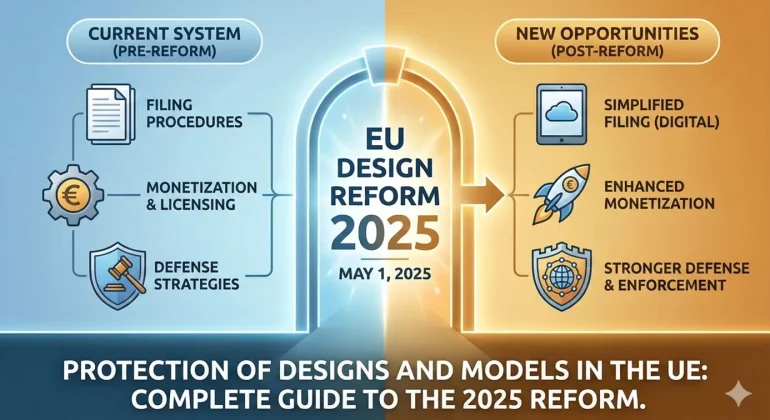

Brexit has profoundly changed the legal landscape for international franchises. Since June 1st, 2022, the European Union and the United Kingdom have applied separate exemption regimes for vertical agreements, creating new complexity for franchisors operating on both sides of the Channel. This guide details the applicable rules, the key differences between the two systems and the compliance strategies to secure your international development.

The legal framework for franchises in Europe

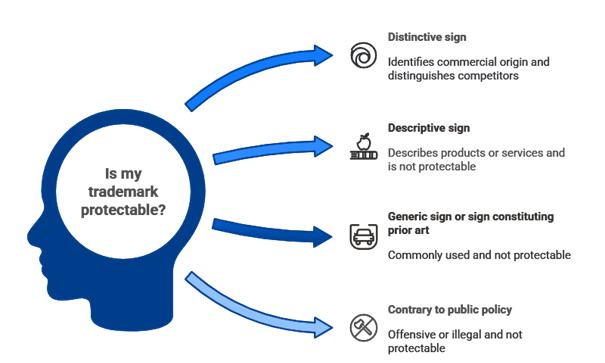

A franchise agreement constitutes a vertical agreement under competition law: it links two undertakings operating at different levels of the production or distribution chain. The franchisor grants the franchisee the right to exploit its brand, know-how and business methods, in return for a royalty and compliance with defined standards.

This contractual relationship is governed by competition rules that prohibit agreements likely to restrict competition. In the European Union, Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) sets out this principle. In the United Kingdom, Chapter I of the Competition Act 1998 serves an equivalent function.

However, certain vertical agreements may benefit from a block exemption when they generate efficiency gains from which consumers benefit. This is precisely the purpose of block exemption regulations, which create a “safe harbour” for agreements meeting certain conditions.

The legacy of the Pronuptia ruling

European franchise law has its roots in the Pronuptia de Paris v Schillgalis ruling delivered by the Court of Justice of the European Communities in 1986. This landmark decision recognized that certain contractual restrictions are inherent to the very nature of franchising and do not constitute restrictions of competition. These include clauses aimed at protecting the identity and reputation of the network, as well as the confidentiality of the know-how transferred.

This “Pronuptia test” remains relevant today: restrictions genuinely necessary to protect know-how and brand image fall outside the scope of the prohibition on anti-competitive agreements.

Regulation 2022/720: the EU exemption regime

Regulation (EU) 2022/720 on the application of Article 101(3) TFEU to categories of vertical agreements entered into force on June 1st, 2022. It replaces the 2010 Regulation and will be in force until May 31st, 2034.

This Regulation is accompanied by the Vertical Guidelines, which provide a detailed interpretation of its provisions. Together, they constitute the reference framework for assessing the compliance of franchise agreements with EU competition law.

Conditions for applying the exemption

To benefit from the block exemption, a franchise agreement must meet several cumulative conditions:

Market share threshold: both the franchisor and the franchisee must each hold a market share not exceeding 30% on their respective relevant markets. For the franchisor, this is the market on which it sells the contract goods or services. For the franchisee, it is the purchasing market that is considered.

