How has the double proxy become the ultimate weapon of the cybersquatter?

Introduction

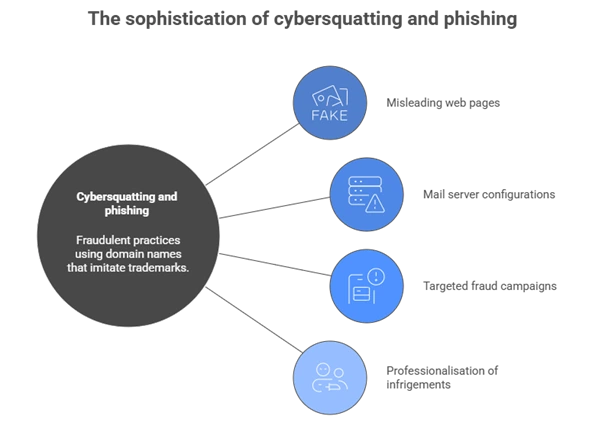

Over the past few years, the double proxy has established itself as one of the most formidable technical mechanisms used by professional cybersquatters. Behind an apparent technical sophistication hides a very concrete legal reality: an organized opacity, intended to slow down the identification of those responsible, to neutralize in practice the actions of withdrawal and to amplify infringements of trademarks, domain names and corporate reputation.

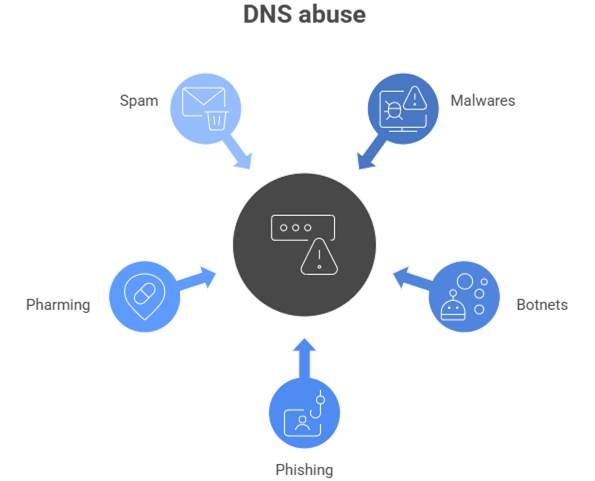

In a context of growing organized crime, the double proxy is no longer a simple tool for anonymization. It now allows the deployment of industrial phishing, employment fraud, digital counterfeiting or identity theft campaigns, designed to resist traditional legal reaction mechanisms.

Understanding the double proxy: a cascade opacity mechanism

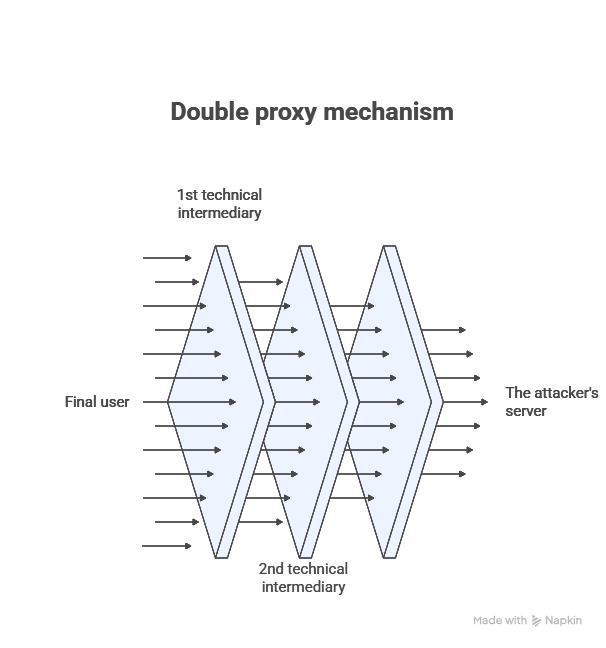

The double proxy is based on the successive interposition of several distinct technical intermediaries between the end user and the server effectively controlled by the attacker. In practice, the disputed domain name points to a first proxy, often operated by a CDN or reverse proxy provider, which then redirects to a second intermediary before reaching the final infrastructure.

These actors generally present themselves as mere technical providers and claim, in practice, the benefit of the hosting providers’ liability regime, subject to the legal qualification of their actual functions.. The objective is clear: to sever both the legal and technical link between the unlawful content and its true operator. Each layer acts as an additional screen, making the identification of the true hostng provider and the data controller particularly complex.

