Legal definition, recent case law, litigation procedures, evidence methods and protection strategies — everything you need to know to protect your confidential information.

In an economy built on intangibles, a company’s value often lies in what it doesn’t disclose. Customer databases, algorithms, business strategies or technical know-how: these critical assets are not always patentable, and this is where trade secret protection comes into play.

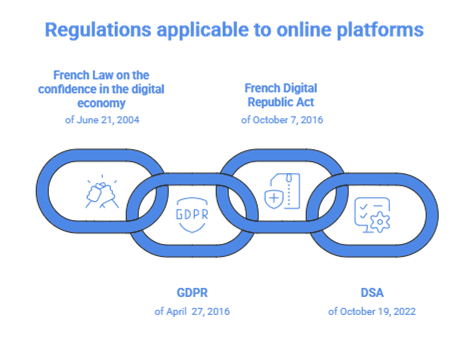

Since the French law of July 30, 2018, transposing EU Directive 2016/943, France has had a powerful but demanding protective framework. The 2024-2025 case law has significantly clarified the relationship between trade secrets, the right to evidence and GDPR. This reference guide provides everything you need to understand, protect and defend your confidential information.

This guide covers:

- The legal definition and 3 cumulative protection criteria

- The 2024-2025 case law review and its practical implications

- Litigation procedures: taking legal action, timelines, costs

- Methods for proving the prior existence of your secret

- Industry case studies (pharma, tech, food & beverage)

- Coordination with other intellectual property rights

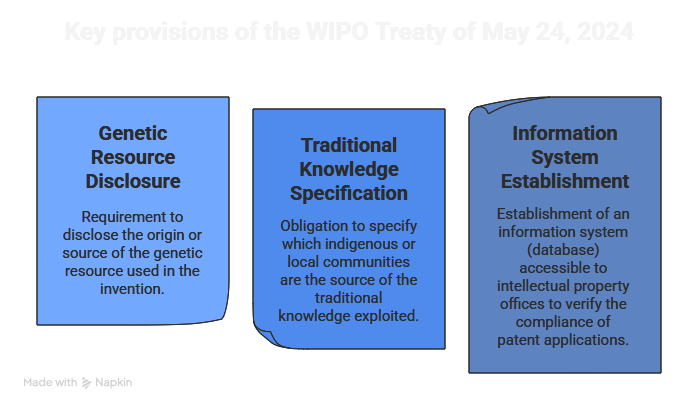

- The international dimension of protection

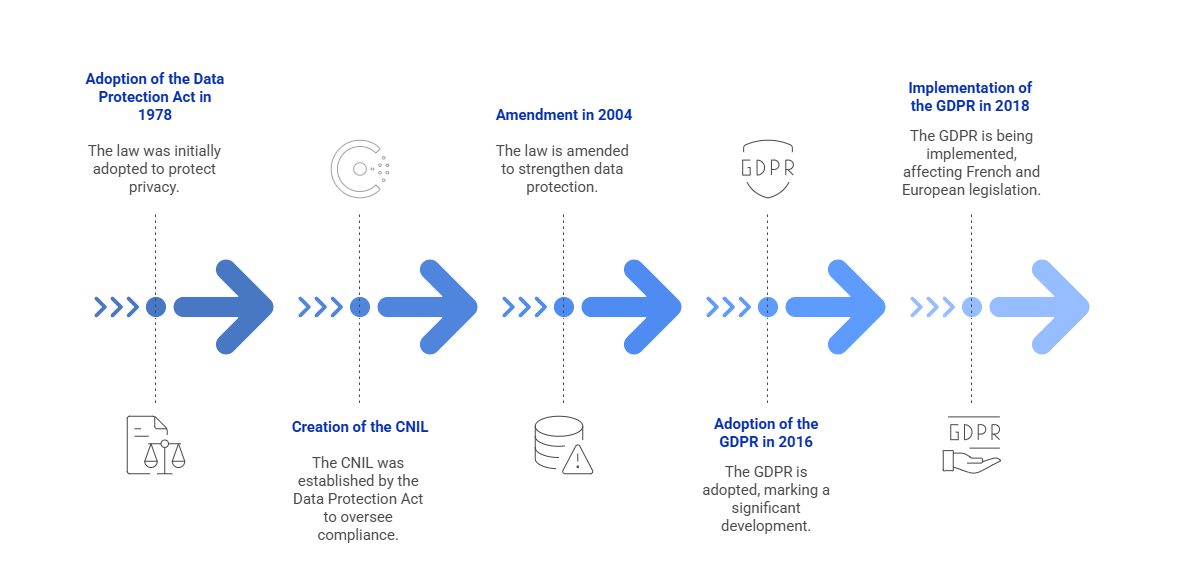

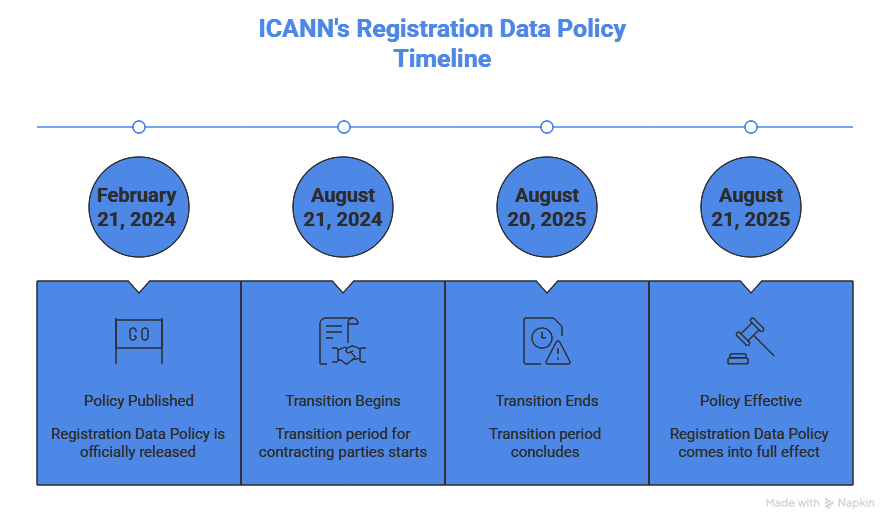

Evolution of the Legal Framework

| June 8, 2016 |

Adoption of EU Directive 2016/943 on trade secret protection |

| July 30, 2018 |

Transposition into French law (Law No. 2018-670) |

| December 22, 2023 |

Cass.Ass: admission of unfairly obtained evidence under conditions (No. 20-20.648) |

| June 5, 2024 |

Cass. Com.: first articulation between right to evidence / trade secrets (No. 23-10.954) |

| February 5, 2025 |

Cass. Com.: confirmation of the “indispensable” requirement (No. 23-10.953) |

| February 27, 2025 |

CJEU: GDPR prevails over trade secrets for automated decisions (C-203/22) |

1. Fundamentals: What is a Trade Secret?

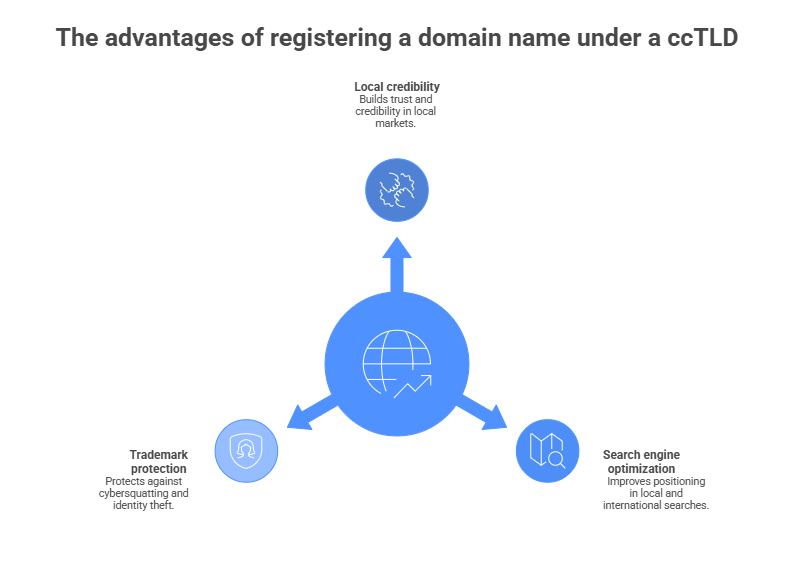

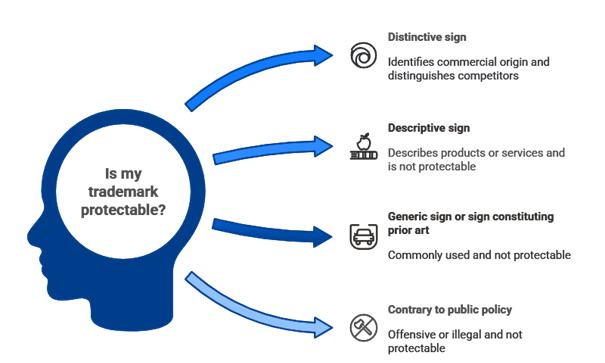

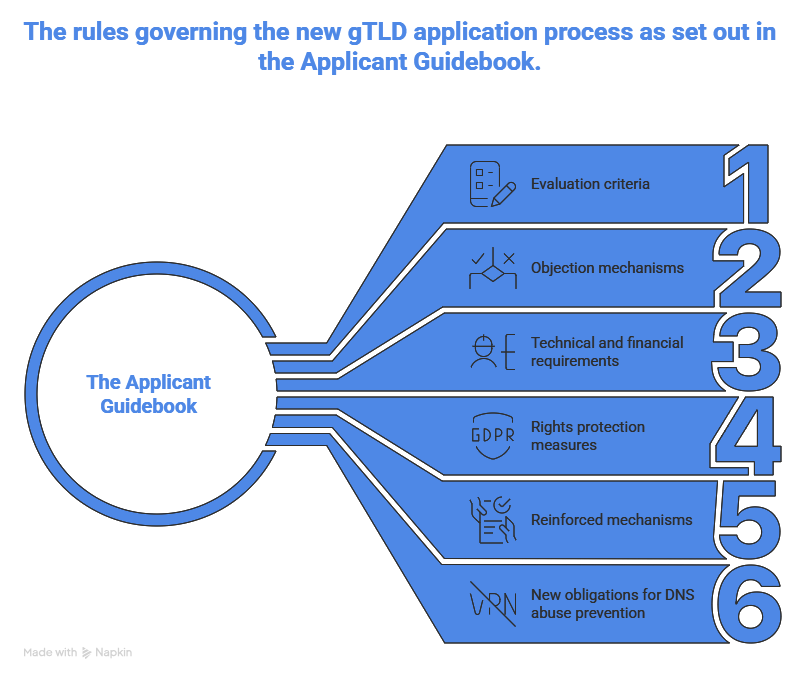

Unlike traditional intellectual property (patents, trademarks) which relies on a public title, trade secret law protects information by virtue of it remaining secret. This protection arose from a simple observation: some strategic information cannot or should not be patented.

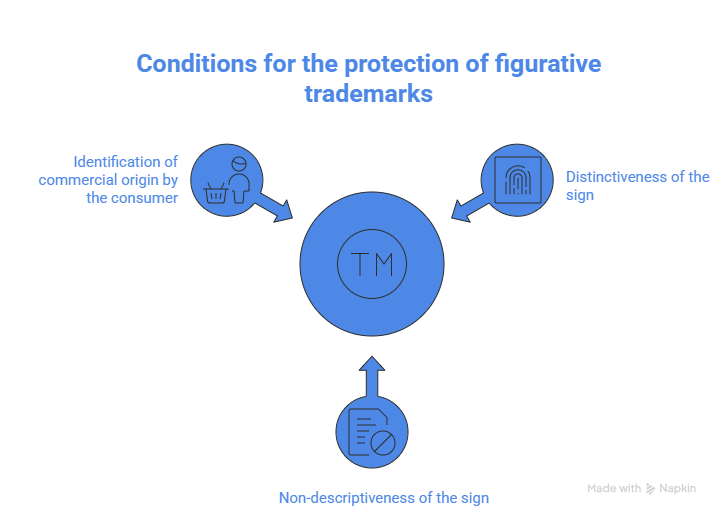

The Legal Definition (Article L.151-1 of the French Commercial Code)

