On November 4, 2025, the case Getty Images (US) Inc. v. Stability AI Limited gave rise to a highly anticipated decision of the High Court of Justice in London, stating that the use of trademarks in the context of artificial intelligence is not, in itself, unlawful. This judgment is of considerable importance for defining the scope of liability in the field of generative AI and intellectual property law.

Sommaire

Introduction

On November 4, 2025, the High Court of Justice in London delivered a long-awaited decision in Getty Images (US) Inc. v. Stability AI Limited, providing key clarifications on the interaction between generative artificial intelligence and intellectual property rights.

In particular, the Court held that the use of trademarks in the context of AI is not unlawful per se, while emphasizing that specific infringements may nevertheless be established in concrete circumstances. This ruling constitutes a significant reference point in defining the liability of generative AI stakeholders.

Background and facts of the case

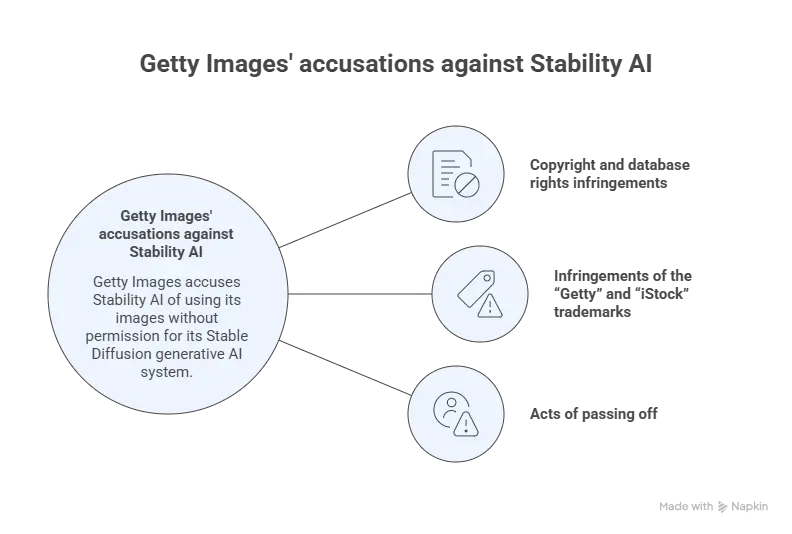

Getty Images, a leading provider of licensed images, brought legal proceedings against Stability AI, alleging that the latter had used its images to “train” its generative AI system, Stable Diffusion, a deep learning model capable of generating images from textual descriptions.

Getty Images claimed that Stability AI had used, without authorization, images from its databases to train its model and had generated synthetic images reproducing its “Getty Images” or “iStock” watermarks.

These allegations were based on three main legal grounds:

- infringement of copyright and database rights;

- infringement of the “Getty” and “iStock” trademarks, on the basis that certain generated images appeared to reproduce or evoke watermarks associated with those marks;

- acts of passing off, namely the misleading appropriation of Getty Images’ commercial reputation.

Arguments raised by the parties

Getty Images argued that Stability AI had reproduced copyright-protected works without authorization. In its view, the training process should be regarded both as an indirect reproduction of those works and as an unlawful extraction from its databases.

From a trademark law perspective, Getty Images primarily alleged infringement of its trademarks, asserting that the reproduction of its distinctive signs in AI-generated images constituted unauthorized use, likely to give rise to unfair competition, in particular by creating confusion in the public’s mind as to the existence of a license or a partnership.

Stability AI, contended under copyright law that the Stable Diffusion model neither stores nor reproduces source images, but relies on statistical learning that cannot be equated with copying protected works. It further argued that the training operations had been carried out outside the United Kingdom, thereby excluding the application of UK copyright law.

Stability AI also denied any liability, asserting that any potential infringement resulted from prompts provided by end users rather than from its own conduct.

The Court’s legal analysis

An approach based on the reality of the infringement

The Court recalled that trademark law does not sanction abstract risks, but rather actual and perceptible uses. Accordingly, the analysis focused on the images generated and disseminated, rather than on the technical training process alone.

Some images had been generated from content identifiable as originating from Getty Images, while others stemmed from broader and non-identifiable datasets. This distinction played a decisive role in the Court’s assessment.

Rejection of the copyright counterfeiting claims

With regard to copyright, the Court carried out a precise legal characterization of the disputed subject matter. It clearly distinguished between:

- the model training process, which falls within the scope of statistical learning; and

- the reproduction of protected works, which alone is capable of constituting infringement.

The Court found that Stable Diffusion does not store or contain source images in a recognizable form. The model could therefore not be treated as a medium incorporating copies of protected works within the meaning of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This conclusion was reinforced by a strict territorial analysis: as the training had been carried out outside the United Kingdom, UK copyright law was in any event inapplicable.

The Court thus drew a clear line between algorithmic learning and legally relevant reproduction, rejecting any principle-based liability of the AI provider on this ground.

Recognition of a limited trademark counterfeiting

For trademark matters, the Court adopted a more nuanced approach. It acknowledged the existence of counterfeiting, but characterized its scope as “extremely limited”.

The trademarks at issue were found to be identical or quasi-identical, and the services concerned fell within the same economic field as those covered by Getty Images’ registrations.

The judge specified that the lack of extensive evidence of actual confusion was not decisive, insofar as the likelihood of confusion could be inferred from the overall context.

Use of trademarks at the stage of generated content: consumer perception

It is at the stage of content generation and dissemination that legal risk crystallizes. The Court therefore examined the perception of the average consumer, a central concept in trademark law.

In the Getty case, several user profiles were considered:

- members of the general public using cloud-based services;

- developer users;

- users of downloadable models.

The Court held that a significant number of these users could believe that a partnership or license existed, a factor which weighed heavily in the recognition of trademark infringement.

Conclusion

The Getty Images v. Stability AI decision confirms that the use of trademarks in the AI creation process is not unlawful by nature, but may constitute an infringement of intellectual property rights where the traditional conditions of infringement are met and concretely demonstrated.

It represents an important milestone for both rights holders and AI developers, by clarifying the analytical criteria and evidentiary requirements applicable, while rejecting any blanket condemnation of generative AI.

In a context of rapidly expanding AI uses, specialized legal expertise remains essential to secure projects and anticipate litigation risks.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in anticipating and managing these emerging risks related to generative AI, integrating trademark law, data protection and emerging technologies.

Dreyfus & Associés is in partnership with a global network of intellectual property law specialists.

Nathalie Dreyfus, with the support of the entire Dreyfus firm team

FAQ

1. Can an AI system infringe a trademark without intent?

Yes. Intent is not a necessary condition in trademark law where there is use in the course of trade.

2. Is the appearance of a trademark in an AI-generated output always unlawful?

No, but it becomes problematic in cases of likelihood of confusion, damage to reputation, or parasitism.

3. Are AI developers responsible for generated images?

Case law trends towards increased accountability where outputs are commercially exploited.

4. How can trademark use by AI systems be monitored?

Through a combination of technological monitoring, legal analysis, and audits of generative platforms.

5. Can the removal of a trademark from AI outputs be requested?

Yes, through appropriate amicable or judicial proceedings, depending on the context and jurisdiction.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance and to highlight certain issues. It is not intended to address specific situations nor to constitute legal advice.