Professional accounts available on Instagram: how to prevent “username squatting”?

Introduction

The launch of professional accounts on Instagram marked a decisive step in the evolution of corporate communication. Social media platforms are no longer merely channels for institutional expression; they are now fully integrated into business development strategies, customer relations, and the enhancement of intangible assets.

However, this evolution entails a specific and often underestimated legal risk : “username squatting”, namely the appropriation by a third party of a username corresponding to a trademark or distinctive sign. In a digital environment where control over identity determines credibility and visibility, securing identifiers has become a major strategic issue.

Instagram and professional accounts : a strategic asset at risk

The shift to professional accounts has significantly transformed the nature of Instagram profiles. Access to audience analytics, promotional tools and commercial features has turned the account into a genuine business asset.

In this context, the username is no longer a secondary choice. It concentrates trademark visibility on the platform and determines how easily consumers can identify and find the company. It also contributes to consistency across digital channels, including domain names and other social media platforms.

When a third party registers or exploits this identifier, the consequences go beyond mere technical inconvenience: public confusion, loss of traffic, trademark dilution and a weakening of the overall digital strategy may result.

Username squatting : definition, mechanisms and legal risks

Username squatting refers to the registration of a username identical or similar to a trademark, generally with speculative or harmful intent. This practice follows the logic of cybersquatting observed in domain names, now transposed to social networks.

Motivations may vary : resale at a high price, traffic diversion, exploitation of a trademark’s reputation, and more generally, of a company, or even identity impersonation intended to mislead consumers.

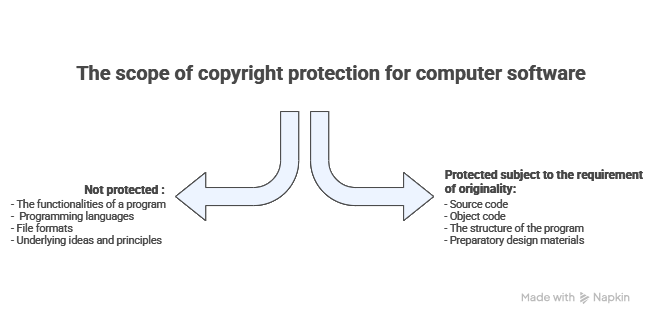

From a legal perspective, the risks are significant. Where a trademark is registered, the use of a username incorporating the protected sign may constitute trademark infringement if it amounts to use in the course of trade likely to create a likelihood of confusion. Case law acknowledges that a digital identifier may qualify as trademark use where it seeks to attract public attention in a commercial context.

In the absence of a sign being filed, action may be brought on the grounds of unfair competition or parasitism. In such cases, fault, damage and a causal link must be demonstrated, requiring a detailed analysis and solid evidentiary support.

Beyond litigation, damage to online reputation may occur rapidly and have lasting consequences, particularly where the disputed account disseminates misleading or harmful content.