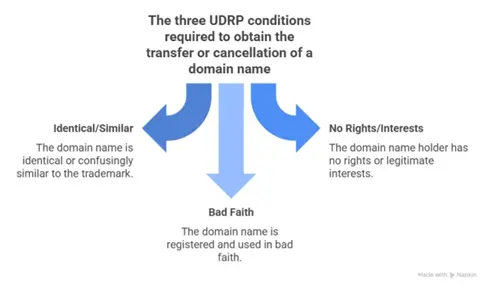

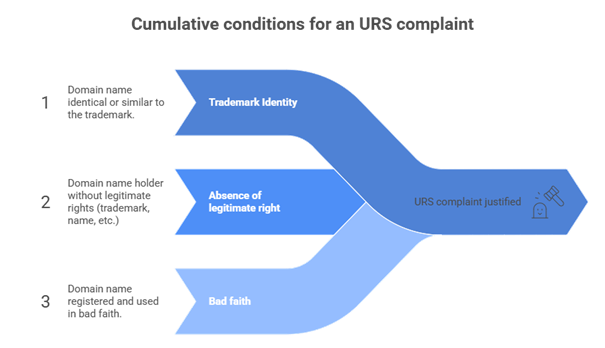

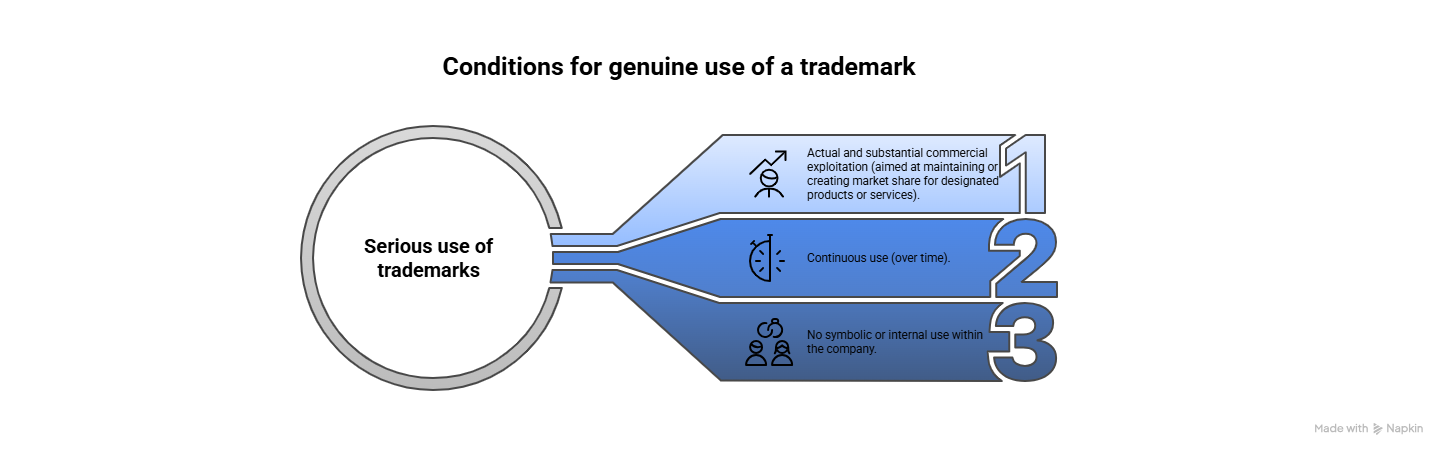

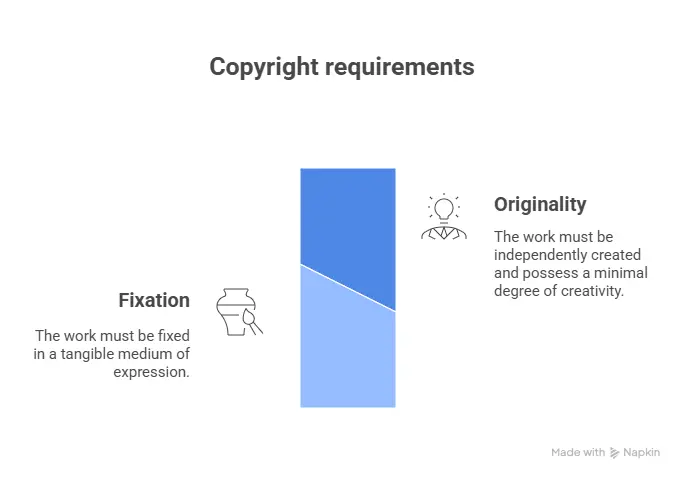

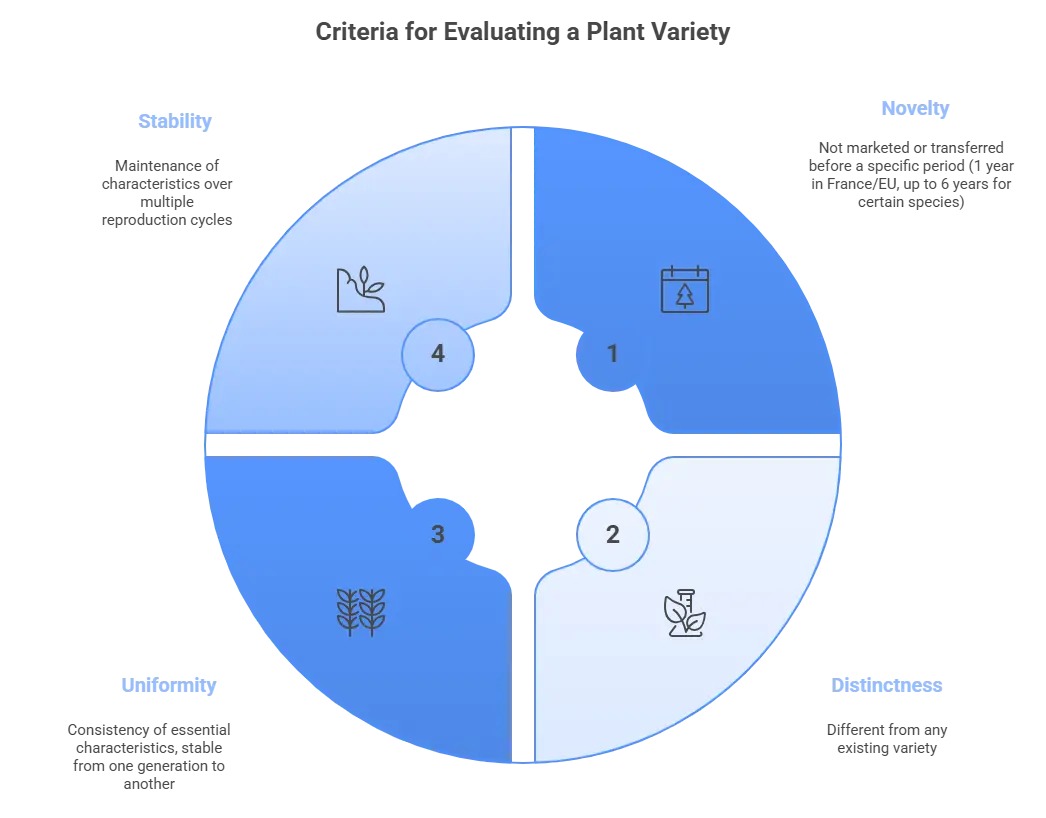

To be protected by law, information must cumulatively meet three strict criteria:

The 3 Cumulative Conditions

- Secrecy

The information is not generally known or readily accessible to persons within circles that normally deal with this type of information. This is the “non-obviousness” criterion: the information must not be commonplace in the relevant sector.

- Commercial Value

The information has commercial value (actual or potential) precisely because it is secret. This value can be direct (competitive advantage) or indirect (cost avoidance).

- Reasonable Protection Measures

The information is subject to concrete protection measures by its holder to maintain its secrecy. This is often the determining criterion in litigation.

Essential Point

If you don’t actively protect your information (confidentiality clauses, passwords, document classification), courts will consider there is no trade secret. This is the criterion most often neglected by companies.

What Does Trade Secret Law Cover?

The scope is very broad. The concept of “information” is interpreted extensively and includes:

Technical know-how: manufacturing processes, recipes, chemical formulas, production methods, optimization parameters, technical drawings.

Commercial information: customer and prospect lists, pricing policies, supplier terms, product margins, internal market shares.

Strategic data: M&A projects, development plans, proprietary market studies, business plans, financial projections.

Organizational information: strategic organization charts, management methods, optimized internal processes.

Algorithms and data: source code, scoring models, proprietary databases, software architectures.

What Trade Secret Law Does NOT Protect

Understanding the limits of this protection is essential:

Independent discovery: if a competitor independently develops the same information, you cannot sue them.

Lawful reverse engineering: analyzing a product placed on the market to understand how it works is legal (unless contractually prohibited).

Information becoming public: once a secret is disclosed (voluntarily or not), protection is lost definitively.

General employee skills: the know-how acquired by an employee (their “experience”) belongs to them and can be used with a new employer.

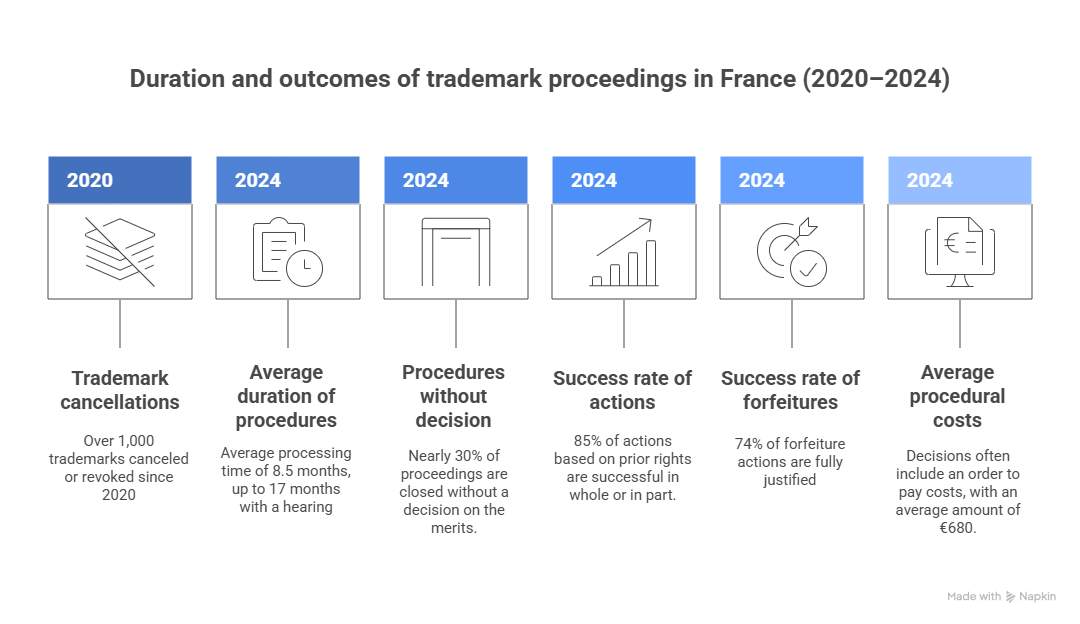

2. 2024-2025 Case Law Review

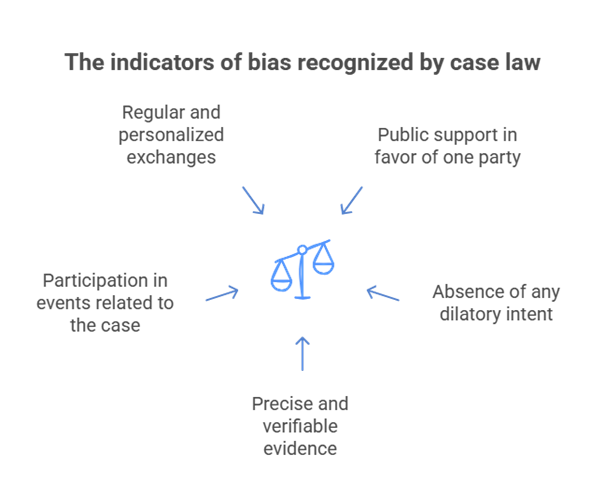

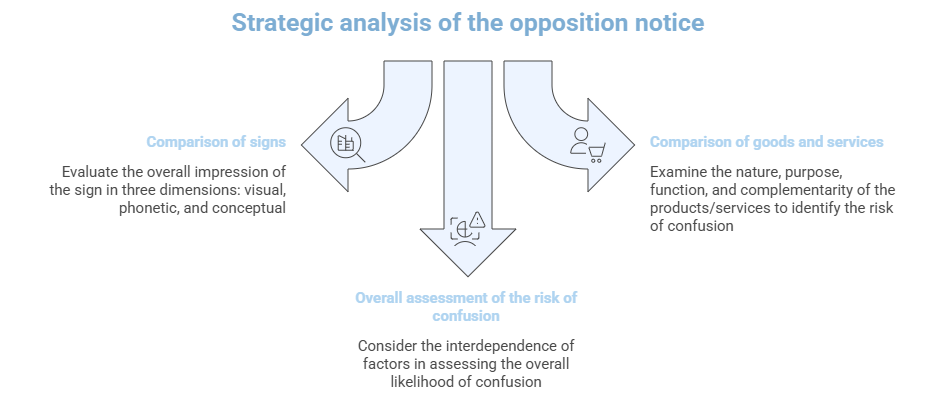

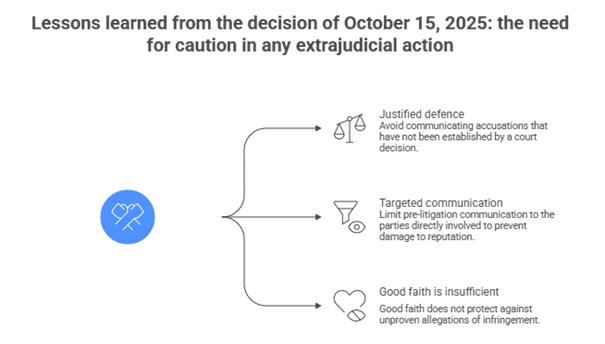

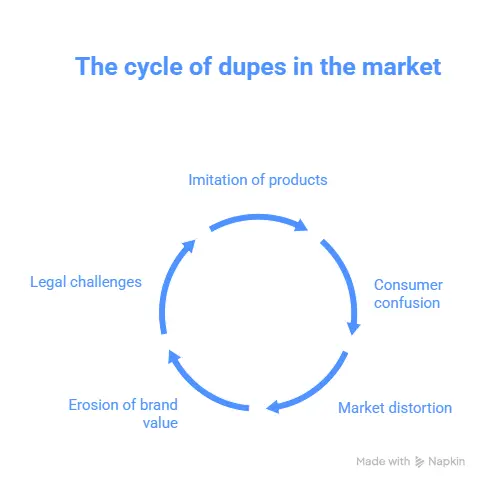

Recent judicial developments have been marked by an ongoing tension between two imperatives: protecting business secrets and the right to evidence (a party’s need to obtain documents to assert their rights in court).

