The use of a trademark on a storefront: why it does not suffice to establish genuine use of your trademark?

Introduction

At the heart of trademark law, use plays an essential role: without real exploitation, the legal protection of a trademark is at risk. But not just any use will suffice. Many right holders mistakenly believe that displaying their trademark on a storefront or window is enough to establish genuine use. European case law, particularly the K-Way decision, firmly reminds us that such practice does not meet the standards of genuine use under trademark law.

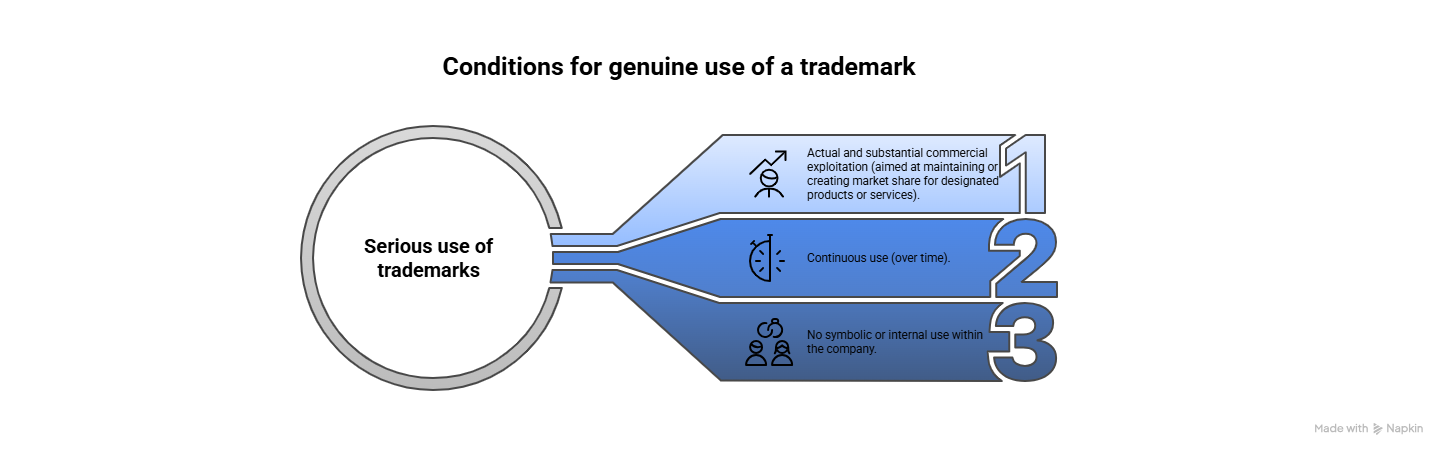

The fundamental principle of trademark maintenance: genuine use

The concept of “genuine use”

Under Article 18 of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001, the trademark holder who, without proper justification, has not made genuine use of the trademark within a continuous period of five years, starting at the earliest from the registration date, risks revocation of the trademark. This principle is reflected into French law under Article L.714-5 of the French Intellectual Property Code. The use invoked must be genuine and not merely symbolic. In other words, there must be serious and effective exploitation in the relevant economic sector, in connection with the goods or services for which the trademark is registered.

The burden of proof and its implications

The burden of proof lies with the trademark holder – not with the applicant for revocation. However, vague or incomplete evidence will not suffice: the proof must be objective, specific, and dated. Courts reject speculation or probability.

Why the use of a trademark on a storefront is insufficient to demonstrate genuine use

Legal distinction between a trade sign, a company name, and a trademark

A trade name identifies a business establishment (its façade or sales point), while a name or company name identifies, respectively, the commercial entity or the legal person. The mere presence of a trademark on a storefront shows an intention to associate the sign with the business activity, but does not ensure that consumers perceive the sign as identifying the origin of the goods or services offered.

This identification function is the essential purpose of a trademark, as established by the consistent case law of the ECJ (see Terrapin case, 22 June 1976, C-119/75 a trademark must enable consumers to distinguish goods or services as originating from one undertaking rather than another. Without a perceptible link between the sign and the goods themselves, using a trademark as a trade sign is insufficient to maintain the rights conferred by registration.

Recent case law: the K-Way decision of 25 June 2025

The reasoning of the General Court (GC)

The K-Way case (T-372/24)originated from a 2019 non-use revocation action before the EUIPO against a figurative EU trademark registered since 2006 by K-Way. The figurative trademark, consisting of a coloured rectangular band, was registered notably for goods in Classes 18 and 25 (leather goods, clothing, footwear, headgear).

