Sommaire

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Enforcing intellectual property rights without a court decision: an accepted but regulated principle

- 3 Legal limits to the extrajudicial enforcement of intellectual property rights

- 4 Allegations of infringement and abusive actions: key lessons from recent case law

- 5 Best practices for protecting rights without incurring liability

- 6 Conclusion

- 7 FAQ

Introduction

This issue is central for companies facing alleged infringements of their trademarks, patents, designs and models, or copyrights. In a context of intensified competition and rapid circulation of information, the temptation to act quickly, sometimes too quickly, is strong. Recent case law, however, firmly reiterates that the enforcement of intellectual property rights is subject to strict limits, particularly when exercised outside judicial proceedings and when it involves third parties.

Enforcing intellectual property rights without a court decision: an accepted but regulated principle

Extrajudicial action as a legitimate tool for rights protection

French law does not systematically require a prior court decision to enforce intellectual property rights.

In practice, numerous mechanisms allow for a swift response to an alleged infringement, including the sending of a cease-and-desist letter, notice-and-takedown requests addressed to online platforms, removal procedures involving technical intermediaries, or customs actions.

These measures pursue a clear economic objective: to promptly bring an allegedly unlawful practice to an end, limit damage to the value of the right, and preserve the right holder’s competitive position.

Freedom of action subject to loyalty and caution

This freedom, however, is neither absolute nor discretionary.

Case law requires that any extrajudicial action be based on a solid factual foundation, conducted with restraint, and comply with the principle of fair dealing in commercial relations. Failing this, the enforcement of rights may amount to a civil fault engaging the author’s liability.

Legal limits to the extrajudicial enforcement of intellectual property rights

The principle: prohibition of discrediting a competitor

On the basis of Article 1240 of the French Civil Code, disparagement is established whenever a company disseminates information to third parties that is likely to discredit a competitor’s products, services, or activities.

Case law is consistent: the tone used or the absence of malicious intent is irrelevant where the information disseminated has not been judicially established.

The boundary between legitimate information and abusive action

Directly informing the alleged infringer of the existence of prior rights and requesting the cessation of the disputed acts is generally accepted.

By contrast, alerting third parties—such as distributors, customers, or commercial partners—to an alleged infringement places the action in a zone of significant legal risk.

Allegations of infringement and abusive actions: key lessons from recent case law

Clear confirmation by the Court of Cassation

In a decision dated October 15, 2025 (No. 24-11.150), the Court of Cassation firmly reiterated that notifying third parties of an alleged infringement, in the absence of a court decision, constitutes an act of disparagement.

In this case, a company holding copyright in wooden wind chimes had been authorised to carry out a copyright seizure (“saisie-contrefaçon”) against a competing company and its subcontractor. Following this seizure, it sent cease-and-desist letters to several distributors of the targeted competitors, requesting that they cease marketing the allegedly infringing products.

The competing companies, considering that they had been unfairly implicated while no infringement had yet been legally established, brought an action for disparagement against the copyright holder.

At first instance, the lower courts considered that the wording of the letters sent to the resellers was measured and did not, as such, constitute disparagement. However, the Court of Cassation overturned the appellate decision, holding that “in the absence of a court decision recognising the existence of copyright infringement, the mere fact of informing third parties of a possible infringement of such rights constitutes disparagement of the products alleged to be infringing.”

Principles derived from case law

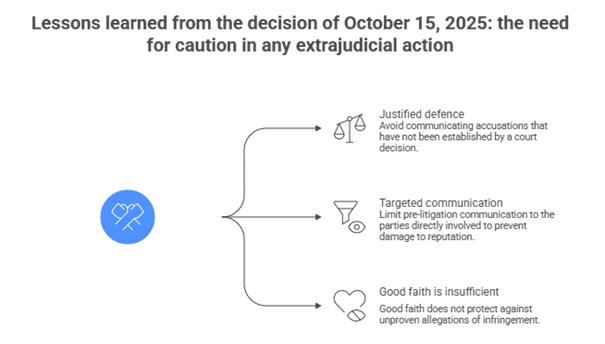

The Court thus reaffirmed three key principles governing any extrajudicial intellectual property enforcement strategy:

- The defence of rights does not justify everything: invoking an intellectual property right does not confer any entitlement to publicly disseminate unproven accusations.

- Pre-litigation communications must remain targeted: they must be strictly limited to the person suspected of infringement and must not extend to economic third parties.

- Good faith is irrelevant: even if measured, cautious and devoid of animosity, the dissemination of an unadjudicated allegation of infringement constitutes a civil fault.

Best practices for protecting rights without incurring liability

Structuring a legally secure extrajudicial action

An effective strategy is based on a graduated sequence of actions that complies with judicial requirements:

- Objectively assess the risk: evaluate the strength of the asserted rights and the reality of the alleged infringement.

- Limit exchanges to the alleged infringer: any cease-and-desist letter must be addressed exclusively to the presumed author of the acts.

- Adopt factual and proportionate wording: avoid definitive characterisations of “infringement” until recognised by a court.

- Preserve evidence: bailiff reports, seizures, and technical or comparative analyses should precede any communication.

When turning to the courts becomes essential

Where the economic risk is high or the infringement spreads through a distribution network, promptly seising a court often becomes the only secure course of action.

A judicial decision offers a dual benefit: it legitimises subsequent communications and protects the right holder against any allegation of disparagement.

Conclusion

Can intellectual property rights be enforced without a court decision? Yes, but only subject to strict limits. Case law reiterates that the defence of rights cannot justify communications liable to harm a competitor’s reputation in the absence of prior judicial recognition.

In this context, a controlled, legally framed and proportionate strategy remains essential. Anticipation and support from specialists help secure rights enforcement while preserving fair competition.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1. Is legal risk limited to litigation exposure?

No. It also includes reputational, commercial and sometimes structural risks for the company.

2. Is extrajudicial action always less risky than court proceedings?

No. If poorly handled, it may expose its author to civil liability that can be more costly than initially contemplated litigation.

3. Does good faith protect against an action for disparagement?

No. Case law considers good faith to be irrelevant.

4. Is a seizure for infringement sufficient to communicate with third parties?

No. It is an evidentiary tool, not a judicial recognition of infringement.

5. Can freedom of expression be relied upon?

It is limited by the principles of loyalty and protection against disparagement.

This publication is intended for general public guidance and to highlight issues. It is not intended to apply to specific circumstances or to constitute legal advice.