Absence of hardcore restrictions: the agreement must not contain any of the “hardcore” restrictions listed in Article 4 of the Regulation, which cause the entire agreement to lose the benefit of the exemption.

Absence of excluded restrictions: certain clauses, although not hardcore restrictions, are excluded from the benefit of the exemption without contaminating the rest of the agreement. They must be assessed individually.

Key changes in the Regulation 2022

The 2022 Regulation provides important clarifications on several points that had been debated under the previous text:

Dual distribution: the exemption now expressly covers situations where the franchisor also sells at the same levels as its franchisees (retail, wholesale, import), provided that the agreement is non-reciprocal and the parties do not compete at the upstream level.

Information exchange: in the context of dual distribution, the exchange of information between franchisor and franchisee is subject to specific rules to avoid the risks of horizontal coordination.

Shared exclusivity: the franchisor may now designate up to five exclusive distributors per territory, compared to only one previously.

Online sales: the Regulation clarifies the permissible restrictions regarding the use of the Internet and online sales platforms.

VABEO: the UK post-Brexit regime

The United Kingdom adopted its own exemption regime with the Competition Act 1998 (Vertical Agreements Block Exemption) Order 2022, commonly known as the VABEO. Entering into force on June 1st, 2022, it will expire on June 1st, 2028, six years before the EU Regulation.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the UK competition authority, has published guidance accompanying the VABEO. This guidance diverges from the European Commission’s guidelines on certain points.

Structure of the VABEO

The VABEO broadly follows the structure of the Regulation with the same 30% market share threshold and a similar list of hardcore restrictions. However, several notable differences reflect UK competition law enforcement priorities and CMA experience.

Shorter duration: expiry in 2028 will allow the UK to adapt its regulations more quickly to market developments, but also creates uncertainty for long-term agreements.

Investigation powers: the VABEO gives the CMA a statutory power to request information from parties about their vertical agreements, strengthening its monitoring capabilities.

Key differences between the Regulation and the VABEO

Although the two regimes share a common basis, several significant divergences require separate analysis for networks operating on both sides of the Channel.

Parity clauses (MFN)

This is probably the most important difference between the two regimes.

In the UK: all wide retail parity clauses (“wide retail MFN”) constitute hardcore restrictions. A wide parity clause prohibits the franchisee from offering its products or services on better terms through any other sales channel, whether online or offline. The inclusion of such a clause causes the entire agreement to lose the benefit of the exemption.

In the EU: only wide parity clauses imposed by online intermediation services providers are excluded from the exemption, and this is an exclusion (affecting only the clause concerned) rather than a hardcore restriction (which would affect the entire agreement).

Dual distribution and information exchange

In the EU: the Regulation imposes specific conditions for information exchange between parties in a dual distribution situation to benefit from the exemption. The exchange must be directly related to the implementation of the vertical agreement and necessary to improve the production or distribution of the contract goods.

In the UK: the VABEO does not impose these formal conditions. Information exchange is exempt if it does not restrict competition by object and is “genuinely vertical”, i.e. necessary for the implementation of the vertical agreement.

Shared territorial exclusivity

In the EU: the maximum number of exclusive distributors per territory is set at five.

In the UK: the VABEO does not prescribe a maximum number but requires the number to be “determined in proportion to the territory/customer group in such a way as to secure a certain volume of business that preserves the investment efforts” of the distributors.

Post-term non-compete

Both regimes allow post-term non-compete clauses of a maximum duration of one year, limited to the premises where the franchisee operated. However:

In the EU: an additional condition requires that the clause be “indispensable for the protection of know-how”.

In the UK: the VABEO adds that the clause must “relate to goods or services which compete with the contract goods or services”.

