Sommaire

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Who is the author and initial rights holder of a work?

- 3 Works created by employees, contractors, or public officials: who owns the rights?

- 4 Works with multiple authors: collaboration, derivative works and collective works

- 5 Assignment and licensing: how can copyright be transferred or exploited?

- 6 Duration of protection and contractual safeguards

- 7 Conclusion

- 8 FAQ

Introduction

In an environment where creative content circulates faster than ever, determining the owner of a copyright-protected work remains a key legal issue for businesses, creators, and all innovation stakeholders. French law follows a particularly protective regime, grounded on the primacy of the author, strict requirements for copyright assignments, and narrowly framed exceptions, especially for employees, external service providers, collaborative works, and software.

Please find bellow the essential rules governing copyright ownership and transfer in France, together with best contractual practices to ensure secure exploitation of a work.

Fundamental principle: the author is always the natural person who created the work

The French Intellectual Property Code (“IPC”) is unequivocal: the author is the creator of the work, regardless of status or function. The author holds:

- Moral rights, perpetual, inalienable, and imprescriptible (Art. L121-1 IPC);

- Economic rights, transferable and exploitable under contract (Art. L122-1 et seq. IPC).

Presumption of authorship: the person whose name appears on the work

When a work is disclosed under a particular name, that person is presumed to be the author, unless proven otherwise. This presumption is central in disputes relating to the origin of a creation.

Orphan works: a specific regime

If no author can be identified, the work is considered an orphan work, and it remains protected. Its use is strictly limited to cultural, educational or research purposes, excluding commercial exploitation.

Works created by employees, contractors, or public officials: who owns the rights?

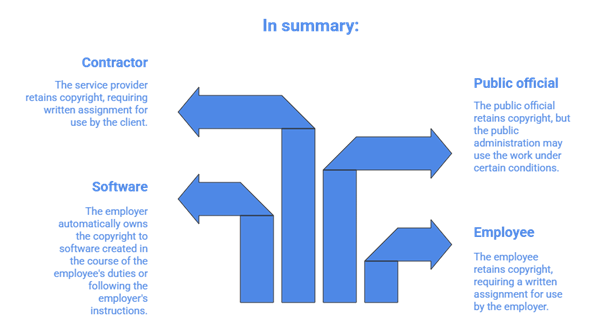

Employees: no “work for hire” doctrine under French law

Contrary to common-law systems, French law does not recognise automatic transfers of copyright to employers.

Even when created within the scope of employment, the employee remains:

- The author, and

- The initial owner of economic rights.

To exploit the work, the employer must obtain a written copyright assignment, compliant with Articles L131-1 et seq. IPC.

The software exception

Software is subject to a major exception under article L113-9 IPC: the employer automatically acquires economic rights when the software is created:

- In the course of the employee’s duties, or

- According to the employer’s instructions.

This rule strongly protects technology companies.

Public officials: a regime governed by the intellectual property code

Public officials are subject to a specific copyright regime, set out in Articles L131-3-1 and L111-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code. As a general rule, the public official remains the author and the initial rights holder, but the administration may exploit works created in the performance of the official’s duties or in accordance with instructions received, to the extent necessary for the fulfilment of the public service mission. Any exploitation exceeding this purpose requires the express authorisation of the author, together with appropriate remuneration.

Teachers-researchers, however, constitute a notable exception: owing to their academic freedom, they retain full control over the exploitation of their works, even when created in the course of their duties. This framework seeks to balance the protection owed to the author with the operational needs of the public service.

Independent Contractors: Assignment Required

The rule is clear: a contractor remains the author and owner of the work unless a written assignment is executed in favour of the commissioning party.

Without such an assignment, the work cannot legally be exploited, even if fully paid for.

Collaborative works: joint ownership

A work created by several individuals is a collaborative work under Articles L113-2 (para. 1) and L113-3 IPC.

Co-authors jointly own the rights, and any exploitation requires their mutual consent.

Derivative works: authorisation required

When a work derives from a pre-existing work (adaptation, transformation, remix of a protected work), the author of the derivative work must obtain the right holder’s authorization, pursuant to article L113-4 IPC, which governs composite works.

Collective works: a specific ownership regime

Article L113-2 (para. 3) IPC defines a collective work as a creation developed at the initiative of a natural or legal person who publishes and discloses it under their name and assumes editorial responsibility, with the individual contributions merged into an inseparable whole.

This regime frequently applies to:

- Press publications,

- Content created by creative agencies,

- Websites and digital platforms,

- Editorial and institutional materials.

A work qualifies as collective when three cumulative criteria are met:

- A decisive initiative and overall control by the commissioning entity, exercising genuine editorial oversight;

- Integration of individual contributions into a unified whole, with no separable rights;

- Disclosure under the commissioning entity’s name, appearing as the sole project owner.

Where these conditions are fulfilled, the legal entity is the original owner of the economic rights, eliminating the need to obtain individual assignments from contributors.

Assignment and licensing: how can copyright be transferred or exploited?

Copyright assignment: strict formal requirements

A valid assignment must:

- Be in writing;

- Specify each transferred right (reproduction, representation, adaptation, etc.);

- Detail the territory, duration, and media;

- Include proportional or fixed remuneration compliant with the ipc.

General formulas such as “all rights assigned” are invalid.

Licences: a flexible alternative

A licence authorises use without transferring ownership. It must be:

- Limited in duration (perpetual licences are void),

- Clear, with ambiguities interpreted in favour of the author.

Certain licences are statutory (library lending, private copying, educational uses) and involve mandatory remuneration.

No registration requirement

France requires no administrative formalities to recognise assignments or licences.

However, maintaining records is strongly recommended for evidentiary purposes.

Duration of protection and contractual safeguards

Standard duration: 70 years post mortem

Economic rights expire 70 years after the author’s death.

For collective, anonymous, or pseudonymous works, protection lasts 70 years from 1 January following the year of publication (Art. L123-3 IPC).

Best contractual practices

We systematically recommend:

- Signing contracts before delivery of the work;

- Drafting by distinct rights (reproduction, adaptation, etc.);

- Precise identification of the work and all versions;

- Verifying the chain of title (employees, contractors, subcontractors);

- Including warranties against eviction and infringement.

A frequent example: a company commissioning a website without an assignment is legally unable to modify its design or entrust maintenance to a third party.

Conclusion

Determining the ownership of a copyright-protected work in France requires balancing author protection, contractual precision, and narrowly framed legal exceptions. Legal certainty depends on a deep understanding of IPC mechanisms and carefully drafted contracts.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1. Can an author assign copyright before the work is even created?

Yes, but only under strict conditions. French case law prohibits broad assignments of future works unless the scope or type of works is sufficiently defined. Production agreements (video games, audiovisual works, commissioned creations) often rely on this framework.

2. How can authorship or prior creation be proved in case of a dispute?

Evidence may include Soleau envelopes (INPI), blockchain timestamps, bailiff reports, digital archives, dated project files, or emails. No formalities are required, but reliable proof of date is essential.

3. Can an employer prevent an employee from reusing a work created during employment?

Yes, if the employee has assigned the economic rights under the IPC. Without a written assignment, the employer has no exploitation rights.

4. Who owns the rights in a work published under a pseudonym?

The person identified as author upon disclosure benefits from a presumption of authorship.

5. Can a licence be granted without a duration limit?

No. Perpetual licences are void under French law.

6. Can AI be considered an author?

No. Only a human being can be recognised as an author under the IPC.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance to the public and highlight certain issues. It is not intended to apply to specific situations or constitute legal advice