Fragmentation of responsibilities and enforcement actions

Unlike a simple proxy, the double proxy is based on a voluntary segmentation of technical and legal roles, which fragments the chain of responsibility and complicates any swift and coordinated action.

In practice, the chain of intermediation follows a well-established pattern. The registrar identifies a technical point of contact and refers to a CDN provider, whose official mission is to optimize the availability and performance of content. This provider then redirects to an intermediate hosting service, which is not necessarily the actual site operator. Finally, this host relies on a hidden origin server, sometimes located outside the European Union.

Each actor then presents himself as a passive intermediary and shifts responsibility to the next link in the chain. This cascading architecture exploits the grey areas of technical intermediaries’ liability law: without formally neutralizing notice-and-takedown mechanisms, it largely deprives them of effectiveness by diluting the actual knowledge of unlawful content and the capacity for immediate action.

Why the double proxy has become the cybersquatter’s ultimate weapon

The first effect of the double proxy is a systemic neutralization, in practice, of takedown procedures. Each service provider invokes their status as an intermediary, requires local court orders or redirects the complainant to another actor in the chain. A withdrawal request, although well-founded, then turns into a fragmented procedural journey, incompatible with the urgency of ongoing fraud.

The second effect is an accelerator of large-scale fraudulent campaigns. The dual proxy allows for near-instant infrastructure recycling: when a website is suspended, content is replicated elsewhere, the domain name redirected, and the proxy chain reconfigured in minutes.

Finally, this architecture leads to a dilution of legal responsibilities. Each intermediary invokes its local compliance, or lack of actual knowledge, complicating the demonstration of bad faith, which is central to cybersquatting and domain name disputes.

Impact on rights holders

The double proxy weakens the effectiveness of trademark rights and extrajudicial mechanisms. UDRP-type procedures or blocking actions carried out with registrars lose effectiveness when fraudulent content remains accessible despite the suspension or blocking of the disputed domain name.

Each additional day during which a fraudulent website remains online generates immediate economic and reputational damage, marked by a loss of customer trust and an increased risk of personal data being misappropriated.

From an evidentiary standpoint, the double proxy greatly complicates evidence gathering. The rotation of IP addresses, limited log retention and the deliberate instability of intermediation chains make the identification of the real operator particularly challenging.

What solutions are available against double proxying?

