Sommaire

Introduction

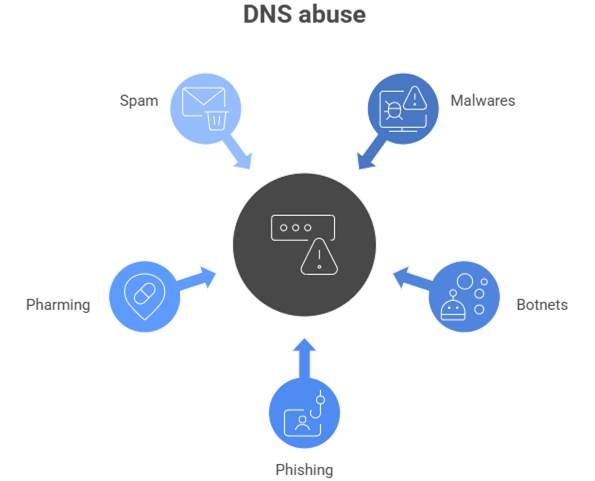

Understanding DNS abuse has become a strategic priority for companies operating online, well beyond the technical community. The Domain Name System (DNS) underpins global digital commerce, trademark visibility, and trust. Yet, it is also one of the most exploited layers of the Internet infrastructure, routinely leveraged for phishing, malware distribution, botnet coordination, and large-scale fraud.

Over the past two years, and particularly since April 2024, the regulatory and contractual landscape governing DNS abuse has undergone a structural transformation. Through reinforced contractual obligations imposed by ICANN, enhanced compliance oversight, and the launch of new policy initiatives within the GNSO, DNS abuse mitigation has shifted from best-effort cooperation to binding, enforceable responsibility.

What is DNS abuse under ICANN rules?

At the highest level, DNS abuse refers to a limited and deliberately narrow category of online harms that rely on the DNS itself to function. This scope is essential: ICANN does not regulate online content, but rather the technical coordination of the DNS.

A precise and enforceable definition

For contractual and compliance purposes, DNS abuse exists when a domain name is used to enable or materially support:

- Malware, meaning malicious software designed to compromise systems or data

- Botnets, consisting of remotely controlled networks of infected devices

- Phishing, involving deception to obtain credentials or sensitive information

- Pharming, redirecting users to fraudulent destinations through DNS manipulation

- Spam, but only when it serves as a delivery mechanism for one of the above threats

This definition draws a strict line between DNS-level abuse and content-based illegality (such as trademark infringement), which falls outside ICANN’s mandate.

DNS abuse beyond technical enforcement

Historically, DNS abuse mitigation relied heavily on voluntary cooperation and informal best practices. That model has proven insufficient against industrialized cybercrime, where abusive domains are registered in volume, activated within minutes, and rotated rapidly.

From a legal and business perspective, DNS abuse now represents:

- A direct risk to trademark integrity and consumer trust

- A source of contractual exposure for registrars and registries

- A compliance risk with measurable enforcement consequences

- A governance issue, requiring documented decision-making and accountability

In practice, DNS abuse has become a cross-disciplinary risk, sitting at the intersection of cybersecurity, contract law, regulatory compliance, and digital governance.

How did the 2024 contractual amendments change registrar and registry obligations?

ICANN’s contractual amendments, effective 5 April 2024, mark a clear shift in DNS abuse mitigation. What had long been framed as cooperative best practice is now established as a binding contractual obligation, subject to compliance review and enforcement.

Registrars: clearer duties and an obligation to act

Under the revised Registrar Accreditation Agreement, registrars must maintain accessible abuse reporting mechanisms and ensure that reports are effectively processed. Beyond accessibility, the core change lies in the explicit duty to act when presented with actionable evidence of DNS abuse involving a domain name they sponsor.

This standard does not require absolute certainty. It requires a reasonable assessment based on available information. Once met, registrars must take timely and appropriate measures to disrupt the abuse.

Registries: complementary responsibilities at the TLD level

Registry operators are subject to parallel obligations under the Base gTLD Registry Agreement. They must publish abuse contact points and, upon receiving actionable evidence of DNS abuse, either escalate the matter to the sponsoring registrar or take direct mitigation measures where appropriate.

How is DNS abuse enforced today?

Since April 2024, enforcement activity has intensified significantly. ICANN relies on:

- Third-party complaints, filed by rights holders, security researchers, or affected users

- Proactive audits and monitoring, initiated internally

- Public compliance reporting, increasing transparency and reputational pressure

Failure to comply can lead to formal breach notices and escalating contractual consequences.

Strategic implications for professional stakeholders

For legal advisers, compliance officers, and technical teams, several priorities emerge.

- Structured governance and audit-ready procedure: clear internal procedures for intake, assessment, escalation, and response are now essential. Documentation is no longer optional.

- Operational capability and staff readiness: teams handling abuse reports must understand both technical indicators of DNS abuse and the contractual standards governing mitigation.

- Proportionality and exposure to legal liability: over-reaction can be as damaging as inaction. Unjustified suspensions may expose operators to contractual disputes or liability toward registrants.

- Integrated cross-functional coordination: effective DNS abuse mitigation increasingly depends on coordination between legal, technical and compliance teams.

Conclusion

DNS abuse remains one of the most persistent threats to Internet stability and user trust. Through its 2024 contractual amendments and strengthened compliance framework, ICANN has fundamentally reshaped the expectations placed on registrars and registry operators.

For professional stakeholders, DNS abuse mitigation is now a legal and contractual obligation with tangible enforcement consequences. Mastery of this framework is essential to managing risk, ensuring compliance, and protecting digital assets in an increasingly hostile online environment.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

Q&A

What is the difference between DNS abuse and online content infringement?

DNS abuse concerns technical misuse of the DNS itself, whereas content infringement relates to what is published on a website and falls outside ICANN’s mandate.

Is spam always considered DNS abuse?

No. Spam qualifies only when it is used to deliver malware, phishing, or similar DNS-enabled threats.

Are registrars required to suspend domains automatically?

No. They must take proportionate and appropriate measures, which may vary depending on context.

Can registry operators act directly against abusive domains?

Yes, where appropriate, or they may escalate the matter to the sponsoring registrar.

Does DNS abuse mitigation create legal risk for registrars?

Yes. Both failure to act and disproportionate action can carry contractual and legal consequences.

This publication is intended for general public guidance and to highlight issues. It is not intended to apply to specific circumstances or to constitute legal advice.