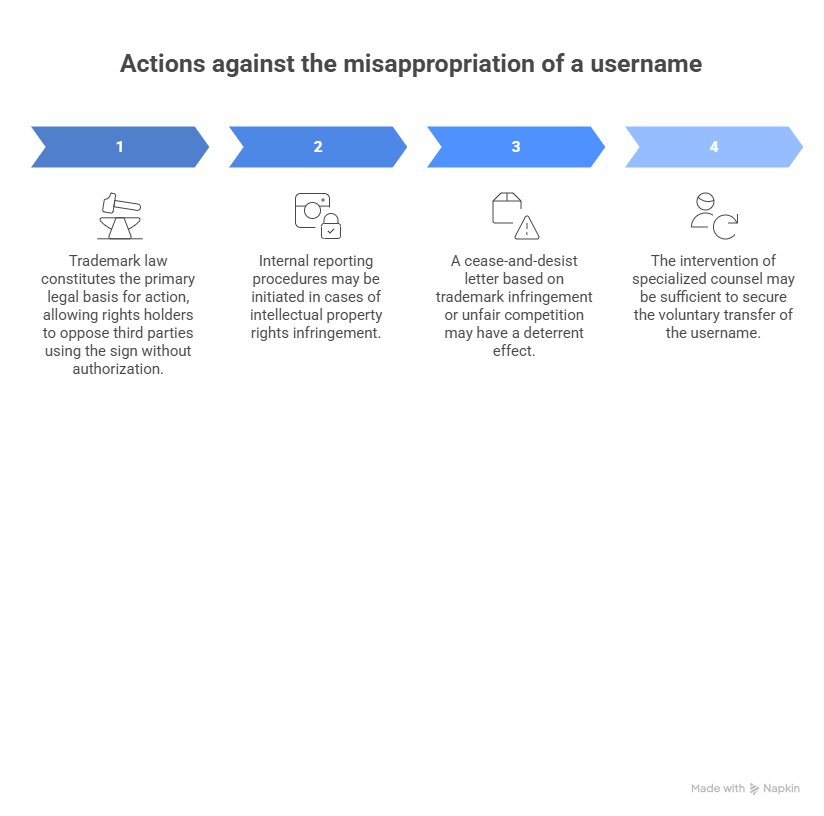

Legal grounds for taking action against the misappropriation of a username

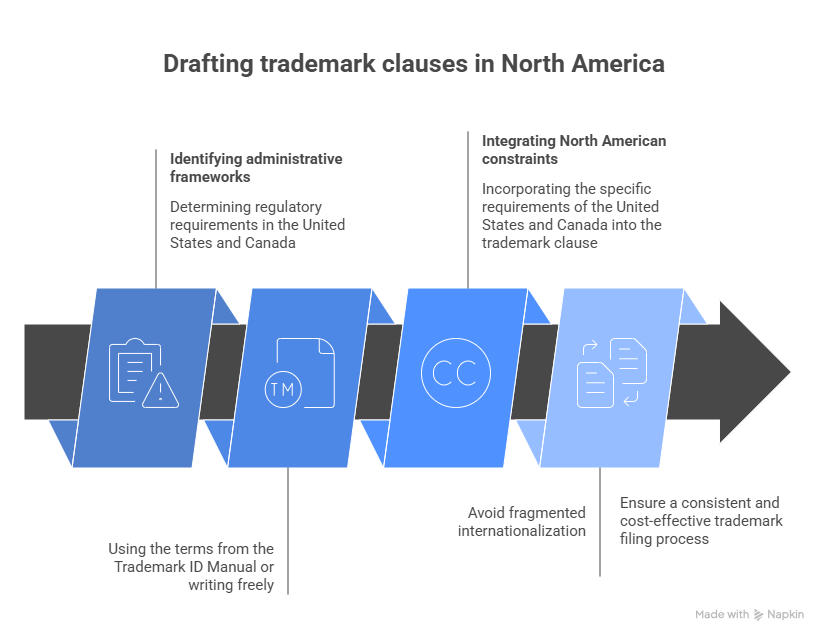

Trademark law constitutes the primary legal tool. Registration with the INPI, EUIPO, or through an international filing provides an exclusive right that may be enforced against unauthorized third-party use.