In a decision dated July 11th, 2023, the EUIPO partially upheld the revocation request, cancelling the registration for all goods except outerwear and footwear in Class 25. K-Way appealed. In a decision dated May 21st, 2024 (R 1748/2023-2), the EUIPO Board of Appeal partially reversed the previous decision, finding that genuine use had been demonstrated for certain goods. K-Way then appealed again before the General Court, claiming that genuine use had also been proven for the remaining goods.

To oppose the revocation, K-Way argued that the trademark was indeed used in its mono-brand stores, where only its products were sold, and that displaying the trademark on store-front was sufficient to demonstrate genuine use for all the relevant goods. It relied on earlier case law, notably Céline SARL v. Céline SA (C-17/06), where the ECJ held that “the use of a company name, trade name, or trade sign may constitute genuine use of a registered trademark where the sign is affixed to the goods marketed, or where, even in the absence of such affixing, the use of the sign creates a link between the sign and the goods marketed or the services provided.”

The General Court acknowledged that displaying a trademark on the façade or storefront could serve as an indicator or piece of evidence in the assessment of genuine use. However, such display alone does not suffice to establish genuine use for all goods or services covered by the registration. The display of a trademark on a shopfront does not, by itself, fulfil the essential function of a trademark.

The Court accepted that the use of a trademark on a storefront may contribute to the overall evidence, but it is not in itself enough to demonstrate genuine use for all registered goods. Precise, dated, and consistent evidence must be provided, showing a direct and unequivocal link between the sign and the marketed goods or services. A presumed consumer perception or purely internal use within the company is insufficient: the use must be public, external, and commercially significant.

The fragility of trademark use evidence in mono-brand stores

The Court’s reasoning is entirely consistent with the objectives of trademark law. Indeed:

- If the owner simultaneously uses other trademarks for certain goods, the consumer’s perception of the storefront sign as identifying the specific trademark may be diluted.

- The use of a trademark as a storefront may relate only to the business premises rather than the promotion of the products themselves: if the trademark is not visible on the goods or packaging, consumers may not associate the trademark with the products.

By emphasizing these points, the Court reaffirmed that use of a trademark as a storefront or store can only serve as supplementary evidence, not as the main proof of exploitation. This approach preserves the consistency of the system by preventing trademarks from being maintained without genuine market presence for the products they claim to cover.

Conclusion

Using a trademark as a trade sign or company name can be a relevant indication of use but does not replace evidence of genuine use of the trademark in connection with the goods and services. The recent K-Way decision (T-372/24) confirms that displaying a trademark on a mono-brand store does not exempt the owner from the burden of proving use of the trademark to designate the registered goods and services. Only a comprehensive strategy combining various forms of evidence can ensure the maintenance of rights.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1. Can use of a trademark as a trade sign be invoked in a revocation action?

Yes, but it will only serve as one piece of evidence among others, never as stand-alone or genuine use.

2. What if evidence of use is not dated?

Its evidential value is significantly weakened. Courts require elements clearly situated in time and directly linked to the trademark.

3. Is use of a trademark on the Internet taken into account?

Yes, provided it is shown that the website targets the relevant market (through language, currency, or product destination) and that the trademark is used to identify goods, not merely the business itself.

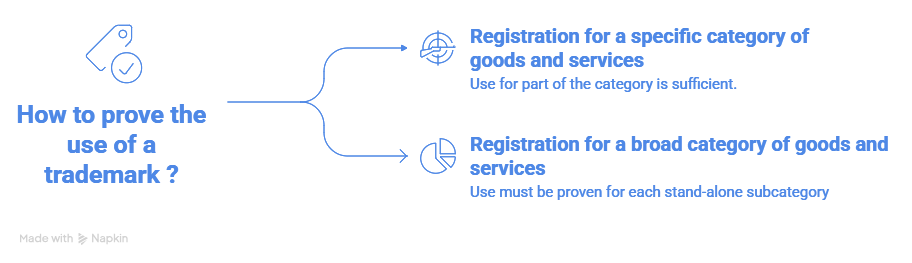

4. Can a trademark be maintained if only partial use is proven?

Yes. If the trademark is used for only some of the registered goods, protection may be maintained for those goods, but not for the others.

5. When must the trademark owner prove genuine use?

The owner is not required to prove use spontaneously, but must do so whenever a revocation action is filed or a counterclaim for revocation is raised in opposition proceedings. The proprietor must provide evidence of genuine, continuous, and relevant use during the five-year reference period preceding the filing of the action.

This publication is intended for general public guidance and to highlight issues. It is not intended to apply to specific circumstances or to constitute legal advice.