Sommaire

Introduction

In trademark law, the protection granted to a well-known earlier trademark requires, in the context of an opposition or an appeal, a dual assessment:

- First, the likelihood of confusion under Article L. 713-2 of the French Intellectual Property Code (CPI);

- Second, damage to reputation, as provided for in Article L. 713-3 CPI.

The decision delivered by the Versailles Court of Appeal on October 22, 2025 in opposition proceedings initiated by Chanel against the trademark application “COCO SHAOUA” provides a landmark illustration of how these two concepts are assessed when a famous earlier trademark invokes both confusion and dilution.

We provide below a detailed analysis of the procedure, the Court’s reasoning, and the key takeaways for intellectual property professionals.

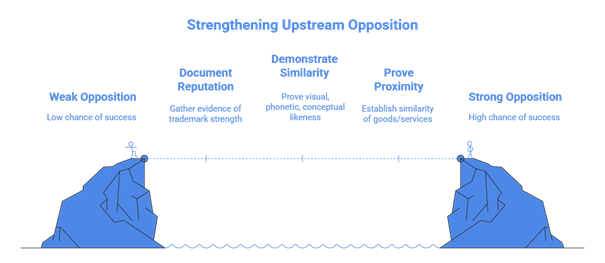

Opposition strategy: key elements to strengthen upstream

To maximise the chances of success in an opposition based on confusion or reputation, it is essential to:

- Document the reputation of the earlier trademark: association studies, surveys, turnover figures, market share data

- Demonstrate similarity between the signs (visual, phonetic, conceptual)

- Prove proximity or similarity of the goods and services

- Establish the existence of a mental link with the earlier trademark when invoking damage to reputation

Where one of these elements is missing or weakened, the opponent’s position is significantly undermined, as illustrated in the Versailles Court of Appeal decision of October 22, 2025.

Facts and procedural background of the October 22, 2025 decision

The earlier trademark: “COCO”

Chanel owns the verbal trademark “COCO,” covering soaps, perfumery and cosmetics in Class 3. The trademark enjoys significant public recognition as a direct reference to the Chanel universe and forms the basis of the opposition.

The contested trademark: “COCO SHAOUA” (classes 3 and 4)

A trademark application for the verbal sign “COCO SHAOUA” was filed for goods in Class 3 (cosmetics) and Class 4 (candles). Chanel contested the application on two grounds:

- A likelihood of confusion regarding Class 3 goods

- Damage to the reputation of the earlier trademark “COCO,” particularly in relation to Class 3 goods.

Opposition Before the INPI and the Director General’s Decision

Chanel filed an opposition before the French IP Office (INPI) against “COCO SHAOUA.”

The INPI Director General, while acknowledging the reputation of the earlier “COCO” trademark, rejected the opposition. He found that the signs were insufficiently similar to give rise to a likelihood of confusion and thus allowed the registration of “COCO SHAOUA.”

Chanel’s appeal before the Court of Appeal

Following the rejection, Chanel lodged a cancellation action before the Versailles Court of Appeal. The company argued that “COCO” was highly distinctive visually, phonetically and conceptually, and that “COCO SHAOUA” created both a likelihood of confusion and damage to reputation.

The Court delivered its decision on October 22, 2025.

The Court of Appeal’s assessment of likelihood of confusion

Similarity of the signs

Chanel argued that “COCO SHAOUA” incorporated the sequence “COCO” in its attack position, leading consumers to associate it instantly with the earlier trademark. The company also contended that the syllable “SHA” could phonetically evoke “CHANEL,” reinforcing a conceptual association.

The Court held otherwise. It noted that the word “coco,” when used as a common noun (e.g., as an ingredient or scent), does not function exclusively as a distinctive sign for Chanel in the mind of consumers. It further considered that the fantasy term “shaoua” was equally prominent within the sign “COCO SHAOUA,” such that the trademark would be perceived globally.

The Court therefore concluded that the visual differences (one word vs. two words), phonetic differences (two syllables vs. four), and conceptual differences between the signs were sufficient to exclude similarity.

Proximity of the goods

The Court acknowledged that the goods in Classes 3 and 4 were similar or closely related to those covered by the earlier trademark, which could, in principle, reinforce the likelihood of confusion. However, the lack of similarity between the signs prevailed: product proximity alone was insufficient to create confusion.

Conclusion: no likelihood of confusion

The Court rejected Chanel’s claim on likelihood of confusion, holding that the company had not demonstrated that “COCO SHAOUA” would be perceived as originating from, or linked to, Chanel by the relevant public.

The Court of Appeal’s assessment of damage to reputation

Recognition of the reputation of “COCO”

The Court confirmed that “COCO” benefits from recognised reputation, as acknowledged by the INPI. This reputation gives rise to autonomous protection under Article L. 713-3 CPI, allowing action even without confusion, where the contested sign creates dilution or parasitism.

Low intrinsic distinctiveness of the term “COCO”

However, the Court emphasised that the term “coco” is a common, polysemous noun (e.g., coconut, ingredient, scent), resulting in limited intrinsic distinctiveness. Reputation alone cannot compensate entirely for this weakness.

Assessment of “COCO SHAOUA” and lack of mental link

The Court found that the combination of “coco” with the fantasy term “shaoua” did not create a mental link with the earlier trademark “COCO.”

As the existence of such a link is a prerequisite under Article L. 713-3 CPI, the claim for damage to reputation could not succeed.

Conclusion: no damage to reputation

The Court therefore dismissed Chanel’s claim, finding no confusion and no dilution of the earlier reputed trademark.

To learn more about the scope of protection for a trademark’s reputation, please see our previously published article.

Conclusion

The Versailles Court of Appeal decision of October 22, 2025 demonstrates that the protection of a well-known earlier trademark does not dispense with a thorough assessment of sign similarity and the overall perception of the contested trademark. Despite Chanel’s reputation, the Court held that “COCO SHAOUA” was sufficiently distinct from “COCO” to exclude both confusion and dilution.

For trademark owners, this decision underscores the need for vigilance and meticulous preparation when engaging in opposition proceedings.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1. Can an opposition be based solely on damage to reputation without likelihood of confusion?

Yes. Article L. 713-3 CPI allows action against a sign that damages the reputation of an earlier trademark even where no likelihood of confusion exists, provided that the earlier trademark’s reputation is proven and that a mental link is established.

2. Does a trademark consisting of a first name or nickname automatically benefit from enhanced protection?

No. Even a famous first name does not necessarily acquire strong distinctiveness. Courts evaluate its intrinsic character: a common first name, even if associated with a public figure, may remain weakly distinctive. Reputation does not convert a common word into a strongly distinctive trademark.

3. Does the presence of a generic term within a composite sign always prevent a likelihood of confusion?

No. A generic term may remain dominant if the rest of the sign is descriptive or secondary. It depends on the overall impression. In this case, the fantasy element “shaoua” neutralised the impact of “coco,” but other cases have found confusion despite a generic term where the dominant attack remained preponderant.

4. What types of evidence best support the existence of a mental link in reputation-based actions?

The most persuasive evidence includes recent market studies, association surveys, media exposure analytics and demonstrations of likely marketing free-riding. Judges accord significant weight to robust, recent and verifiable data.

5. Can a weakly distinctive trademark still be protected effectively?

Yes, provided the owner demonstrates either extensive use leading to acquired distinctiveness, or an arbitrary character in the relevant market.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance to the public and to highlight certain issues. It is not designed to apply to specific situations, nor does it constitute legal advice.