Summary table of differences

| Criterion |

Regulation (EU) |

VABEO (UK) |

| Expiry date |

31 May 2034 |

1 June 2028 |

| Wide retail MFN clauses |

Excluded only for online intermediation platforms |

Hardcore restrictions for all |

| Information exchange (dual distribution) |

Formal conditions required |

More flexible approach |

| Shared exclusivity |

Maximum 5 distributors |

Number proportionate to territory |

| Post-term non-compete |

Indispensable for know-how protection |

Must relate to competing goods/services |

Essential franchise agreement clauses

An international franchise agreement must be carefully drafted to benefit from the exemption in both jurisdictions. Here are the main clauses to consider.

Protection of know-how

Both regimes recognize the legitimacy of clauses aimed at protecting the franchisor’s know-how. The guidelines list the types of restrictions generally considered inherent to franchising:

- Confidentiality obligation regarding the know-how transferred

- Obligation not to acquire financial interests in a competitor

- .

- Obligation to communicate improvements to the system to the franchisor

- Obligation to use the know-how solely for the purpose of operating the franchise

Non-compete clauses

Non-compete clauses are permitted under certain conditions:

During the term of the contract: the maximum duration is 5 years. Clauses that are tacitly renewable beyond this period are deemed to be concluded for an indefinite duration and do not benefit from the exemption.

After termination of the contract: the maximum duration is 1 year, and the clause must be geographically limited to the premises and land from which the franchisee operated during the term of the contract.

Territorial and customer restrictions

The franchisor may impose certain restrictions on the franchisee’s sales, including:

- Restrictions on active sales into territories or to customer groups reserved exclusively to other network members

- Obligation to operate only from an authorized place of establishment

- Restrictions on active sales into territories reserved to the franchisor

However, restrictions on passive sales (responses to unsolicited customer enquiries) are generally considered hardcore restrictions.

Exclusive sourcing

The franchisor may impose an exclusive sourcing obligation (purchasing more than 80% of requirements from the franchisor or designated suppliers) provided that this obligation does not exceed 5 years.

Hardcore restrictions to avoid

Certain clauses constitute hardcore restrictions which cause the entire agreement to lose the benefit of the block exemption. These restrictions are presumed to restrict competition by object.

Resale price maintenance (RPM)

The imposition of a fixed or minimum resale price is the most serious restriction. This includes indirect mechanisms such as:

- Fixed or maximum margins

- Discounts or reimbursements conditional on compliance with a price level

- Threats, intimidation or penalties related to pricing policy

- Minimum advertised prices (MAP) that function in practice as fixed prices

However, recommended resale prices and maximum prices are permitted, provided they do not function in practice as fixed prices.

Absolute territorial restrictions

Restrictions that completely prevent a franchisee from selling in certain territories or to certain categories of customers are prohibited. This particularly targets the partitioning of the EU internal market.

Passive sales restrictions

Restrictions on passive sales, i.e. sales resulting from unsolicited customer enquiries, constitute hardcore restrictions, with limited exceptions (notably in selective distribution systems).

Prohibition of online sales

A complete ban on the use of the Internet as a sales channel is a hardcore restriction. The franchisee must be able to sell online, even if qualitative restrictions may be imposed.

UK-specific restrictions

In the UK only, wide retail parity clauses also constitute hardcore restrictions. This stricter treatment than in the EU requires particular care when drafting contracts covering the UK market.

E-commerce and online sales

The rise of e-commerce was one of the main drivers of the revision of the exemption regulations. The new rules provide important clarifications for franchise networks.

Principle of free access to the Internet

The franchisee must be free to use the Internet to promote and sell the contract products or services. Any restriction aimed at preventing the effective use of the Internet as a sales channel constitutes a hardcore restriction.

Permitted restrictions

Certain restrictions on online sales are nevertheless permitted:

Dual pricing: the franchisor may set different wholesale prices for products intended to be sold online and those intended for in-store sales, provided that this difference is related to the different costs of each channel.

Qualitative criteria: in a selective distribution system, the franchisor may impose different criteria for online and offline sales, provided they pursue the same objectives and achieve comparable results.

