Opposition in France and the European Union: How to effectively respond to a trademark opposition?

Introduction

When an applicant receives a notice of opposition against a recently filed trademark, the stakes go far beyond a mere procedural formality. The issue concerns the protection of the company’s commercial identity, strategic positioning, and the economic value of its intangible assets. In trademark law, opposition is a specific administrative procedure allowing a third party to request the refusal of a trademark application on the grounds that it allegedly infringes earlier rights.

In this article, we will examine how an applicant can build a structured, persuasive response that complies with procedural requirements, both before the French National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO).

The legal framework of opposition in France and the European Union

Under French law, opposition is governed by Articles L.712-4 et seq. of the French Intellectual Property Code (IPC). It allows the holder of an earlier right to oppose the registration of a new trademark. The time limit for filing an opposition is two months from the publication of the trademark in the Official Bulletin of Industrial Property (BOPI).

At the European level, opposition is regulated by Articles 46 and seq. of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 on the European Union trade mark. The deadline to file opposition is three months from publication of the EU trademark application.

These time limits are non-extendable and determine the admissibility of the opposition. Any action filed out of time is automatically declared inadmissible.

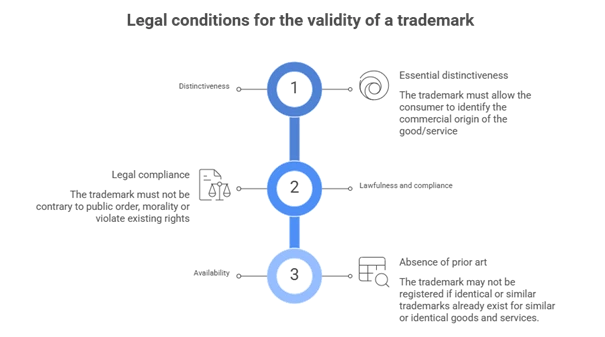

Opposition is primarily based on the existence of a likelihood of confusion, a key concept defined in Article L.713-3 of the French IPC and Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001. This mechanism does not seek to sanction infringement but to prevent the registration of a sign that could mislead the public or dilute earlier rights.

Notification of the opposition: the starting point of the defense strategy

From the date of publication in the BOPI, any person who believes that the trademark infringes on their prior rights (already registered trademark, trade name, company name, etc.) has two months to file an opposition. This period cannot be extended. If no opposition is filed within this time frame, the trademark will continue through the registration process as normal.

Within that period, it is possible to file a so-called notice of opposition and to pay the official fee, without immediately setting out the full substantive arguments: the statement of grounds (written submissions) and certain supporting documents may therefore be filed within an additional one-month period running from the expiry of the opposition time limit.

This additional period serves a practical purpose: it allows the opponent to draft and substantiate the statement of grounds (likelihood of confusion / infringement of earlier rights, etc.) after having secured the opposition deadline. That said, this subsequent filing is strictly framed: the opponent may not broaden the scope of the opposition, nor rely on new earlier rights, nor target additional goods/services beyond those identified within the initial time limit.

The notice of opposition must in any event include (Article R.712-14 of the French Intellectual Property Code):

- The opponent’s identity, together with information establishing the existence, nature, origin and scope of the earlier rights relied upon;

- Identification of the contested application, together with specification of the goods/services targeted by the opposition; and

- Evidence that the official fee has been paid.

Once the opposition has been declared admissible, the competent office proceeds notifies the applicant.Before the EUIPO, the procedure includes a specific feature: a “cooling-off” period, initially set at two months and extendable by mutual agreement between the parties. If no settlement is reached, the formal adversarial phase begins. For more information, please see our dedicated article on our blog page.

At this stage, the key issue is to determine the most appropriate strategy among several legally available options.