The Landmark Ruling: Cass. Com., February 5, 2025 (No. 23-10.953)

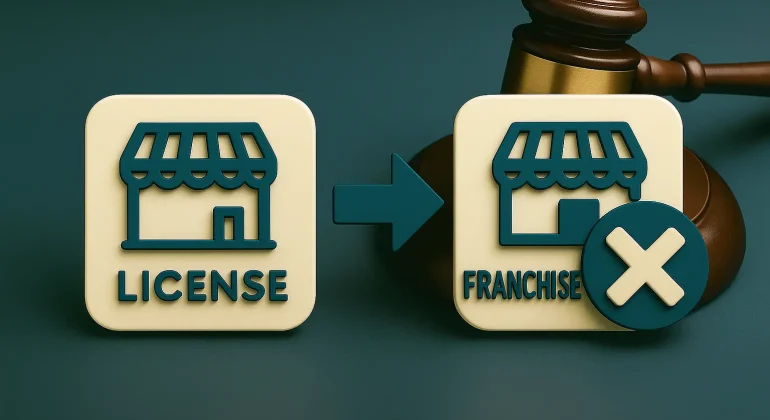

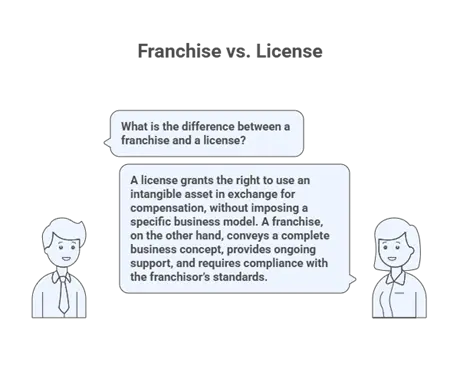

This was the major turning point. In a case between the franchise networks Speed Rabbit Pizza and Domino’s Pizza, the French Cour de Cassation established a structuring principle for balancing these rights.

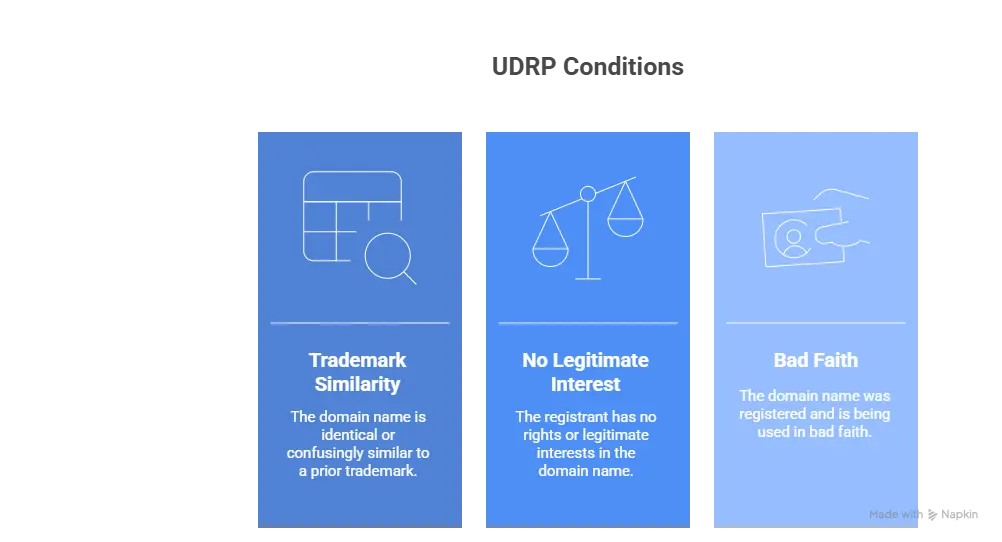

The Legal Principle

“The right to evidence may justify the production of elements covered by trade secrets, provided that such production is indispensable to its exercise and that the infringement is strictly proportionate to the aim pursued.”

Practical implications:

For a judge to order production of a document covered by trade secrets, it must be indispensable to resolve the dispute, not merely “necessary” or “useful”. The term “indispensable” is intentionally restrictive: it excludes “fishing expedition” requests (exploratory evidence gathering).

The judge must conduct a proportionality assessment between the competing rights. This involves verifying that no less intrusive means of proof exists, and that the requested document is truly decisive for the outcome of the case.

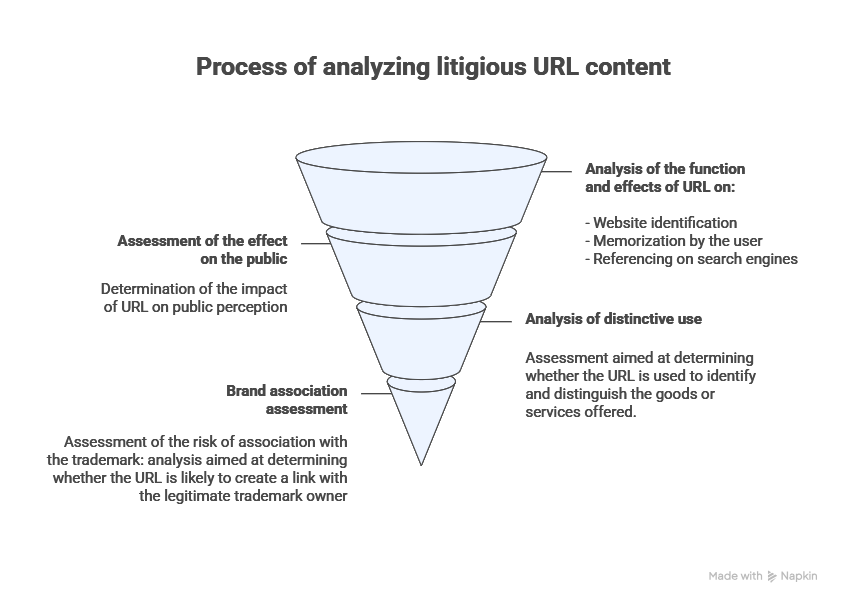

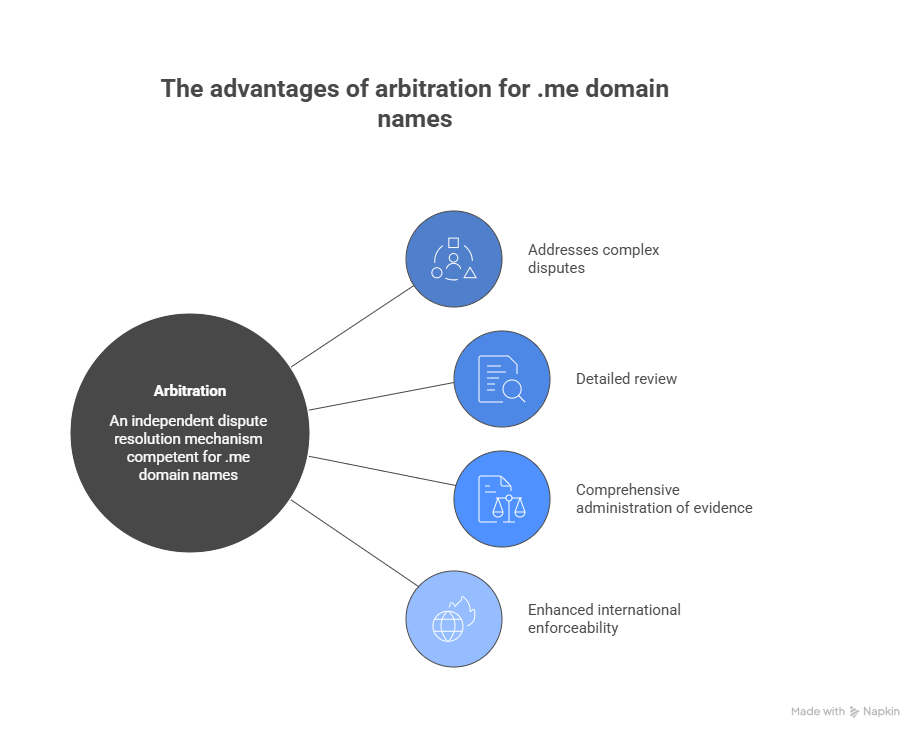

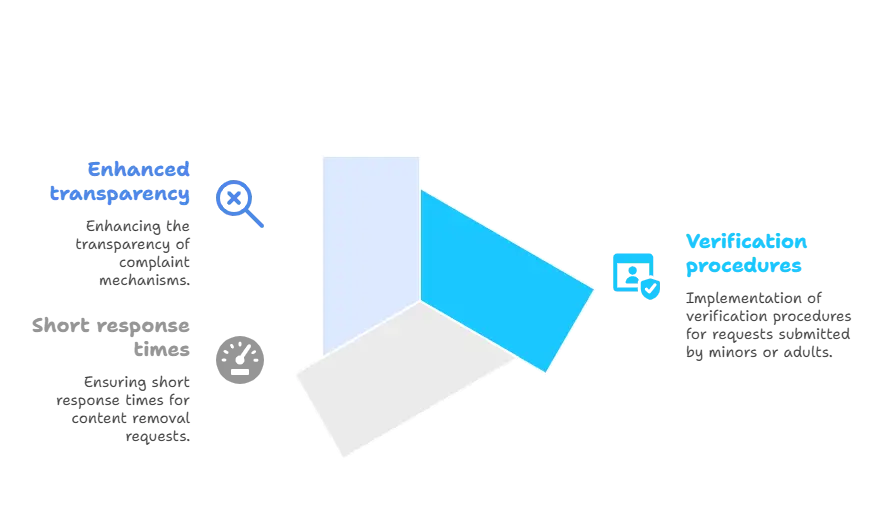

Managing Seizures (Seizure-Infringement and Article 145 CPC)

When a company is subject to an ex parte seizure on its premises, how can it prevent its secrets from ending up with a competitor?

Case law requires strict application of provisional sequestration:

Documents seized that may violate trade secrets are placed in escrow with a third party (usually the bailiff). A period of one month is granted to the seized party to contest disclosure. The judge rules on whether documents can be communicated before any transmission to the seizing party, applying the proportionality test.

The Preparatory Ruling: Cass. Com., June 5, 2024 (No. 23-10.954)

This decision laid the groundwork for the balance, recognizing for the first time that the right to evidence could justify an infringement of trade secrets, while requiring strict judicial oversight.

Unfairly Obtained Evidence: Cass.Ass, December 22, 2023 (No. 20-20.648)

The French Cour de cassation ruled that evidence obtained unfairly (secret recordings, stolen documents) may be admitted in court if two conditions are met: production is indispensable to exercising the right to evidence, and the infringement of the opposing party’s rights is proportionate to the aim pursued.

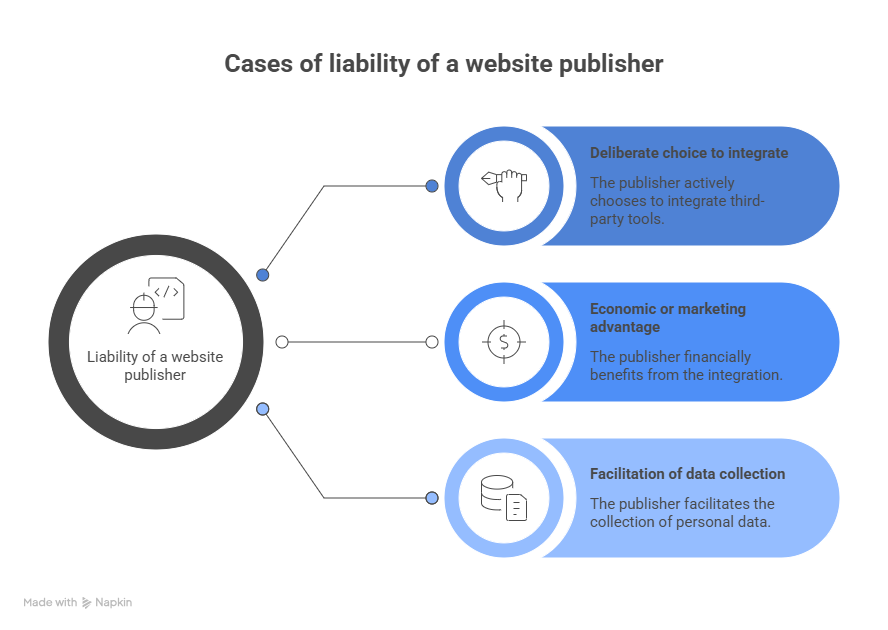

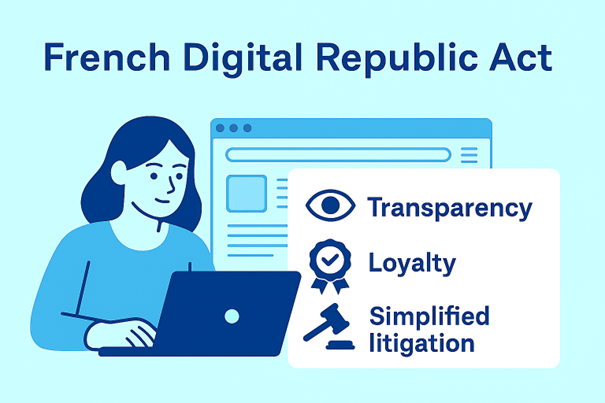

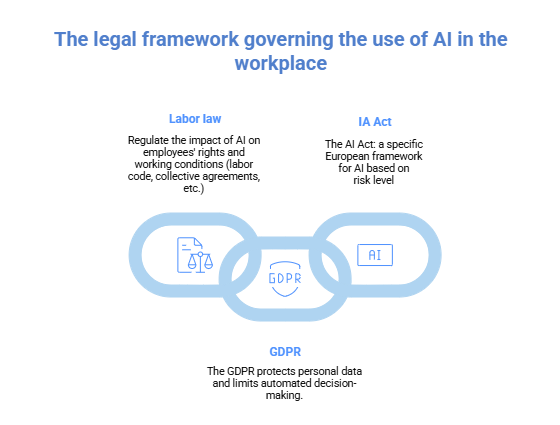

3. Trade Secrets vs GDPR: The CJEU Ruling of February 27, 2025

At the European level, the Court of Justice (CJEU, C-203/22, Dun & Bradstreet Austria) issued a major decision on the relationship between trade secrets and individual rights.