Marketplace restrictions: the franchisor may prohibit the franchisee from selling via third-party marketplaces (Amazon, eBay, etc.), provided that all online presence is not prohibited.

Online intermediation platforms

The rules on online intermediation services have been strengthened. In the EU, wide parity clauses imposed by these platforms are excluded from the exemption. In the UK, the treatment is even stricter as all wide retail parity clauses are hardcore restrictions.

International compliance strategies

Franchisors operating in both the EU and the UK face an increased compliance challenge since Brexit. Several strategies may be considered.

Option 1: single contract aligned with the strictest regime

This approach involves adopting a single template contract that simultaneously meets the requirements of both the Regulation and the VABEO. Clauses are drafted according to the most restrictive standard, generally that of the UK for MFN clauses.

Advantages: simplicity of management, network consistency, reduced administrative costs.

Disadvantages: potential loss of flexibility in the EU where certain clauses would be permitted.

Option 2: separate contracts by jurisdiction

This approach involves using different contracts for franchisees established in the EU and those established in the UK, each optimized for its applicable regime.

Advantages: optimal use of the possibilities offered by each regime.

Disadvantages: management complexity, higher drafting and monitoring costs, risk of inconsistency within the network.

Option 3: modular approach

An intermediate solution involves using a common framework agreement with annexes or addenda specific to each jurisdiction. Sensitive clauses (MFN, information exchange, etc.) are addressed in these ancillary documents.

Compliance audit

Whatever option is chosen, a regular contract audit is essential. Key checkpoints include:

- Verification of market share thresholds (to be updated regularly)

- Review of non-compete clauses and their duration

- Analysis of clauses relating to online sales

- Examination of pricing mechanisms

- Review of parity and MFN clauses

- Verification of territorial restrictions

Dreyfus support for your franchise network

Dreyfus & Associés supports franchisors and franchisees in securing the legal foundations of their networks in France, the European Union and the United Kingdom.

Our expertise

Our team assists at all stages of your network development:

Audit and compliance: analysis of your existing contracts against Regulation and VABEO rules, identification of risk clauses, modification recommendations.

Contract drafting: preparation of franchise agreements compliant with both regimes, with necessary adaptations for each market. Our contracts incorporate best practices in know-how protection, intellectual property rights and competition compliance.

Brand protection: registration and monitoring of your trademarks in the EU and UK, management of opposition proceedings, anti-counterfeiting actions. The opposition procedure effectively protects your network’s identity.

Litigation: defense of your interests in disputes with franchisees, competitors or competition authorities.

Why choose Dreyfus?

Our firm stands out through:

- Recognized expertise in intellectual property law and competition law

- In-depth knowledge of the specific features of the franchise sector

- International practice with a network of correspondents in key European markets

- Nathalie Dreyfus’s accreditation as a judicial expert with the French Supreme Court and WIPO

Contact us to secure your franchise network

Frequently asked questions

What is the difference between the EU Regulation and the UK VABEO?

The VBER (Regulation 2022/720) applies in the EU until 2034, while the UK VABEO expires in 2028. The main differences concern MFN (Most Favoured Nation) clauses, the treatment of dual distribution and certain hardcore restrictions. In the UK, all wide retail parity clauses are hardcore restrictions, whereas the EU only treats those imposed by online intermediation services as such.

What clauses are prohibited in an EU/UK franchise agreement?

Hardcore restrictions common to both regimes include resale price maintenance (RPM), absolute territorial restrictions, restrictions on passive sales and a complete ban on online sales. In the UK only, wide retail parity clauses are also hardcore restrictions, requiring particular care.

What is the maximum duration of a non-compete clause?

The maximum duration of an in-term non-compete clause is 5 years. Clauses that are tacitly renewable beyond 5 years are deemed to be concluded for an indefinite duration and do not benefit from the exemption. Post-term clauses are limited to 1 year and must be geographically restricted to the franchisee’s premises.

What is the market share threshold to benefit from the exemption?

