Sommaire

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Understanding the withdrawal and renunciation of a trademark: key concepts and fundamental distinctions

- 3 Trademark withdrawal and opposition: a fast and regulated conflict-resolution tool

- 4 Renunciation of a trademark in the context of invalidity and revocation actions: radically different legal effects

- 5 Conclusion

- 6 Q&A

Introduction

At first glance, the withdrawal or renunciation of a trademark may appear to be a simple and pragmatic way to defuse a trademark dispute. Behind this apparent simplicity, however, lie far-reaching legal consequences, sometimes irreversible, which may durably affect the value of a strategic asset, the coherence of a trademark portfolio and the rights holder’s position in contentious proceedings.

In the context of administrative disputes, whether before the INPI or the EUIPO, these mechanisms must be handled with caution. Poorly anticipated, they may turn an amicable solution into a structural weakening of rights. When properly mastered, on the other hand, they become an effective, swift and economically rational negotiation tool.

Understanding the withdrawal and renunciation of a trademark: key concepts and fundamental distinctions

Renunciation consists of a partial or total abandonment of rights by the trademark owner. When total, the trademark simply disappears from the register. When partial, it results in a reduction of the scope of protection, by limiting the list of goods and services designated. This reduction may take several forms, including:

- the removal of certain goods or services;

- the explicit exclusion of sensitive or disputed segments.

Renunciation is often used to neutralise an identified risk of confusion.

One fundamental point must be emphasised:

- when the owner acts before the trademark is registered, this is referred to as a withdrawal (total or partial);

- when the owner acts after the trademark has been registered, this is referred to as a renunciation (total or partial).

This terminological distinction entails major legal consequences, particularly where proceedings are already pending.

Trademark withdrawal and opposition: a fast and regulated conflict-resolution tool

The rationale behind opposition proceedings: prevention rather than cureOnce a trademark application has been examined by the competent office and found to meet the legal requirements, it is published to allow third parties holding earlier rights to file an opposition if necessary. This enables early intervention and the resolution of disputes before the contested trademark is definitively registered.

Opposition is based on the argument that the registration of the new trademark would infringe existing rights, in particular due to a likelihood of confusion, or the reputation or renown of the earlier trademark. In this context, the total or partial withdrawal of the contested application is often regarded by trademark offices as a priority solution, as it directly alters the subject matter of the dispute.

Procedural effects of a withdrawal in opposition proceedings

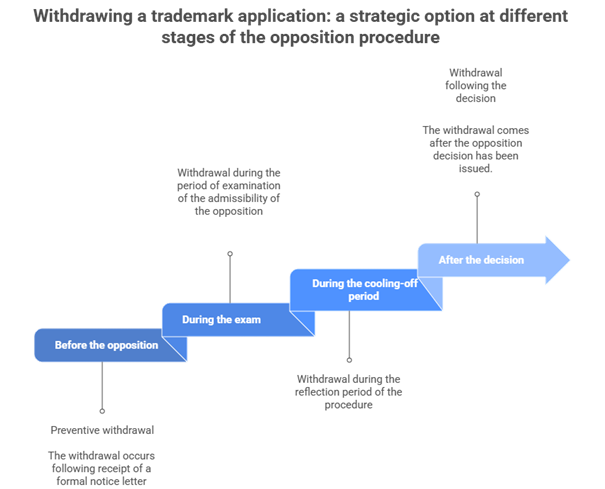

The withdrawal of a trademark application may occur at various stages of the opposition procedure. First, it may take place before an opposition is even filed, typically following the receipt of a cease-and-desist letter from the holder of earlier rights.

Withdrawal may also occur during the admissibility review of the opposition or during the cooling-off period provided for by the procedure. Finally, withdrawal may also take place after the opposition decision has been issued.

It is essential to distinguish between the effects of partial withdrawal and total withdrawal. Partial withdrawal results in an amendment of the specification of the trademark application, which then continues with this revised wording. Where the application is totally withdrawn, or where all goods or services targeted by the opposition are withdrawn, the opposition proceedings are automatically closed, as they become devoid of purpose.

This solution is highly valued by companies and practitioners, as it allows disputes to be resolved swiftly, without the need to await a decision on the merits.

Renunciation of a trademark in the context of invalidity and revocation actions: radically different legal effects

Effects and strategic implications of renunciation

Renunciation, although it does not remove the trademark from the register, results in a reduction of its scope of protection. Where renunciation is total, its effects are similar to those of a withdrawal, as the trademark is no longer protected. Where renunciation is partial, certain ownership rights are maintained, but subject to restrictions. This may create management risks, as the trademark may lose visibility or be used in a non-strategic manner.

Renunciation must be integrated into a global trademark portfolio strategy. It may help rationalise a portfolio, avoid unnecessary renewal costs and eliminate rights over trademarks that are no longer relevant. However, such decisions must be taken with caution, carefully assessing the long-term impact on the value of the trademark and the legal protection it affords.

Renunciation may also be proven necessary in a contentious context, particularly where a trademark is exposed to an invalidity or revocation action, in order to anticipate legal risk or manage the effects of ongoing proceedings.

Why renunciation does not put an end to litigation

In invalidity or revocation actions, the claimant’s objectives do not always align with the effects of renunciation:

- Invalidity or cancellation action seeks recognition that the contested trademark never met the legal conditions for valid registration and produces its effects as from the filing date.

- Revocation seeks recognition that the trademark no longer meets the legal requirements for use or that an event justifies the loss of rights, and produces its effects as from the date of non-use or the date of the request.

- Renunciation allows the owner to abandon all or part of its rights but produces effects only from the date it is recorded.

As a result, the claimant often retains a legitimate interest in pursuing the proceedings, even in cases of total renunciation.

Conclusion

Withdrawal and renunciation of a trademark are neither mere administrative formalities nor universal solutions. They are structuring legal acts, whose effects vary significantly depending on the type of proceedings involved.

While limitation of a trademark may prove an effective tool in opposition proceedings, it largely loses its relevance in the face of invalidity or revocation actions, where renunciation does not deprive the claimant of the right to obtain a decision.

A strategic, integrated and legally sound approach remains essential to preserve the value and security of trademark rights.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

Q&A

Is renunciation of a trademark definitive?

Yes. Once recorded on the register, renunciation is irreversible for the goods or services abandoned.

Can partial renunciation of a trademark affect its reputation?

Yes. Partial renunciation may give the impression that the trademark is losing relevance or use in certain sectors, potentially affecting its visibility and market perception.

Does partial or total renunciation of a trademark affect licence or partnership agreements?

Yes. Renunciation may partially or fully terminate trademark protection and therefore impact existing licence or partnership agreements, requiring stakeholders to be informed and arrangements to be adjusted.

Can a trademark that has been withdrawn or totally renounced be reused by third parties?

Yes. Once protection has been abandoned, the sign generally becomes available again, subject to any existing identical or similar earlier rights.

Is withdrawal always preferable to opposition?

No. Withdrawal is an effective and sometimes necessary tool, but it must be weighed against other strategic options, including a defence on the merits, depending on the legal and commercial stakes.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance to the public and to highlight certain issues. It is not intended to address specific situations or to constitute legal advice.