The Facts

An Austrian consumer was denied a mobile phone contract on the grounds of insufficient creditworthiness. This refusal was based on an automated assessment (credit scoring) conducted by Dun & Bradstreet. She requested an explanation of the “underlying logic” of this decision, invoking Article 15 of the GDPR (right of access). The company refused, citing trade secret protection of its algorithm.

The CJEU Decision

Principle Established by the CJEU

GDPR prevails over trade secrets regarding the right of access to personal data and information about automated decisions. The data controller must provide “meaningful information about the logic involved” in a manner that is “concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible”.

What this means for businesses:

Simply providing an algorithm or complex mathematical formula is not sufficient to fulfill the information obligation. The explanation must be understandable to a non-specialist.

The company must enable the individual to understand what data was used and how it influenced the decision. This doesn’t mean disclosing the complete algorithm, but explaining the determining criteria.

In case of dispute, allegedly protected information must be communicated to the judge who will balance the competing rights.

Sector Impact

This decision directly affects sectors using automated scoring: banks and credit institutions, insurance (personalized pricing), recruitment (automated CV screening), real estate rental (tenant creditworthiness), and more generally any automated decision-making process with significant effects on individuals.

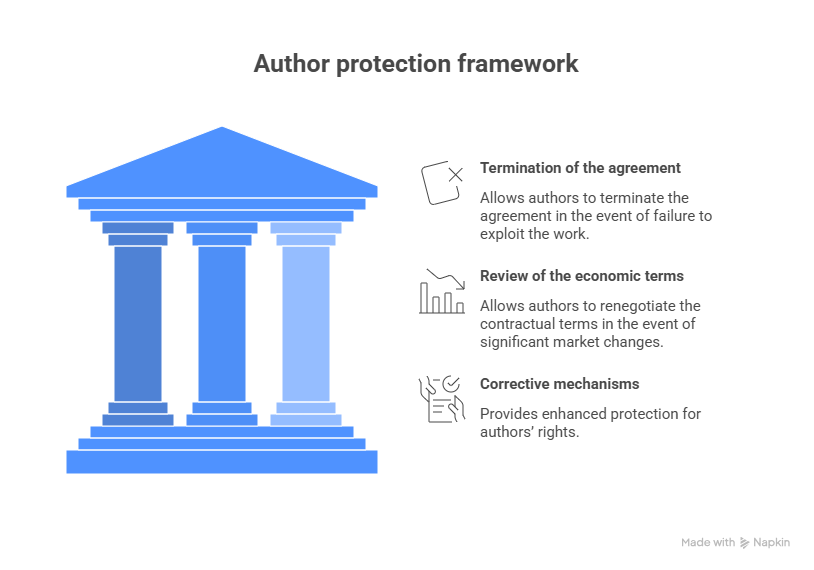

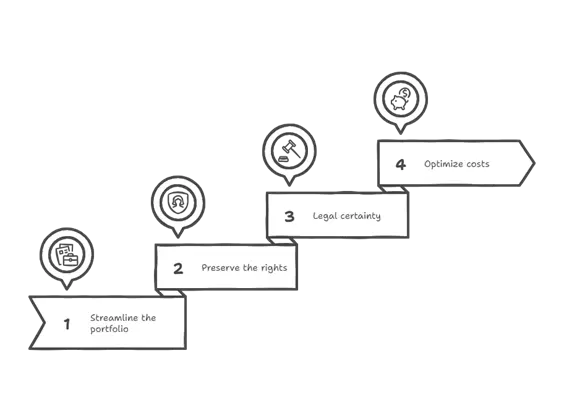

4. Protection Strategies: “Reasonable Measures”

To benefit from legal protection, a company must prove it has implemented concrete measures. The term “reasonable” means appropriate to the nature of the information, the size of the company and the economic context. A SME doesn’t have the same resources as a Fortune 500 company, and courts take this into account.

Protection Measures Checklist

Legal Measures

- ☐ Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs): systematic before any discussion with a partner, service provider or investor

- ☐ Enhanced confidentiality clauses: in employment contracts and commercial agreements

- ☐ Non-compete clauses: for strategic positions, within legal limits

- ☐ IT charter: explicitly mentioning confidentiality duties and signed by all employees

- ☐ Internal regulations: incorporating confidentiality obligations

Technical Measures

- ☐ Access management: “need-to-know” principle

- ☐ Traceability: access logs for sensitive documents

- ☐ Encryption: of sensitive data at rest and in transit

- ☐ Strong authentication: MFA for access to critical systems

- ☐ DLP (Data Loss Prevention): data leak prevention tools

Organizational Measures

- ☐ Document marking: “CONFIDENTIAL — TRADE SECRET” label on sensitive documents

- ☐ Information classification: confidentiality level system (C1, C2, C3…)

- ☐ Staff training: awareness of social engineering risks and information leaks

- ☐ Exit procedures: reminder interview about obligations, retrieval of access and documents

- ☐ Physical security: secured premises for sensitive paper documents

- ☐ Secret inventory: regular mapping of the company’s confidential information

Practical Tip

“CONFIDENTIAL” marking of documents is the simplest and most effective measure to prove in court. An unmarked document will be difficult to consider as a trade secret. Also invest in traceability: being able to demonstrate who accessed what information and when is invaluable in litigation.

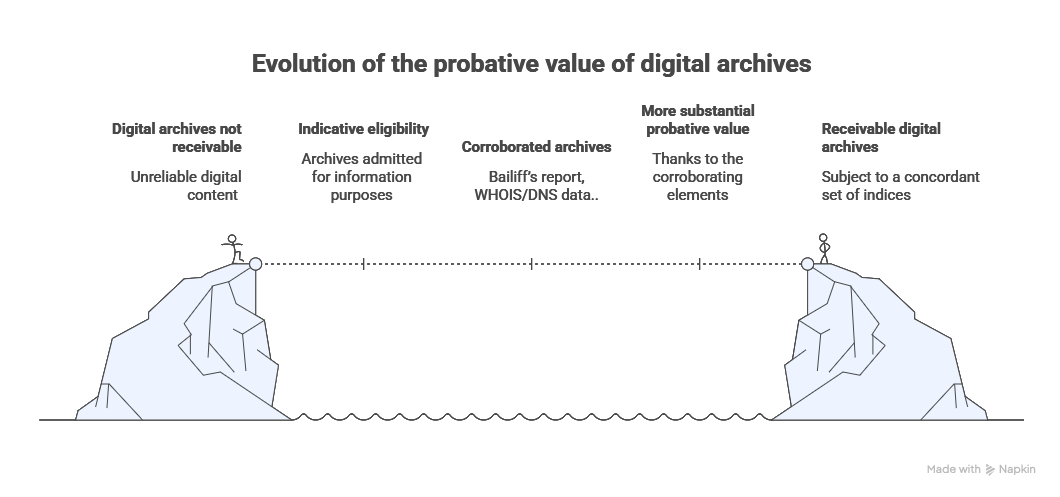

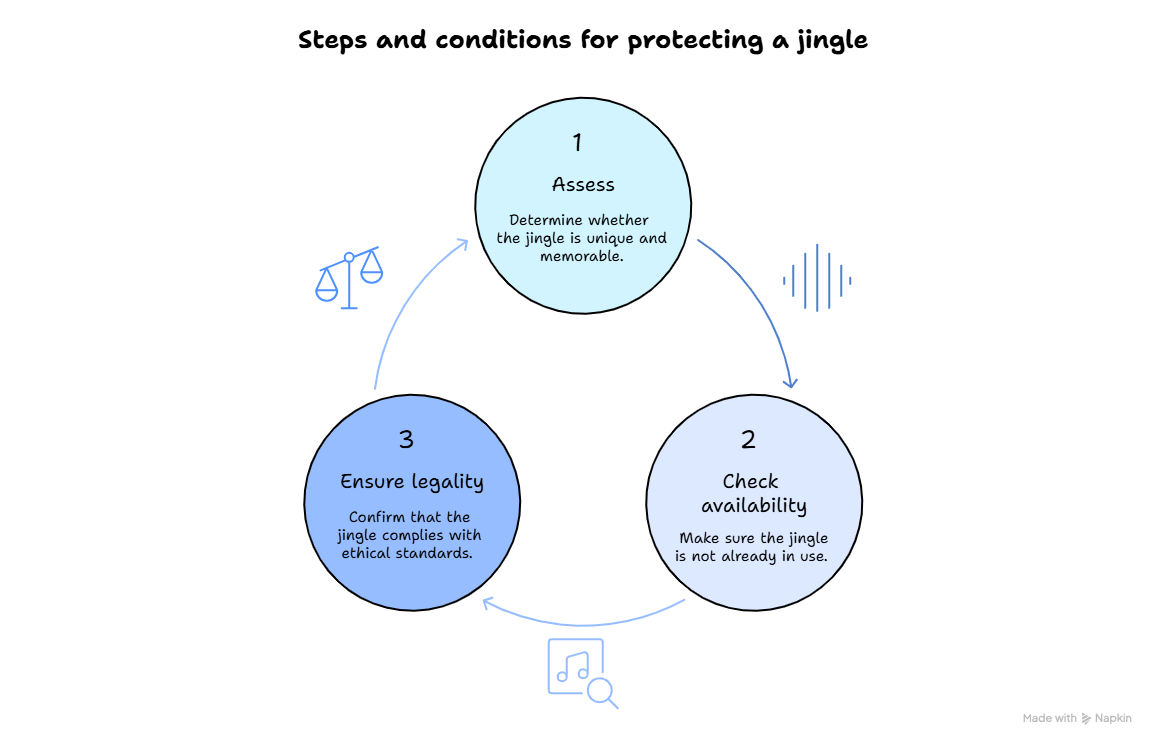

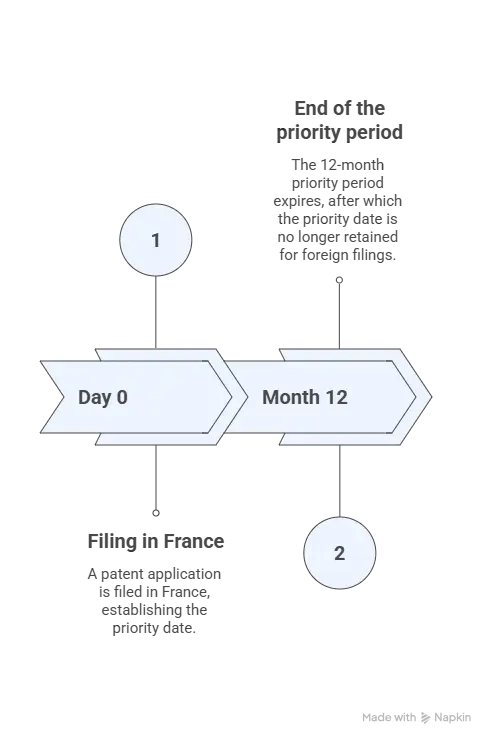

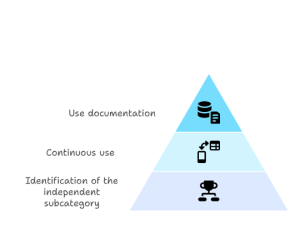

5. Proving Your Secret: Timestamping Methods

In case of dispute, you will need to prove that you held the information before the alleged infringement. A computer file’s creation date is not sufficient proof (it can be modified). You need to establish a certain date.

The Soleau Envelope (INPI)

The best-known and most economical solution for SMEs and individual inventors.

Principle: You send a document in two identical copies to INPI (French Patent Office). One copy is kept by INPI, the other is returned to you with an official stamp certifying the date.

Cost: €15 for 5-year protection, renewable once (10 years maximum).

Advantages: Simplicity, low cost, established judicial recognition.

Limitations: Limited size (7 pages maximum per compartment), not suitable for frequent updates, no direct international validity.

Website: INPI – Soleau Envelope

Deposit with a Bailiff or Notary

Traditional solution offering maximum evidentiary weight under French law.

Principle: A ministerial officer certifies the content of a document on a given date and stores it.

Cost: Variable depending on volume, generally €100 to €500 for a simple deposit.

Advantages: Uncontestable evidentiary weight, universal acceptance by French courts, ability to deposit digital media.

Limitations: Higher cost, less agile procedure for frequent updates.

Blockchain Timestamping

Modern solution, particularly suited for tech companies and frequent updates.

Principle: A digital fingerprint (hash) of your document is recorded in a public blockchain (usually Bitcoin or Ethereum). This record is immutable and timestamped.

Cost: A few euros per timestamp via specialized services, or integratable into your internal processes.

Advantages: Automatable, suitable for software development pipelines (CI/CD), low marginal cost, traceability of each version.

Limitations: Judicial recognition still emerging in France (but growing), need to keep the original document corresponding to the hash.

Providers: Woleet, OriginStamp, KeeSign, or solutions integrated into document management platforms.

APP Deposit (Software)

For source code and software, the French Agency for Program Protection offers a specialized deposit service.

Principle: Secure deposit of source code with certain date, recognized as proof of prior possession.

Cost: From €120 excluding VAT for 5 years.