To benefit from the Regulation or VABEO exemption, both the franchisor and the franchisee must each hold a market share of 30% or less on their respective relevant markets. If this threshold is exceeded, the agreement must be individually assessed under competition law.

How to manage a franchise network covering the EU and the UK?

International franchisors must now carry out a dual compliance analysis. Two main options are available: adopting a single contract that complies with the stricter rules of both regimes, or using separate contracts adapted to each jurisdiction. A modular approach with jurisdiction-specific annexes often provides a good compromise. Regular audits and guidance from a specialised law firm are strongly recommended.

Can I prohibit my franchisees from selling on Amazon or other marketplaces?

Yes, under certain conditions. The franchisor may prohibit the franchisee from selling via third-party marketplaces (Amazon, eBay, etc.), provided that all online presence is not prohibited. The franchisee must retain the ability to sell through their own website. This restriction is permitted under both the EU and UK regimes.

What happens if my contract contains a hardcore restriction?

If your contract contains a hardcore restriction, it loses the benefit of the block exemption as a whole. The agreement must then be individually assessed to determine whether it infringes competition law. In the event of a proven infringement, the clause concerned is void and you face sanctions from competition authorities as well as damages claims from injured parties.

Can I impose resale prices on my franchisees?

No, fixing minimum or fixed resale prices (RPM – Resale Price Maintenance) constitutes a hardcore restriction under both regimes. However, you may communicate recommended prices or set maximum prices, provided they do not function in practice as fixed or minimum prices. Pressure, threats or monitoring systems aimed at enforcing compliance with these prices are also prohibited.

How long are the Regulation and VABEO exemptions valid?

The EU VBER is valid until May 31st 2034, while the UK VABEO expires on June 1st 2028. This six-year difference creates uncertainty for long-term contracts covering the UK. It is advisable to anticipate UK regulatory developments and include adaptation clauses in your contracts.

How do I calculate my market share to know if I benefit from the exemption?

For the franchisor, market share is calculated on the market where it sells the contract goods or services. For the franchisee, it is the purchasing market that is considered. The calculation must be performed annually based on turnover or, failing that, volumes. If the market share exceeds 30% but remains below 35%, the exemption may continue to apply for two additional years (only one year if it exceeds 35%).

Are online sales restrictions permitted?

A complete ban on online sales is a hardcore restriction. However, certain qualitative restrictions are permitted: website quality requirements, prohibition on selling through third-party marketplaces (while allowing a website of one’s own), or price differentiation between online and offline channels if it reflects different costs. The franchisee must always retain an effective ability to sell online.

What is dual distribution and what are its implications?

Dual distribution refers to the situation where the franchisor also sells directly to the same customers as its franchisees. This configuration is common in franchise networks. Since 2022, it has explicitly benefited from the exemption, but requires particular precautions regarding information exchange between franchisor and franchisees to avoid any risk of horizontal anti-competitive coordination.

Are post-term non-compete clauses valid?

Yes, but under strict conditions. The maximum duration is 1 year after termination of the contract. The clause must be geographically limited to the premises and land from which the franchisee operated. It must be indispensable for the protection of know-how (EU) and relate to competing goods/services (UK). A broader or longer clause does not benefit from the exemption.

Does my franchise agreement need to be notified to competition authorities?

No, there is no prior notification system. The block exemption applies automatically if the conditions are met. However, competition authorities (European Commission, CMA, national authorities) may at any time investigate an agreement and withdraw the benefit of the exemption if they find anti-competitive effects. A preventive audit by a specialized law firm is therefore recommended.

Key takeaways

- Dual regime: since Brexit, two separate systems apply (Regulation in the EU, VABEO in the UK)

- 30% threshold: the market shares of both franchisor and franchisee must not exceed this level

- Non-compete: maximum 5 years during the contract, 1 year after termination

- MFN clauses: stricter treatment in the UK (hardcore restriction)

- Online sales: cannot be completely prohibited

- Different expiry dates: VABEO expires in 2028, Regulation in 2034

Legal references