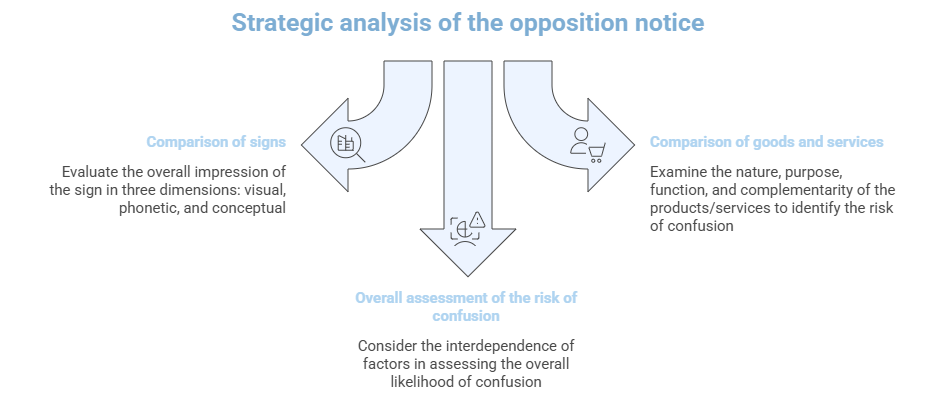

Strategic analysis of the notice of opposition

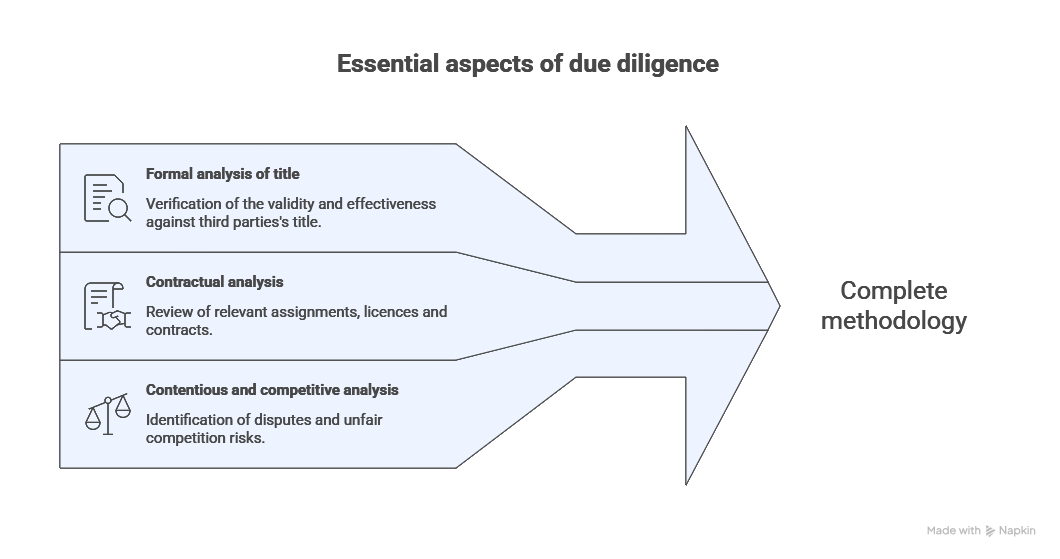

The first step for the applicant is to carefully analyze the opposition, which is based on three essential criteria:

- The comparison of the signs requires assessing the overall impression produced by the trademarks at issue. The analysis is conducted from visual, phonetic, and conceptual perspectives.

- The comparison of the goods and services focuses on their nature, purpose, function, potential complementarity, and distribution channels. Mere inclusion in the same Nice Classification class is insufficient, in itself, to establish similarity..

- The global assessment of the risk of confusion must take into account the interdependence of these factors. A low degree of similarity between the signs may be offset by a high degree of similarity between the goods and services, and vice versa.

An effective argument does not isolate a single criterion but methodically dismantles the opponent’s reasoning as a whole.

Drafting the response brief and supporting evidence

Following the analysis phase, drafting the response brief becomes a decisive strategic moment. It is not a simple formal reply but a structured legal argument aimed at clearly and convincingly demonstrating the absence of infringement of the earlier rights invoked.