Website: APP – Agency for Program Protection

Evidence Methods Comparison Table

| Method |

Cost |

Evidentiary Weight |

Ideal for |

| Soleau Envelope |

€15 / 5 years |

★★★★☆ |

SMEs, inventors, stable documents |

| Bailiff / Notary |

€100-500 |

★★★★★ |

Strategic deposits, foreseeable disputes |

| Blockchain |

€1-10 / hash |

★★★☆☆ |

Tech, source code, multiple versions |

| APP Deposit |

€120 / 5 years |

★★★★☆ |

Software, source code |

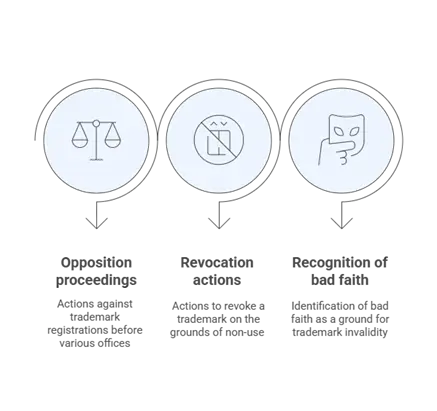

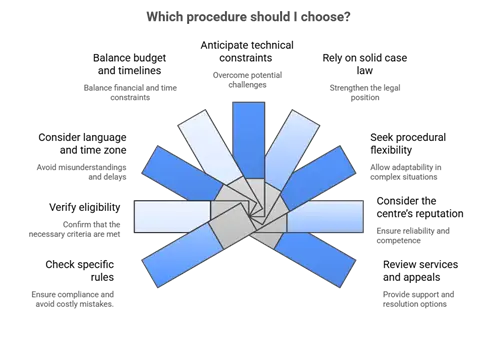

6. Taking Legal Action: Procedures, Timelines and Costs

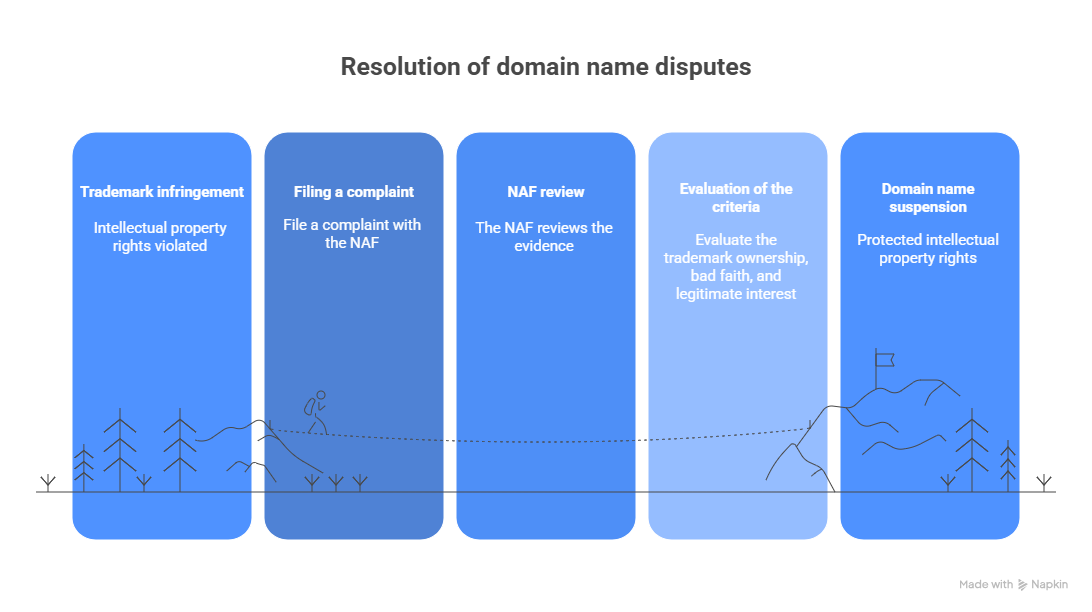

When a trade secret infringement is identified, several courses of action are available to the secret holder. The choice depends on urgency, severity of the infringement and objectives pursued.

Competent Jurisdiction

Civil Court (Tribunal judiciaire): competent for civil actions in trade secret matters. This is the general jurisdiction court.

Commercial Court (Tribunal de commerce): competent if the dispute is between two merchants or commercial companies and relates to commercial acts.

Labor Court (Conseil de prud’hommes): competent if the infringement is committed by an employee within the employment relationship (but action may be brought before the civil court for non-employment aspects).

Available Procedures

Interim Relief (Référé)

Fast-track procedure for obtaining provisional measures. Conditions: urgency and absence of serious dispute, or existence of imminent harm. Hearing timeline: generally 2 to 4 weeks after service. The judge can order provisional prohibition on use or disclosure of the secret, protective seizure of disputed products or documents, and penalty payments to ensure compliance.

Proceedings on the Merits

Full procedure for obtaining a definitive decision. Average duration: 12 to 24 months at first instance depending on complexity. Allows for final damages, permanent injunction and publication of the judgment.

Adapted Seizure-Infringement (Article L.152-3 of the Commercial Code)

Ex parte procedure (without the opposing party being notified) to establish an infringement and seize evidence. Application to the president of the civil court. Execution by bailiff at the presumed infringer’s premises. Sequestration of sensitive documents pending decision on their disclosure.

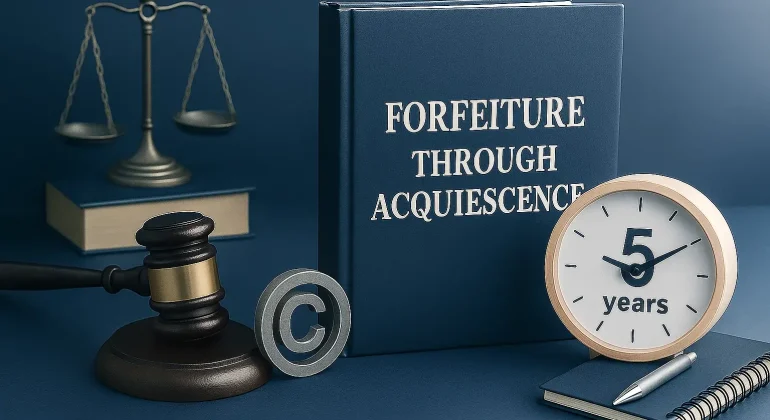

Limitation Period

Limitation Period: 5 Years

Civil action in trade secret matters is time-barred after 5 years from the day the trade secret holder knew or should have known the last fact enabling them to exercise their action (Article L.152-2 of the Commercial Code). This period can be interrupted by a formal notice or legal proceedings.

Cost Estimates

| Procedure |

Attorney Fees (estimate) |

Ancillary Costs |

| Formal Notice |

€500 – €1,500 |

— |

| Simple Interim Relief |

€3,000 – €8,000 |

Bailiff: €200-500 |

| Seizure-Infringement |

€5,000 – €15,000 |

Bailiff: €1,000-3,000 |

| Proceedings on Merits (1st instance) |

€10,000 – €50,000+ |

Court expert: variable |

These estimates are indicative and vary according to case complexity, firm reputation and geographic area.

Elements to Gather Before Taking Action

Before initiating proceedings, ensure you have the following elements:

Proof of prior possession: Soleau envelope, notarial deposit, blockchain timestamp.

Proof of protection measures: signed NDAs, IT charters, access logs, document classification.

Proof of infringement: disclosed documents, infringing products, witness statements, correspondence.

Damage assessment: loss of revenue, lost R&D investments, reputational harm.

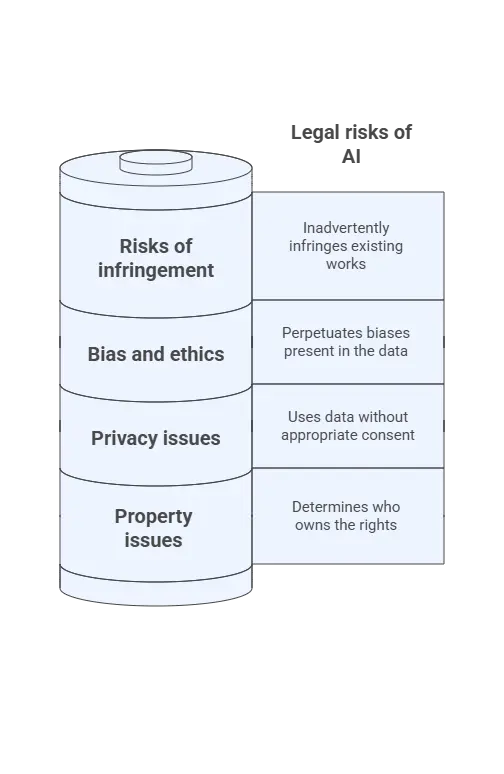

7. Remedies and Sanctions

In case of theft, misappropriation or unlawful disclosure, the law provides for extensive civil sanctions. Criminal liability remains limited to related offenses such as theft, breach of trust or receiving stolen goods.

What the Court Can Order

Prohibition orders: prohibition on using, manufacturing, marketing or disclosing the protected information. This prohibition may be accompanied by penalty payments for non-compliance.

Recall and destruction measures: product recall from the market, destruction of documents, files or products incorporating the secret (“infringing goods”).

Publication of the decision: at the infringer’s expense, in newspapers or on websites, to repair reputational harm.

Damages: calculated taking into account negative economic consequences (loss of earnings, lost opportunity), moral damage, and profits made by the infringer through the infringement.

Legal Exceptions (Article L.151-8 of the Commercial Code)

Trade secrets cannot be invoked in certain situations of overriding interest:

Exercise of the right to information: freedom of expression and freedom of the press, particularly to reveal information in the public interest.

Whistleblowers: disclosure of illegal activity or wrongdoing to protect the public interest (enhanced protection under the 2022 Waserman law).

Protection of a legitimate interest: particularly the right to evidence, subject to proportionality conditions established by 2025 case law.

Employee representatives: in the exercise of their functions (works council, union delegates).

8. Industry Case Studies

Trade secret protection is implemented differently across industries. Here are concrete examples illustrating the stakes and best practices.

Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Industry

Typical Case: Protection of Development Data

A laboratory develops a new molecule. Before filing a patent (which requires disclosure), all R&D data constitutes critical trade secrets: preclinical trial results, tested formulations, observed side effects, synthesis processes.

Issue: A leak could allow a competitor to file a “blocking” patent or develop a similar molecule.

Recommended specific measures:

Strict compartmentalization of R&D teams (each team only has access to their part of the project). Laboratory notebooks timestamped and signed daily. Enhanced NDAs with CROs (Contract Research Organizations). Clean room procedures for license negotiations.

Technology Sector (Startups, Software Publishers)

Typical Case: Protection of Algorithms and Source Code

A startup develops a recommendation algorithm that constitutes its competitive advantage. The source code and model training parameters are trade secrets.

Issue: A developer leaving for a competitor could recreate a similar solution.

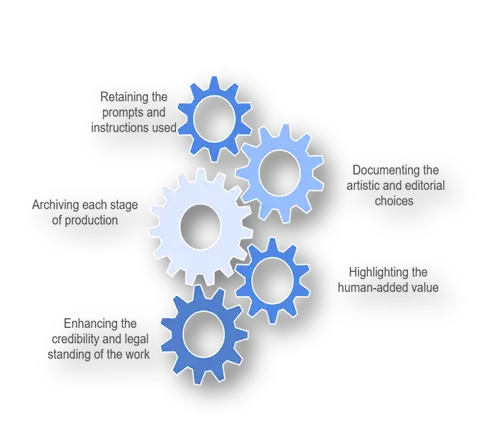

Recommended specific measures:

Technical architecture limiting access to complete code (microservices, module-based access). Systematic blockchain timestamping of commits. Specific confidentiality clauses in developer employment contracts. Monitoring of code repositories (GitHub, GitLab) to detect leaks. Formalized exit interviews with reminder of obligations.

Food and Beverage Industry

Typical Case: Protection of Recipes and Processes

A food manufacturer holds a unique recipe (sauce, beverage, processed product) whose secrecy is key to its market positioning. The most famous example is Coca-Cola, whose formula has been kept secret since 1886.

Issue: Disclosure would allow immediate copying by competitors or private labels.

Recommended specific measures:

Fragmentation of the recipe (different people know different parts). Coding of ingredients (internal codes instead of actual names). Restricted physical access to sensitive production areas. Regular audits of key ingredient suppliers.

Consulting and Professional Services

Typical Case: Protection of Methodologies and Client Data

A consulting firm develops proprietary methodologies and holds strategic data about its clients. These elements constitute major intangible assets.

Issue: A consultant leaving for a competitor takes their “address book” and methods.

Recommended specific measures:

Formal documentation of methodologies marked “trade secret”. Strict policy on use of client data (no export, anonymization). Client non-solicitation clauses. Team training on the distinction between personal skills and company assets.

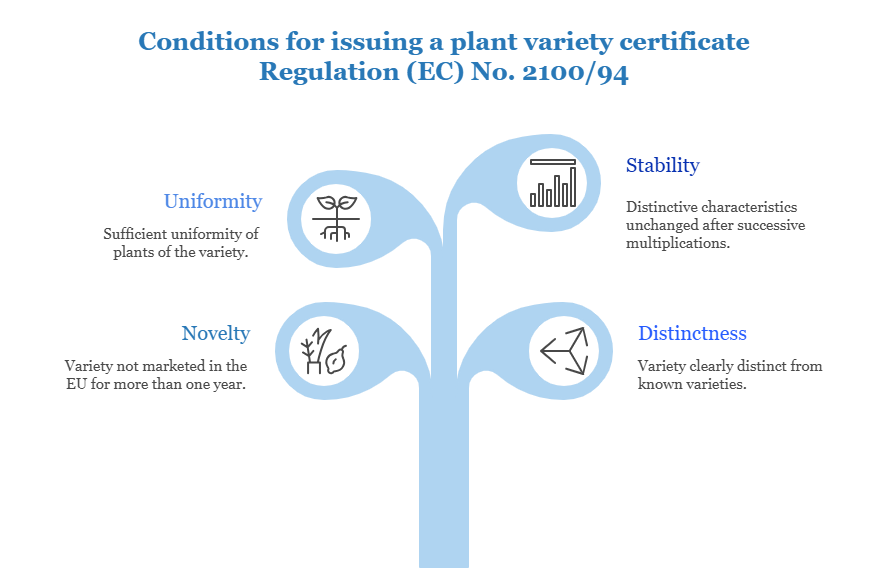

9. Coordination with Other IP Rights

Trade secrets are not intellectual property rights in the strict sense, but they interact with other available protections. An effective protection strategy often combines several regimes.