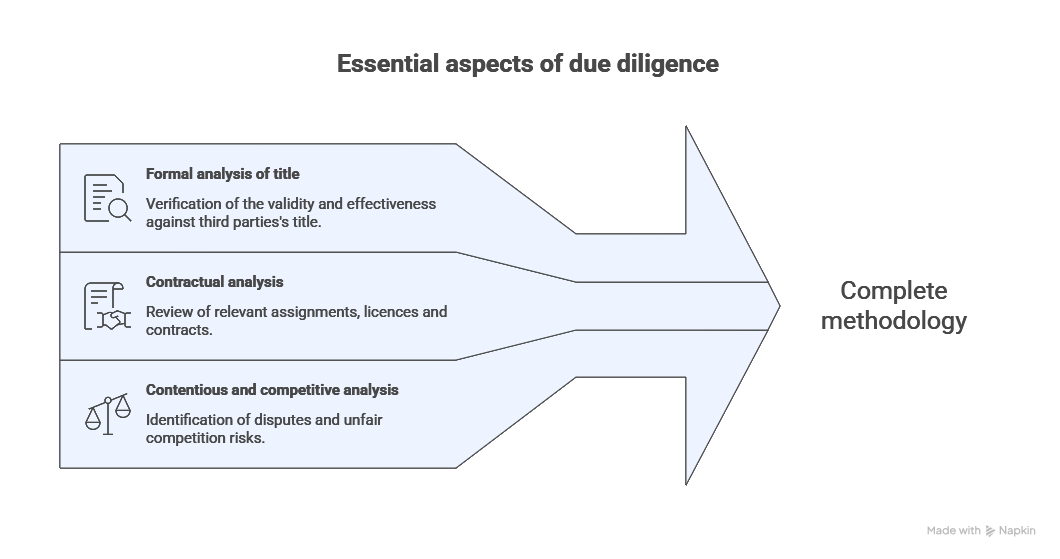

In parallel, Instagram, and more generally the Meta group, provides internal reporting procedures in cases of intellectual property infringement. These mechanisms require evidence of ownership and proof of the alleged infringement. The strength of the file and the rights holder’s responsiveness are decisive factors.

Where necessary, a formal cease-and-desist letter based on trademark infringement or unfair competition may have a strong deterrent effect. In certain cases, the intervention of specialized counsel is sufficient to secure voluntary transfer of the username.

Prevention : protecting your trademark before opening a professional account

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Reserving usernames should be integrated into any trademark launch or development strategy, alongside trademark filing and domain name registration.

Implementing digital monitoring enables early detection of abusive registrations and allows prompt action. Such monitoring forms part of a broader policy for managing intangible assets and governing digital identity.

To learn more about the importance of monitoring your trademark on social media, we invite you to read our previously published article.

A global strategic approach : digital consistency and trademark protection

Username squatting should not be viewed in isolation. It forms part of a broader reflection on the consistency and security of a company’s digital presence.

Alignment between the registered trademark, domain names and social media identifiers strengthens commercial credibility and limits the risk of impersonation. Rigorous digital identity governance helps prevent fraud, reputational damage and traffic loss.

Today, digital identity constitutes a fully-fledged intangible asset. Its protection should be approached with the same level of rigor as other intellectual property rights.

Conclusion

The launch of professional accounts on Instagram offers considerable commercial opportunities and plays a key role in corporate visibility strategies.

However, the risk of username squatting requires increased vigilance. Effective protection relies on a combination of prior trademark registration, strategic reservation of identifiers and swift action in the event of infringement.

In a competitive digital environment, securing a username is not a minor operational detail; it is a major legal and strategic issue.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property matters by providing tailored advice and comprehensive operational support for the full protection of intellectual property rights.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team.

Q&A

1. Can a company reserve a username without immediately using the account ?

Yes. Preventive reservation of a username is recommended even if the account is not immediately active. It prevents third-party appropriation and secures future digital strategy.

2. Does the inactivity of a squatted account make transfer easier ?

Not automatically. Inactivity alone is insufficient; infringement of prior rights or violation of platform rules must be demonstrated.

3. Can a slightly different username still create legal issues ?

Yes, if the similarity creates a likelihood of confusion in the public’s mind. Assessment is case-specific and depends on the trademark’s reputation and the context of use.

4. Is a username considered a company asset ?

Indirectly yes. As part of digital identity, it contributes to trademark recognition and coherence, potentially impacting the overall valuation of intangible assets.

5. Is social media monitoring truly necessary for SMEs ?

Yes. The risk of impersonation does not only affect large corporations. Appropriate monitoring enables early detection of infringements and limits their impact.

This publication is intended to provide general guidance and highlight certain issues. It is not intended to apply to specific situations nor to constitute legal advice.