The brief must first accurately recall the procedural elements: the office involved, the opposition number, the contested application reference, and the earlier rights relied upon. This contextual framework ensures that the argument is grounded in the precise legal setting.

The applicant must then set out the opponent’s arguments in order to analyze and challenge them point by point. This demonstrates a thorough understanding of the claims raised and helps identify weaknesses in the opposing reasoning. The argumentation must place the signs and goods or services within their actual economic context in order to establish the absence of confusion for the relevant public.

Finally, the brief must be supported by relevant and properly explained evidence. Proof of use, commercial documents, or market-related materials should be incorporated in a structured and reasoned manner. Overall coherence is essential: each development must serve a single objective, namely to convince the examiner that the contested mark may be registered without infringing the rights invoked.

Proof of use and alternative negotiation strategies

- Requesting proof of use: a decisive procedural lever

Where the earlier trademark relied upon has been registered for more than five years, the applicant may request that the opponent provide proof of genuine use for the goods or services invoked. This option exists before both the INPI and the EUIPO.

The burden of proof lies with the opponent, who must demonstrate real, public, and commercially justified use during the previous five years in the relevant territory.

Accepted evidence includes invoices, catalogues, advertisements, promotional materials, sales data, and contractual documents.

Use must be genuine and not merely token. In the absence of sufficient evidence, the opposition may be rejected in respect of the goods or services not properly substantiated.

This stage often represents a strategic turning point in the proceedings.

- Limiting the specification

The applicant may choose to voluntarily restrict the list of goods or services covered by the trademark application. This limitation can eliminate areas of conflict with the earlier right invoked and may lead to partial withdrawal or rejection of the opposition.

However, such limitation is definitive. It reduces the scope of protection of the trademark and must be assessed in light of future commercial exploitation plans.

In practice, this option frequently serves as a negotiation tool, particularly during the cooling-off phase before the EUIPO.

Conclusion

Responding to a trademark opposition requires technical mastery of trademark law, thorough factual analysis, and a drafting strategy aligned with the expectations of the competent offices. A response built on a solid demonstration of the absence of likelihood of confusion, supported by carefully substantiated evidence, not only neutralizes the opposition but also strengthens the legal security of your trademark.

Mastering this procedural stage is a major strategic issue for protecting your commercial identity and enhancing the value of your intangible assets.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

Q&A

1. What happens if the applicant does not respond to the opposition?

Failure to respond leads to the closure of the adversarial phase and generally results in a total or partial refusal of the application for the goods or services targeted by the opposition. Silence is treated as a waiver of the right to present arguments.

2. Can additional time be requested to prepare the response?

As a matter of principle, an extension of the time limit for filing a response is not available. Before both the INPI and the EUIPO, the time limits set for submitting observations are strictly regulated and cannot be extended upon simple request. Only specific grounds for suspension of the proceedings may be contemplated, in particular where the parties are engaged in settlement negotiations, and subject to strict compliance with the applicable procedural requirements.

3. Can an opposition be withdrawn during the proceedings?

Yes. The opponent may withdraw the opposition at any time, either as part of a settlement agreement or unilaterally. Withdrawal terminates the proceedings for the goods or services concerned. However, the opponent’s incurred costs are not automatically reimbursed. Any agreement should therefore be properly documented in writing.

4. Can new evidence be submitted after filing the response brief?

In principle, the offices set strict deadlines for the submission of evidence. Additional materials may sometimes be accepted, but their admissibility depends on the procedural stage and proper justification. Anticipating evidentiary strategy is therefore essential.

5. Can the applicant rely on good faith to overcome the opposition?

Good faith is not a decisive factor in assessing likelihood of confusion. The examination primarily focuses on an objective comparison of the signs and the goods or services. Nevertheless, evidence of prior peaceful coexistence or independent use may serve as contextual support in certain defense strategies.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance and to highlight certain issues. It is not intended to address specific situations nor to constitute legal advice.

as an

as an