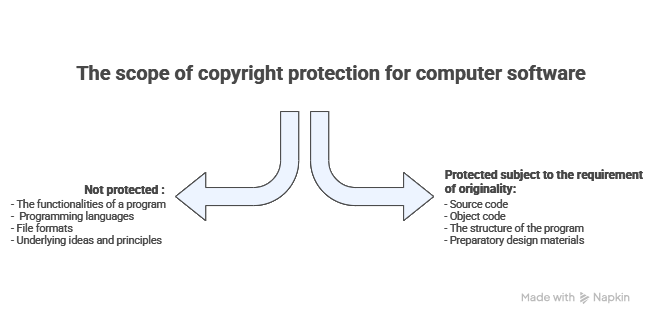

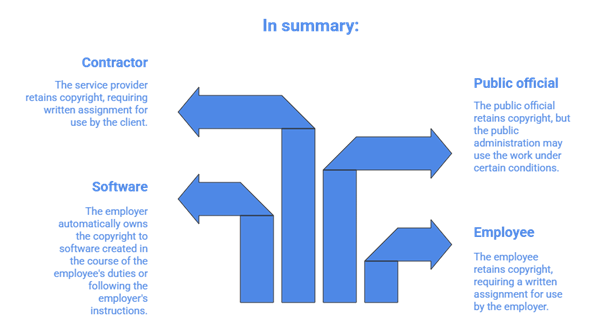

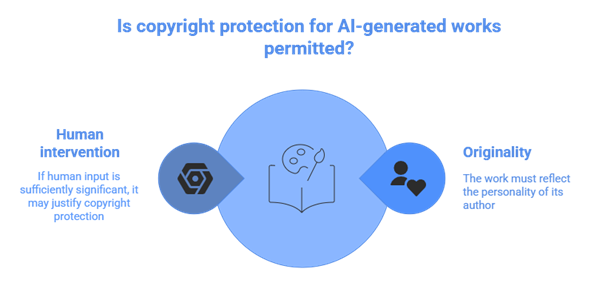

Trade Secrets and Copyright

Cumulation possible: Software source code can simultaneously benefit from copyright (which protects the original form of expression) and trade secret protection (which protects the underlying algorithms and business logic).

Key differences:

| Criterion |

Copyright |

Trade Secret |

| Formality |

None (automatic protection) |

Protection measures required |

| What is protected |

The original form |

The information itself |

| Duration |

70 years post mortem |

As long as secrecy is maintained |

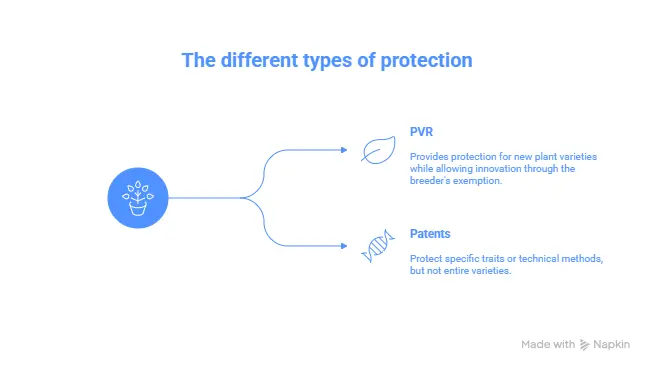

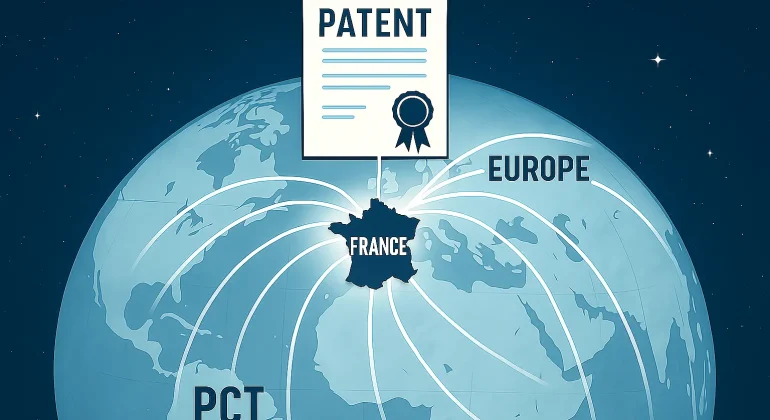

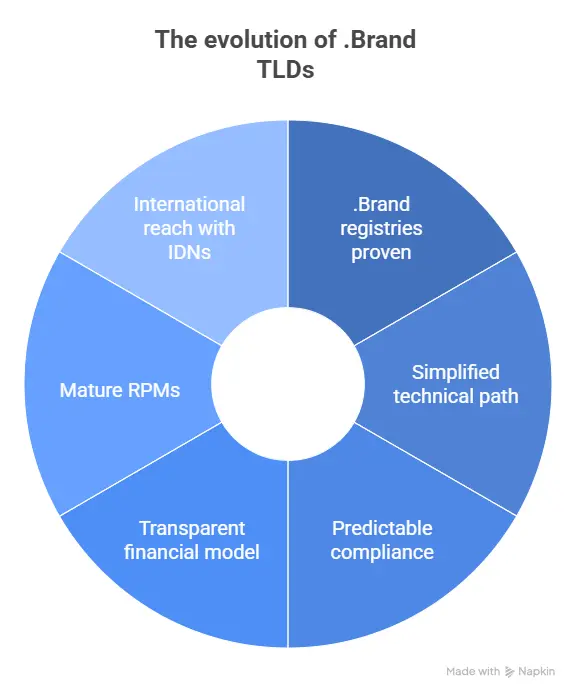

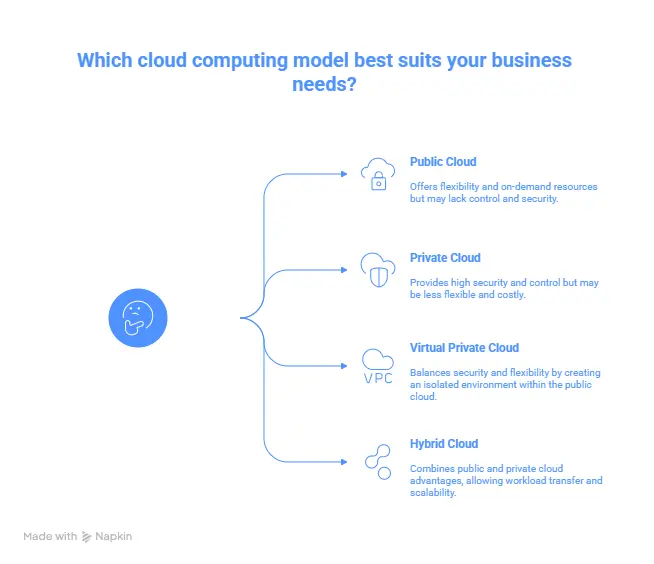

Trade Secrets and Patents

Strategic choice: To patent or keep secret? This choice is fundamental and irreversible.

Patenting is preferable when: The invention is easily identifiable through reverse engineering. You want to monetize the invention (licenses, assignments). The commercial lifespan is less than 20 years. You need a title enforceable against all (including independent discoverers).

Secrecy is preferable when: The information doesn’t meet patentability criteria. The secret can be maintained long-term (no reverse engineering possible). The commercial lifespan exceeds 20 years. You want to avoid patent costs and disclosure.

Warning: Patents Destroy Secrecy

Filing a patent requires publication of the invention (18 months after filing). This disclosure is definitive: if the patent is invalidated or expires, the information remains in the public domain. The secret is lost forever.