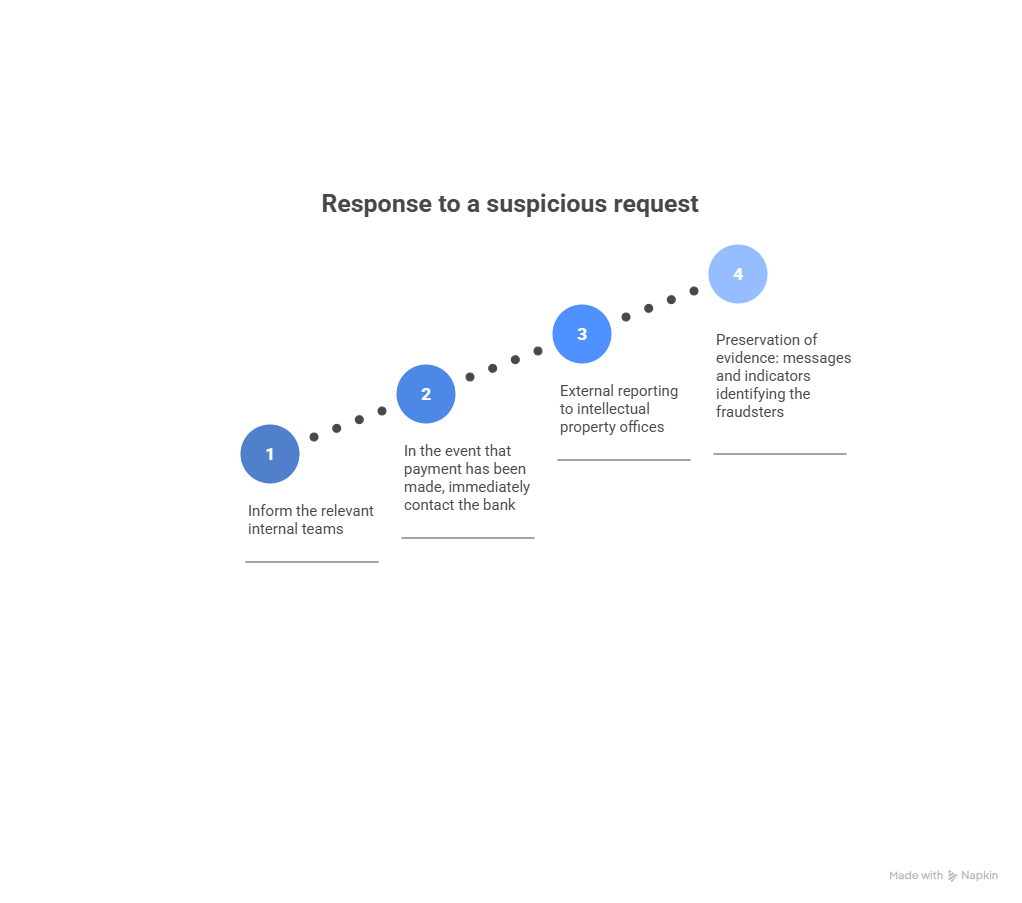

Faced with the double proxy, the effectiveness of the response relies on a multi-level legal approach. This combines coordinated notifications with the registrars, CDN providers and hosting providers, legally qualified formal notices and, where justified , targeted extrajudicial or judicial actions. The objective is to identify, within the technical chain, the actors with a concrete capacity for intervention and to avoid the dilution of responsibilities.

Anticipation through technical evidence is decisive. The precise documentation of proxy chains, time-stamped captures of redirects, dynamic DNS analysis and rapid conservation of technical elements make it possible to establish the actual role of each intermediary and to contest usefully the classification as a purely passive intermediary.

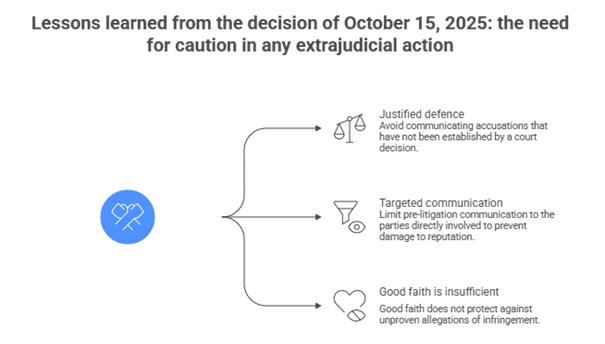

In this respect, recent case law confirms the relevance of this approach. In a judgment of October 2nd, 2025 (RG n° 24/10705) relating to a streaming fraud case, the Paris Judicial Court admitted that an infrastructure provider could be held liable as an indirect host provider, when the latter is duly notified of the illegal content and this qualification remains proportionate to its technical functions and its capacity to act.

Conclusion

The double proxy is today one of the most sophisticated and destabilizing tools of modern cybersquatting. Its impact goes well beyond technical considerations: it undermines the effectiveness of rights, the speed of remedies and user protection.

within response to this weapon, only a global strategy, combining legal expertise, technical mastery and anticipatory evidence gathering, can restore a balanced enforcement framework.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

Q&A

1. Is the use of double proxying illegal?

No. The use of a proxy, including multiple, is legally neutral in itself. It is not the technology that is unlawful, but its use. On the other hand, when double proxy is used to conceal manifestly unlawful activities, it constitutes a strong indicator of bad faith in the overall legal analysis.

2. Can an intermediary be forced to keep their logs?

In principle, not without judicial intervention. Data retention obligations are strictly regulated. On the other hand, rapid precautionary measures may be requested in order to avoid the automatic deletion of essential technical data.

3. Does the use of non-EU servers prevent any legal action?

No, but it complicates enforcement. It often requires combined actions (administrative, judicial) and more frequent reliance on international assistance or actors located upstream in the technical chain.

4. Are automated detection tools effective against double proxy?

They are useful but insufficient alone. They must be combined with legal and technical analysis, capable to interpret redirections, infrastructure structures and weak signals.

5. Is a website protected by a CDN necessarily suspicious?

No. CDNs are widely used for legitimate purposes. It is the combined use of several layers of proxy, associated with unlawful content, that may become problematic.

6. Are the hosting providers always able to act quickly?

Not necessarily. Some intermediaries have only partial control over the infrastructure and must themselves turn to other providers before they can intervene.

The purpose of this publication is to provide general guidance to the public and to highlight certain issues. It is not intended to apply to particular situations or to constitute legal advice.