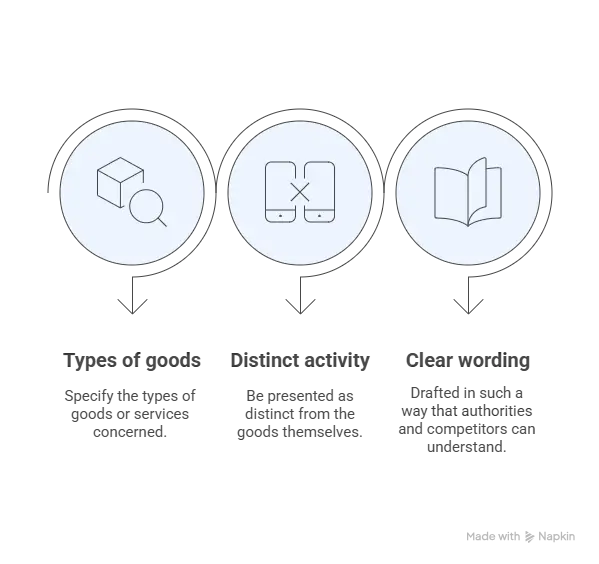

The Digital Republic Act introduced a precise definition of online platforms, formerly codified in the old Article L.111-7 I of the French Consumer Code. Services were considered platforms when they professionally offered, whether for remuneration or not, an online communication service to the public based on:

- The ranking or referencing of content, goods or services;

- The facilitation of interactions between several parties for the purpose of a transaction.

This definition covered a broad range of services: comparison tools, marketplaces, directories, search engines, social networks and intermediation services.

Its purpose was clear: to acknowledge the significant influence of these operators and to establish a protective framework built on three core principles, transparency, fairness and responsibility.

Article L.111-7 I of the Consumer Code was revoked in 2022. The applicable definition is now the one set out in the Digital Services Act, which qualifies an online platform as any intermediary service that stores and makes information accessible to the public at the request of users.

Differentiation between operators

The law distinguishes between:

- Online platform operators, subject to general transparency rules;

- Influencer platforms or hyperscale operators, now primarily regulated at the EU level by the DSA.

This structure enables obligations to be calibrated according to the platform’s economic influence.

Strengthened transparency and fairness requirements

Enhanced information obligations

Article L.111-7 of the French Consumer Code requires platforms to inform users of the criteria determining the ranking of content or offers. This information must be clear, intelligible and easily accessible.

This obligation, innovative in 2016, anticipated today’s concerns regarding algorithmic manipulation and the transparency of recommendation systems.

Disclosure of contractual relationships

Platforms must also indicate whether the advertiser or seller is acting as a professional, a consumer, or an uncertified reseller.

This enables users to determine whether consumer protection provided by law applies.

Identification of sponsored content

The law requires clearly identifiable disclosures when content has been paid for or promoted.

These provisions foreshadowed today’s standards set by:

- The ARPP (French Autorité de régulation professionnelle de la publicité) for influencers,

- The DSA for digital services,

- Established case law on hidden advertising.

Increased accountability of digital actors

Reporting mechanisms

Platforms must provide a user-friendly mechanism enabling individuals to report illegal content, including: counterfeiting, hate speech, privacy violations, fraud, and other unlawful activities.

This obligation strengthens the notice-and-takedown regime established by the French Law on confidence in the digital economy (LCEN) of June 21, 2004 by requiring faster action.

Communication of pre-contractual information

When a platform connects professionals, sellers or service providers with consumers, it must provide a space enabling them to communicate the pre-contractual information required under Articles L.221-5 and L.221-6 of the French Consumer Code.

Fair information on online reviews

Since the French Decree of September 29, 2017, adopted to clarify the Digital Republic Act, platforms displaying reviews must disclose:

- Their moderation methods,

- Any financial consideration,

- Their verification methodology.

These obligations aim to reduce fake reviews, a major concern for both the DGCCRF and French courts.

Interactions with European regulations

Compatibility with the GDPR

The Digital Republic Act paved the way for enhanced personal data protection, now fully governed by the GDPR.

Platforms must ensure:

- Lawful and transparent processing,

- Data minimisation,

- Protection of sensitive data,

- Security measures proportionate to the risks.

The Act has been largely absorbed by this EU framework while retaining its additional economic transparency requirements.

Complementarity with the Digital Services Act

The DSA, applicable since 2024, has established a comprehensive EU-wide regime for platforms. The DSA notably imposes increased responsibility on platforms regarding the moderation of illegal or harmful content. They must implement mechanisms to detect and remove such content, failing which they may face sanctions.

French Digital Republic Act remains relevant, particularly for:

- Economic fairness obligations,

- Online review regulation,

- Consumer information duties.

Oversight and sanctions

The competent authorities include: the DGCCRF, CNIL, Arcom, and civil and criminal courts.

Sanctions can include fines, corrective measures, and even temporary bans on operations.

Practical considerations for professionals

Businesses operating a platform must now navigate several layers of regulation: the Digital Republic Act, LCEN, GDPR, DSA and the French Consumer Code.

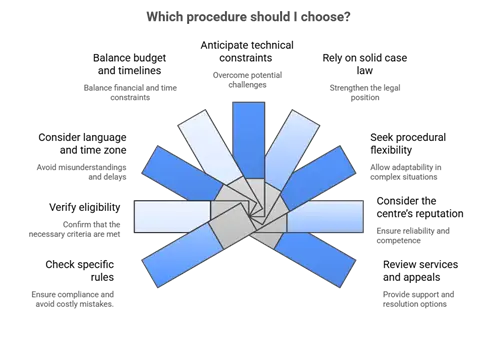

To ensure robust compliance, platforms must:

- Map national and EU obligations,

- Document ranking criteria,

- Enhance algorithmic transparency,

- Structure moderation procedures,

- Anticipate regulatory requests,

- Update their terms of use, privacy policies and notices.

Conclusion

The Digital Republic Act remains a fundamental component of the French regulatory framework for online platforms. It establishes an environment based on transparency, responsibility and user protection, now reinforced by the GDPR and the Digital Services Act. Businesses must adopt an integrated approach combining legal compliance, algorithmic governance and consumer protection to secure their digital operations.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1.Can a platform be held liable for content posted by a user?

Yes. A platform becomes liable if it fails to remove manifestly illegal content promptly after being informed of it.

2.Can a user challenge a platform’s decision to remove content?

Yes. Platforms must provide an internal complaint mechanism allowing users to contest removal or delisting decisions. Under the DSA, this mechanism must be accessible and include human review.

3.Can French law require a platform to disclose the identity of a user who posted illegal content?

Yes, but only under strict conditions. Disclosure can only be ordered by a judicial authority when there is evidence of illegal activity.

4.Must a platform located outside the EU comply with French law when targeting French users?

Yes. If it targets the French or EU market, it remains subject to local legislation.

5. What best practices should online platform operators adopt?

Platform operators should implement a comprehensive compliance strategy that integrates both national and European legal requirements. This includes documenting ranking criteria, strengthening transparency in commercial practices, structuring content moderation procedures, ensuring the reliability of online reviews, and regularly updating terms of use, privacy policies and mandatory disclosures.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance to the public and highlight certain issues. It is not intended to apply to specific situations or constitute legal advice.