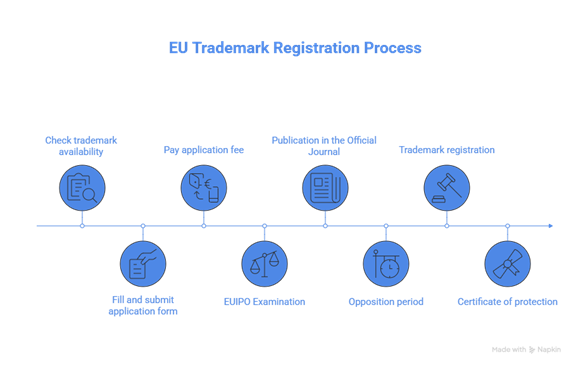

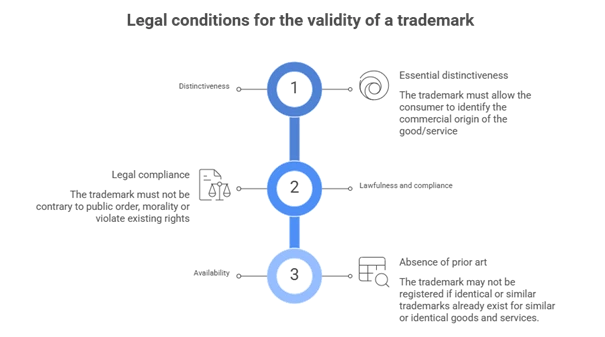

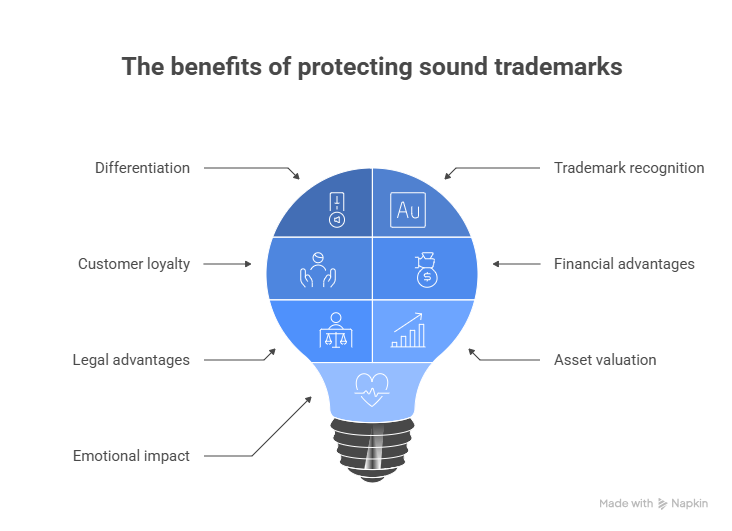

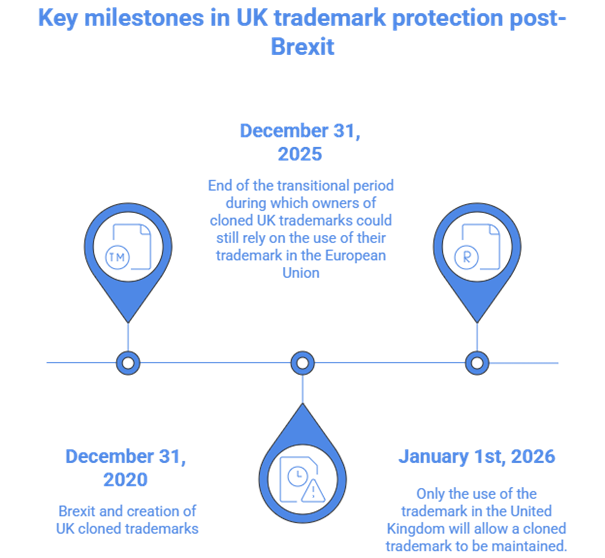

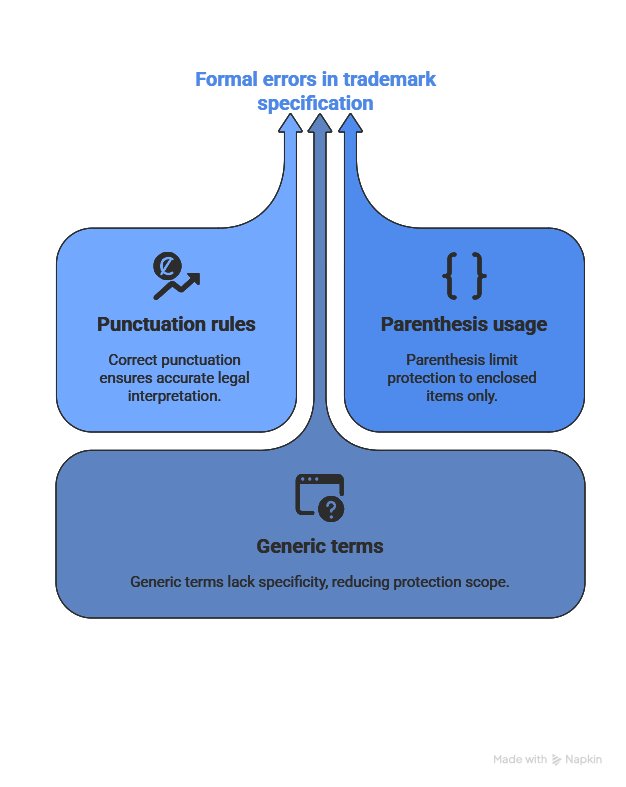

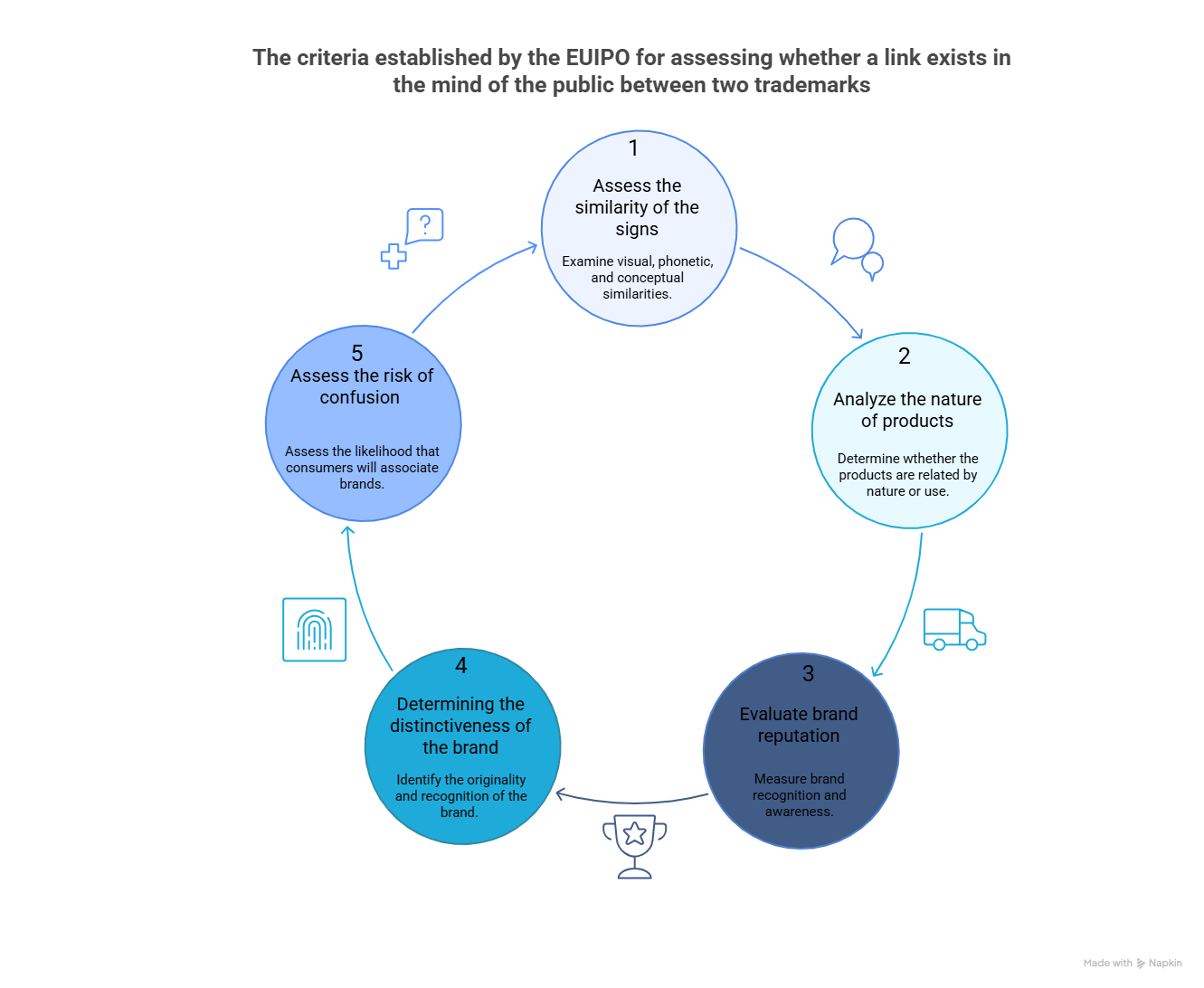

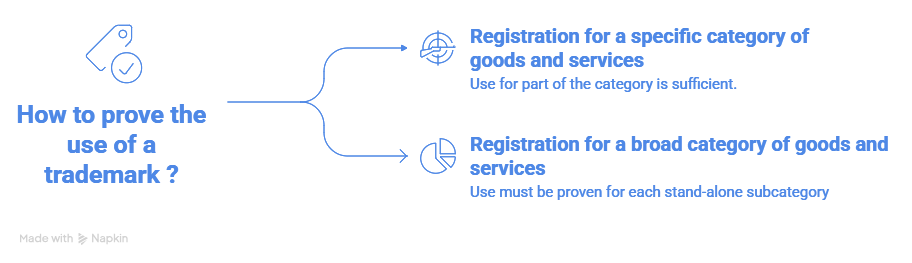

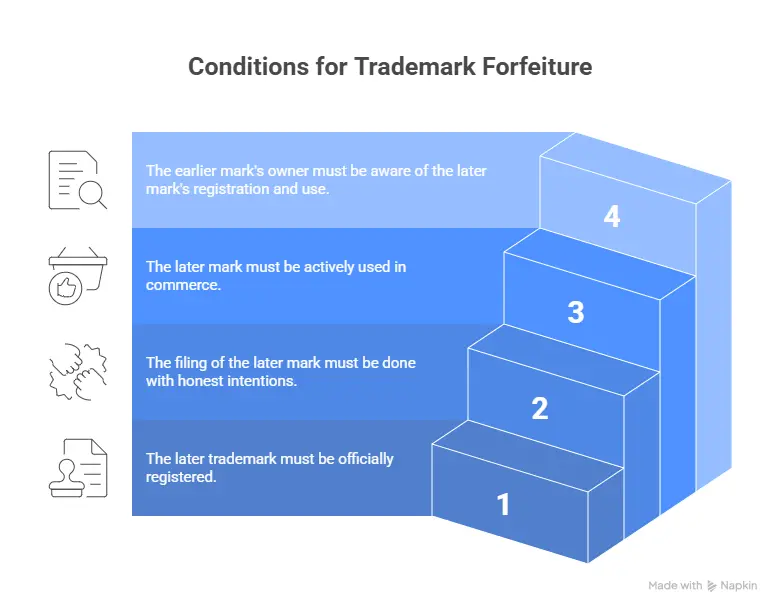

Trade Secrets and Trademarks

Coordination: Trademarks protect a distinctive sign (public by nature), while trade secrets can protect brand strategy, positioning studies, launch projects before public announcement.

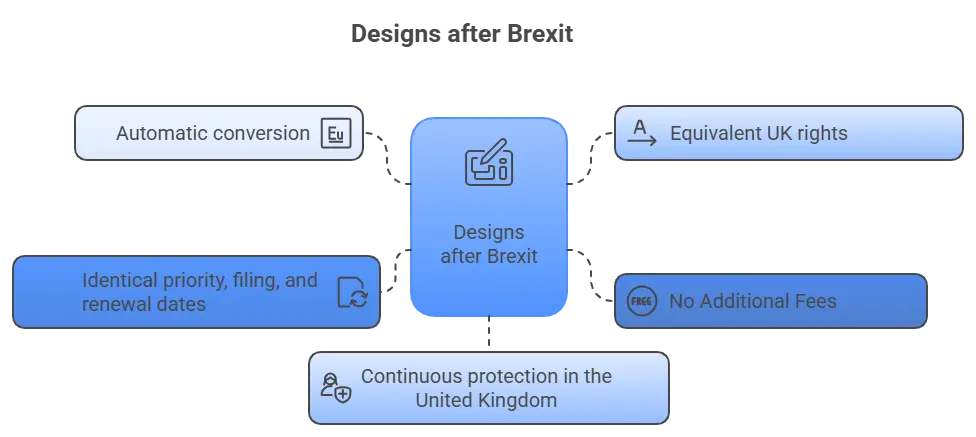

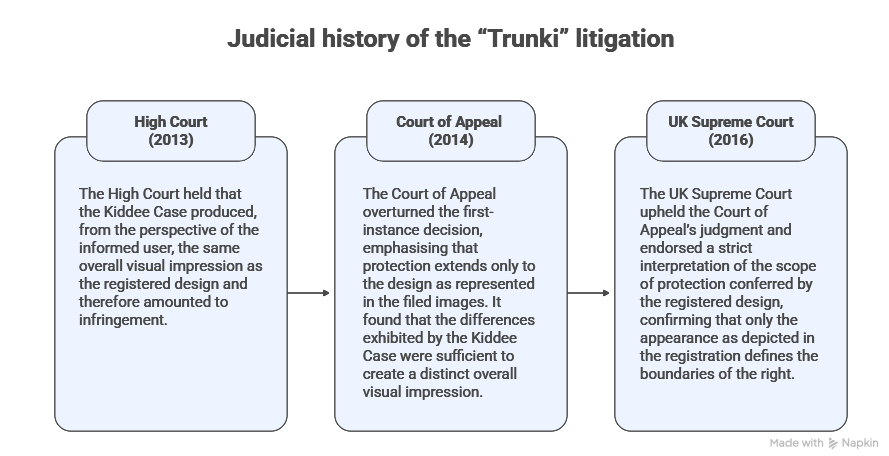

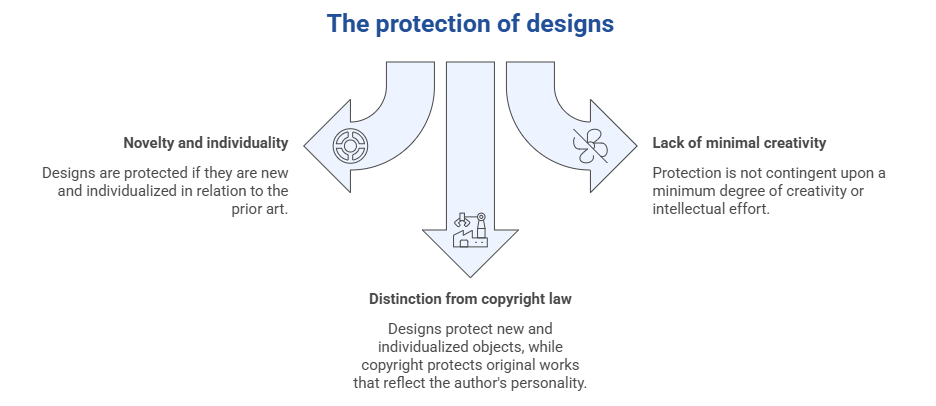

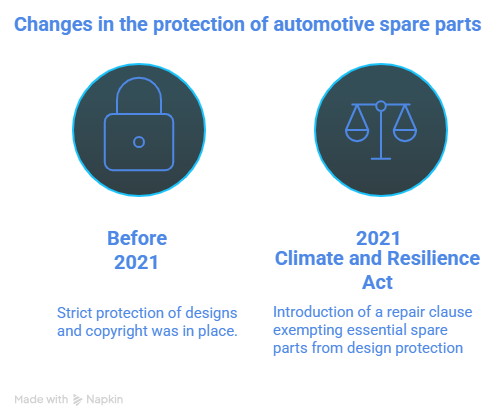

Trade Secrets and Designs

Coordination: Before launching a new design, plans and prototypes are trade secrets. Once the product is marketed, protection shifts to design rights (registered or unregistered for the EU).

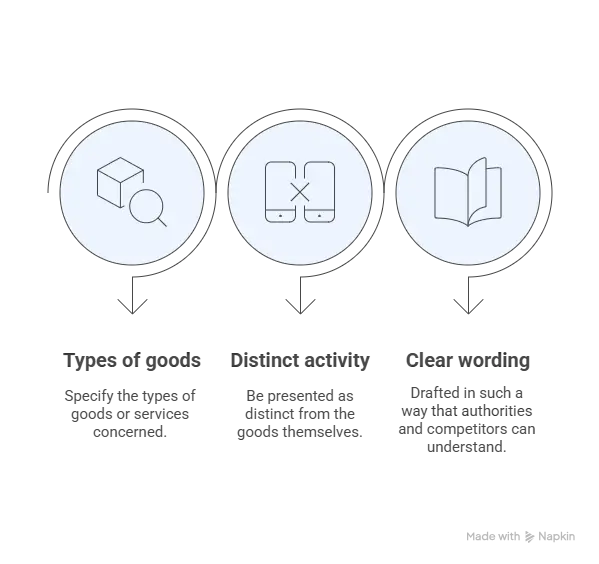

Trade Secrets and Know-How in Contracts

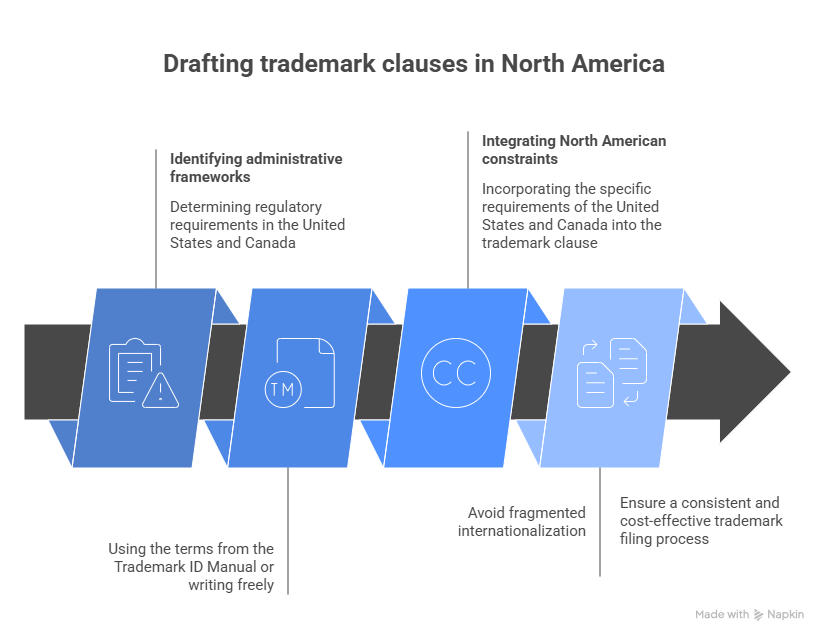

In know-how license agreements or franchises, trade secrets are often the basis of the transferred value. Confidentiality clauses must be particularly carefully drafted, with a precise definition of the know-how scope, protection obligations for the licensee, and control mechanisms.

