Sommaire

Introduction

When a trademark is registered to designate essential oils, its owner may, in practice, not market these substances in their pure form. They may be creams, sprays, or even impregnated textiles, all enriched with essential oils but without these being sold as such. In such a context, a competitor may well bring an action for revocation of the trademark, considering that the declared use does not correspond to the registered category.

In a ruling dated May 14, 2025, the French Court of Cassation confirmed that such use is not sufficient to maintain trademark protection for the category “essential oils.” This decision has significant practical implications for trademark owners active in the aromatherapy, cosmetics, and wellness sectors.

The Skin’Up case

The company Skin’Up was the owner of the word trademark “SKIN’UP,” designating “essential oils” (class 3). In reality, it did not commercialize essential oils in vials. Its business mainly focused on slimming mists, cosmeto-textiles, and other products enriched with essential oils.

The company Univers Pharmacie, the owner of several “UP SKIN” trademarks, brought an action for partial revocation against the “SKIN’UP” trademark, considering confusingly similar to its own signs, on the grounds of insufficient use of that trademark for products in class 3.

The INPI recognized the action for revocation as partially justified and upheld the “SKIN’UP” trademark for “essential oils” and “cosmetics.” Univers Pharmacie appealed to the French Court of Cassation and asked the following question: is the marketing of textiles containing essential oils sufficient to consider that there has been genuine use of the trademark for cosmetics and essential oils?

In its ruling of May 14, 2025, the French Court of Cassation set aside the judgment of the Court of Appeal and reaffirmed a strict interpretation of genuine use in trademark law.

- Regarding “cosmetics”: The Court reiterated that the essential criterion for distinguishing between products is their purpose and intended use (the criterion of the autonomous subcategory). It therefore ruled that the Court of Appeal should have verified whether cosmeto-textiles constituted an autonomous subcategory within cosmetics. The use of the trademark on a distinct subcategory (such as cosmeto-textiles) is not sufficient to prove use for other products in the category (such as conventional cosmetic creams).

- Regarding “essential oils”: The Court ruled that the presence of essential oils in the composition of a product (in this case, cosmetotextiles or a mist) cannot, in itself, be considered proof of use of the trademark for “essential oils” as a separate product. The Court clearly distinguished between the ingredient and the designated finished product. Marketing a product containing essential oils is not the same as marketing essential oils, just as selling a car is not the same as selling steel.

By setting aside the decision of the Court of Appeal, the Court of Cassation logically reaffirmed the principle of specialty, which stipulates that protection only applies to the goods or services for which the trademark is actually used.