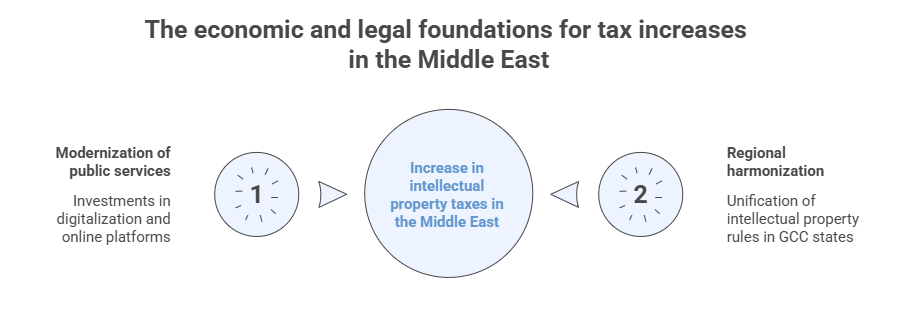

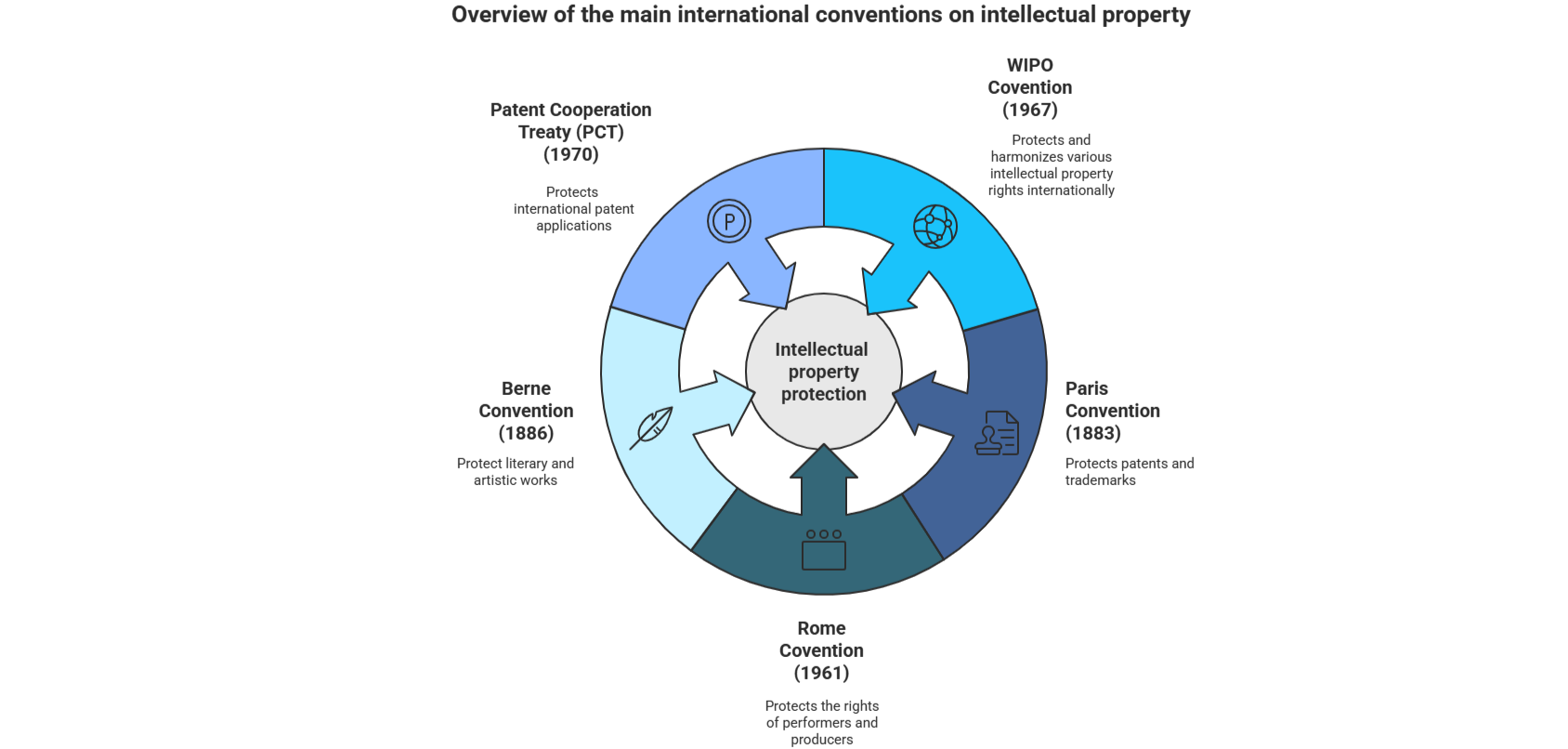

10. International Dimension

In a globalized economy, your trade secrets cross borders. Understanding the international protection framework is essential.

The Harmonized European Framework

EU Directive 2016/943 has harmonized protection across the 27 member states. This means the definition of trade secrets and available remedies are similar throughout the European Union, facilitating cross-border protection.

The TRIPS Agreement (WTO)

Article 39 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) requires the 164 WTO members to protect “undisclosed information”. This is the minimum ground of international protection.

International Comparison

| Jurisdiction |

Protection Level |

Particularities |

| United States |

★★★★★ |

Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA, 2016). Federal action available. Punitive damages up to 2x. Ex parte seizures. |

| European Union |

★★★★☆ |

Harmonized Directive 2016/943. Civil protection. No harmonized criminal component. |

| United Kingdom |

★★★★☆ |

Common law + directive transposition (retained post-Brexit). Breach of confidence. |

| China |

★★★☆☆ |

Revised Anti-Unfair Competition Law (2019). Improved protection but variable enforcement. |

| Japan |

★★★★☆ |

Unfair Competition Prevention Act. Criminal provisions. Effective protection. |

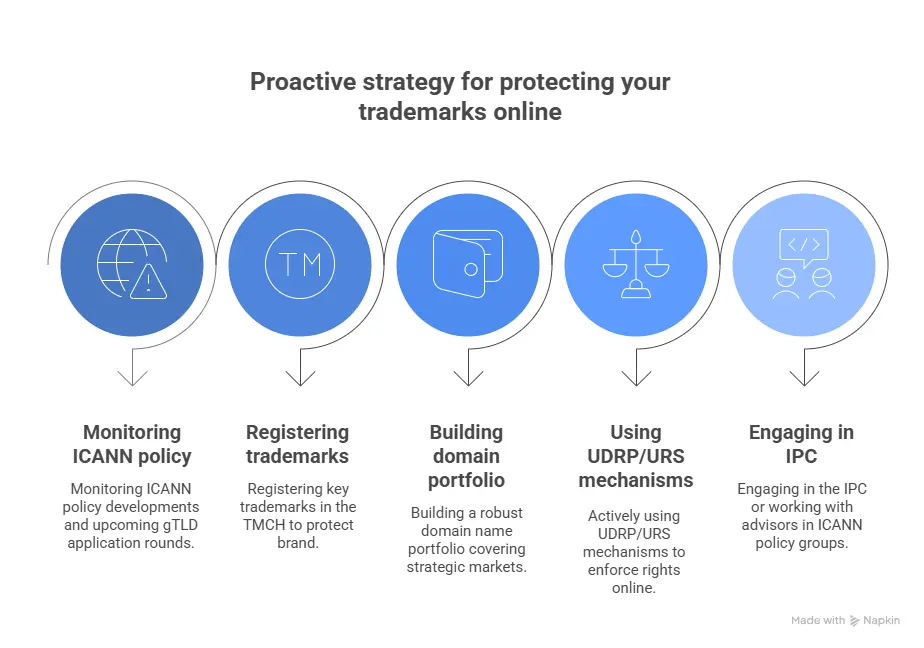

Best Practices for International Protection

Adapt your NDAs to applicable law: An NDA governed by French law won’t have the same effectiveness before an American or Chinese court. Include choice of law and jurisdiction clauses.

Map your information flows: Identify where your secrets transit (subsidiaries, subcontractors, cloud). Each jurisdiction crossed requires a protection analysis.

Strengthen clauses with foreign partners: In some countries with weaker protection, stricter contractual clauses (penalties, bank guarantees) can compensate.

Consider international arbitration: For cross-border disputes, arbitration (ICC, LCIA) can offer faster proceedings and facilitated enforcement in many countries (New York Convention).

11. Patent vs Trade Secret: Comparison Table

| Criterion |

Patent |

Trade Secret |

| Nature |

Public industrial property title |

Protection through confidentiality |

| Duration |

20 years maximum (with annuity payments) |

Unlimited as long as secrecy is maintained |

| Condition |

Public disclosure required |

Maintenance of secrecy required |

| Protection against |

All exploitation, including independent creation |

Unlawful acquisition only (not lawful reverse engineering) |

| Initial cost |

High (drafting, filing, examination: €5,000-15,000) |

Low (internal organizational measures) |

| Recurring cost |

Increasing annuities + international extensions |

Security measure maintenance |

| Main risk |

Design-around by different conception |

Leak or independent discovery |

| Monetization |

Easily monetizable (license, assignment, collateral) |

More complex monetization (due diligence required) |

| Ideal for |

Patentable technical inventions, monetization/licensing |

Know-how, commercial data, non-patentable information |

Combined Strategy

The two protections are not mutually exclusive. An optimal strategy can combine: patenting key innovations (strong, monetizable protection) and keeping complementary information secret (manufacturing processes, optimization parameters, implementation know-how).

12. Q&A: Your Questions About Trade Secrets

What is the difference between a patent and a trade secret?

A patent grants a 20-year monopoly in exchange for public disclosure of the invention. A trade secret protects information as long as it remains secret (unlimited duration), but does not protect against independent discovery by a competitor (lawful reverse engineering). A patent is enforceable against everyone; a trade secret only protects against unlawful acquisition.

Can an employee use their knowledge with a new employer?

Yes, acquired know-how (“experience”) belongs to the employee. The line is crossed if they take documents, client files or use specific technical secrets identified as confidential by their former employer. The distinction lies in the nature of the information: general skills (usable) vs. protected information (prohibited).

What constitutes a “reasonable protection measure”?

There is no official list, but case law recognizes: “Confidential” marking of documents, restricted computer access, signed confidentiality clauses, physical security of premises and staff training. Complete absence of such measures prevents legal protection. “Reasonable” is assessed according to company size and nature of the information.

Do trade secrets override whistleblower protections?

No. The law provides clear exceptions (Article L.151-8 of the Commercial Code). Trade secrets cannot be invoked to prevent disclosure of illegal activity or wrongdoing aimed at protecting the public interest (right to alert). The 2022 Waserman law strengthened this protection.

How long does protection last?

It is potentially perpetual. It lasts as long as the three conditions (secrecy, value, protection) are met. If the information becomes public — through disclosure, leak or independent discovery — protection is immediately and definitively lost. The example of Coca-Cola’s formula (kept secret since 1886) illustrates this potentially unlimited duration.

Can trade secrets yield to the right to evidence?

Yes, since the French Cour de cassation’s ruling of February 5, 2025 (No. 23-10.953). The judge must verify whether production of the document is “indispensable” to prove the alleged facts and whether the infringement of secrecy is “strictly proportionate” to the aim pursued. This is a case-by-case assessment that excludes exploratory requests.

Must I explain my algorithms to affected individuals?

Since the CJEU ruling of February 27, 2025 (C-203/22), yes for automated decisions with significant effects (scoring, profiling). You must provide “meaningful information about the logic involved” in an understandable manner. This doesn’t mean disclosing the complete algorithm, but explaining the criteria used and their influence on the decision.

What is the limitation period for legal action?

Civil action is time-barred after 5 years from the day the trade secret holder knew or should have known the last fact enabling them to exercise their action (Article L.152-2 of the Commercial Code). This period can be interrupted by a formal notice or legal proceedings.

How can I prove I held the information before the infringement?

Several methods establish a certain date: the Soleau envelope (INPI, €15 for 5 years), deposit with a bailiff or notary, blockchain timestamping, or APP deposit for software. A computer file’s creation date is not sufficient proof as it can be modified.

Can source code be protected by both copyright and trade secrets?

Yes, these two protections can be combined. Copyright protects the original form of the code (automatically, without formalities), while trade secret law protects the underlying algorithms and business logic (provided the 3 legal criteria are met and confidentiality is maintained).

Legal References

Need to Audit Your Protection or Take Legal Action?

Dreyfus assists you in implementing your protection measures, drafting your NDAs, timestamping your secrets and defending your interests in case of infringement.

Contact Our Experts

as an

as an

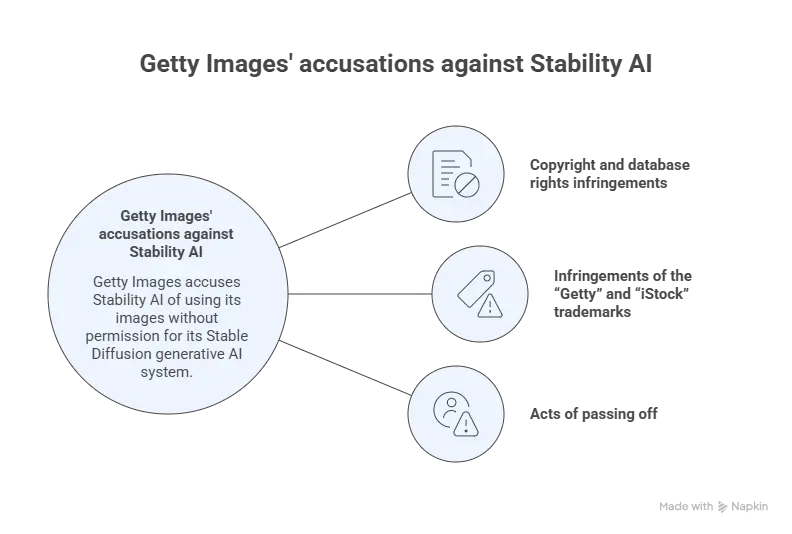

![Getty Images (US) Inc and Others v. Stability AI Ltd [2025] EWHC 38 (Ch) An interesting case in AI and Intellectual Property Law](https://www.dreyfus.fr/app/uploads/2025/02/Getty-Images-US-Inc-and-Others-v.-Stability-AI-Ltd-2025-EWHC-38-Ch-An-interesting-case-in-AI-and-Intellectual-Property-Law-770x420.webp)