The concept of use

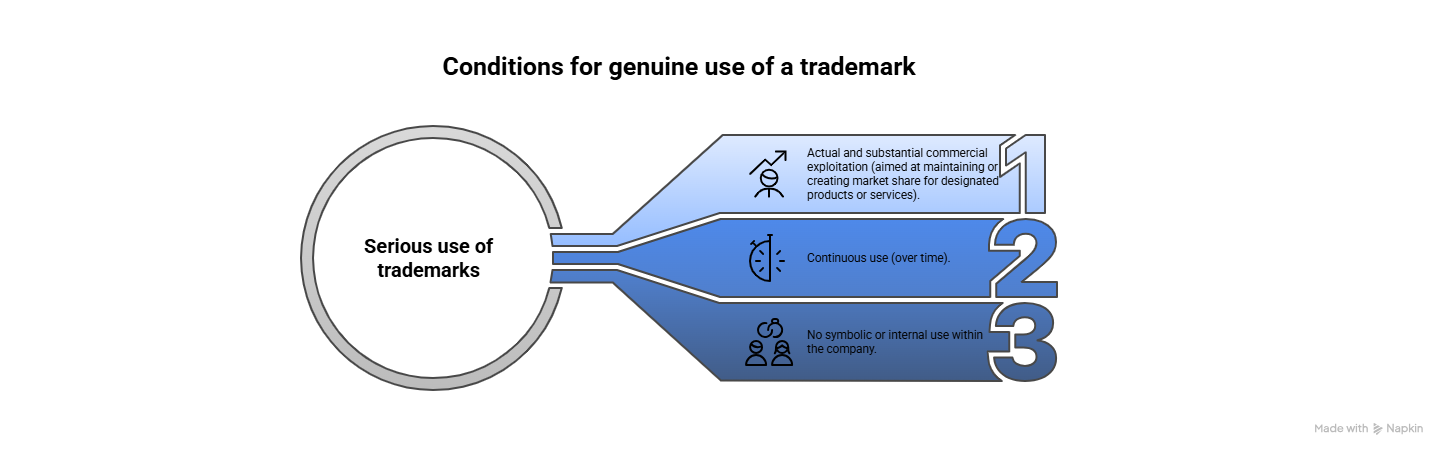

Genuine use of the trademark is not a mere formality, but a fundamental legal obligation. The owner must demonstrate effective, genuine, and uninterrupted use of the trademark for a period of five years after its registration, otherwise, protection will lapse for the goods or services for which no use has been proven.

This requirement is based on the principle that the owner’s interests should not infringe on the freedom of competitors to do business. This is why European case law, which is similar to that of the French Court of Cassation, takes a strict approach, particularly in cases where the wording of the registration is broad.

The key principles inspired by European case law are as follows:

- The use of a product belonging to a broad category is not sufficient to cover the entire category

- When the category is sufficiently broad, it is possible to distinguish autonomous subcategories of products based on their purpose and intended use

- If such subcategories exist, use of the trademark must be proven for each of them.

The ruling confirms that general or “indirect” use is not sufficient. Use must be genuine, distinct, and identifiable for each subcategory.

In practical terms:

If you designated “essential oils” in your trademark, but you do not sell them, the protection of your trademark may be at risk.

Here are five common pitfalls in trademark exploitation:

- Registering too many products or classes without a clear exploitation strategy

- Thinking that the use of an ingredient is sufficient to cover the corresponding category

- Neglecting segmentation by product type (which judges are increasingly requiring)

- Lacking evidence of actual use in the event of a dispute

- Ignoring or downplaying revocation actions (these are never mere formalities)

To learn more about the concept of use in trademark law, we invite you to read our previously published article on the subject.

What you can do right now

Do I actually market every product listed in my trademark registration?

If the answer is no, here are the steps to follow:

- Check your classes and designations

- Class 3: essential oils, cosmetics, soaps, etc.

- Class 5: pharmaceutical products, supplements, etc.

- Class 35: product sales, marketing, etc.

For each product, ask yourself: is it actually being marketed under your trademark?

- Gather evidence of use

- Invoices, purchase orders

- Packaging and labels mentioning the trademark

- Product images

- Social media posts, e-commerce sites

In the absence of proof of use: real risk of revocation.

Conclusion

Trademark protection for a category of products requires actual and direct use in that category.

Therefore, marketing a product containing essential oils is not sufficient to justify genuine use of the trademark for “essential oils” products.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1. What risks does a trademark owner face if the use of their trademark is deemed insufficient for certain categories of products during revocation proceedings?

They risk losing some (or all) of their rights to the trademark for the products or services that are not being used. This means that third parties will be free to register or use similar trademarks for these products, reducing the scope of the original protection.

2. What is meant by an “autonomous subcategory” of products, and why is this concept important for maintaining a trademark?

An autonomous subcategory is a distinct group of products within a broader category, identified by their purpose and intended use (for example, class 3 covers cleaning products and non-medicinal toilet preparations and cosmetics, with subcategories including cosmetics, perfumery, and makeup). If a category can be divided into autonomous subcategories, use of the trademark for one subcategory does not prove use for the others. The owner therefore risks forfeiture for the subcategories that are not exploited.

3. How does the French Court of Cassation distinguish between the use of a trademark for a category of products and its use for specific subcategories?

It applies the criteria of the purpose and intended use of the products. If these criteria reveal distinct uses and markets, then the products form autonomous subcategories and the use of a trademark in one does not constitute use in the others.

4. How can I prove that I am using my trademark for a category of products?

To prove genuine use of your trademark, you must gather concrete evidence of use for the designated products. This includes invoices and purchase orders, packaging and labels bearing the trademark, product images, and posts on social media or e-commerce sites. Without such evidence, you run a real risk of forfeiture.

5. Is it risky to designate too many classes or products when registering a trademark?

Yes. An overly broad registration without a strategy can weaken the trademark. It is better to target specifically the products that are already being used or that you plan to use.